Lands of Red and Gold #9: The First Speakers

The time of the Collapse was one of great panic and greater upheaval. Harvests failed, droughts persisted for years and stretched into decades, bushfires grew more frequent and spanned ever greater areas of the continent, and the arts of civilization seemed to be failing. In this time of chaos, people sought refuge in whatever consolation they could find.

In 842 BC, Robinvale, one of the old Wisdom Cities, was a place ripe for new ideas. Uprising and subsequent collapse had destroyed the great city of Murray Bridge, further downriver. In turn, this had ruined the arsenical bronze trade which supplied most of Robinvale's wealth. The seemingly endless drought had destroyed much of its agricultural hinterland. More than half of its former territory had already been abandoned, wattles and yams left to run wild while wetlands silted up and returned to semi-desert. Nomadic hunter-gatherers reoccupied the former farmlands, while the surviving farmers gathered in Robinvale itself, growing increasingly unruly.

Wunirugal son of Butjinong was one such farmer among thousands who arrived in Robinvale in that year. The exact location of his old farm is not known; at least two dozen sites would later be claimed to be the site of his birthplace. He is reliably known to have been a member of the Azure kitjigal, and he claimed the wedge-tailed eagle as his personal totem. Beyond that, nothing definite is known about his life before he arrived in Robinvale in the summer of 842 BC, although a thousand tales have since sprung up to explain how he spent his early years.

Just as with his early life, what Wunirugal accomplished in Robinvale in that year has been recorded in many contradictory versions. Certainly, Wunirugal was among the more vocal of the farmers complaining about the lack of food, to the point where the city militia took official notice of him. Some say that he spoke so eloquently that the militia agreed to escort him before the Council to plead his case. Some say that Wunirugal outran the militia and entered the Council hall on his own. Some say that he was struck immobile by a vision and was carried bodily into the Council hall for investigation. One account claims that the Council came out to meet him in the main square of Robinvale, but that version is usually discounted.

No two versions of Wunirugal's meeting with the Robinvale Council agree on what he said, or even on the names of the members of the Council. There is surprising unanimity about the Council's decision: Wunirugal was deemed a danger to public order, ordered to be expelled from Robinvale immediately, and not to return for a year and a day, on pain of death. Wunirugal left, but he was not silent along the way. Again, the accounts of his words vary, but all sources agree that he persuaded at least three hundred people to come with him into exile.

Wunirugal led his new followers far from Robinvale. Accounts of their journey include some fantastic events. The most nearly-universal of those events is an account of how soon after he left the city, Wunirugal received another vision. While having this vision, he was struck by lightning which came from clouds which produced no rain, yet he survived with no ill effects. Scholars will long argue whether this widely-reported event is factual. It might be; some lightning strikes from thunderclouds where rain is falling but evaporates before it reaches the ground, and some people do survive lightning strikes. Certainly, the reports of what Wunirugal did after the lightning strike are in surprising agreement. He is said to have fallen to his knees and said: "Help me, help me. Tell me what I should do, O lightning blue?"

Whatever the merits of this account, it is clear from the many tales of Wunirugal that he had visions, or what other people believed to be visions. He drew on these for guidance, and led his followers up the Murrumbidgee. This river is one of the major tributaries of the Murray, but it had been a relative backwater since most of the trade flowed up and down the main river. Wunirugal led his followers past a long series of natural wetlands, and reached an area of lush, fertile soils which flourished even in the drought. He declared that this would be the perfect place to build a town. According to most (but not all) accounts, he said, "Here, the earth will always grow. Here, we can build a city which will have no rival."

He called the new city Garrkimang.

--

Garrkimang [Narrandera, New South Wales] grew to become one of the four great cities of the Classical Gunnagal. Like their contemporaries, the people of Garrkimang could trace their ancestry back to their Formative forefathers. However, Garrkimang developed along a different path from its neighbours. In language, it was much more distinct than any of the other Classical cities. The migrants who founded Garrkimang were a combination of refugees from the former Murray Bridge and the most westerly areas of former Robinvale territory. This meant that their speech had diverged much further; while there were clear underlying similarities with other Gunnagalic languages, learning the speech of Garrkimang was considerably more difficult for foreigners than that of any other Classical city.

In culture and religion, Garrkimang was also unlike any other Classical city. The inhabitants called themselves the Biral, a name which means roughly "chosen ones." They traced this back to the migration under Wunirugal, believing that they had been chosen to be granted their new land as a sacred trust. Their religion had a similar foundation to the older Gunnagal beliefs; they still shared the same general view of the Evertime and of the spirit-beings who inhabit eternity, although they gave different names and attributes to many of those beings. Yet the old beliefs had been overlaid by a new religious structure, that of the First Speakers and their representatives who interpreted the world.

The heirs of Wunirugal ruled Garrkimang as absolute monarchs. The old cities had been ruled by oligarchic councils, but there had never been such an institution in Garrkimang. The rulers claimed the title of First Speaker, and based their rule on religious authority. They asserted that they were entitled to rule because they possessed the talent of interpreting the wisdom of eternity. They proclaimed their rule through a series of law codes first promulgated in Garrkimang itself, and which were spread throughout every city and town which came under their rule. They also adopted a set of protocols in terms of conduct, dress, and ceremonies to support the view of the First Speaker as the greatest moral authority. This was most obviously shown in the privilege which gave the First Speaker his title: in any meeting or ceremony, the First Speaker always was the first person to speak. Anyone who dared to speak to the First Speaker unless directly addressed first would be fortunate if they were simply exiled; death was a common punishment for such a social faux pas.

The First Speakers were not always direct heirs of Wunirugal; the succession was open to all males in the royal family. It was even possible, although difficult, for those not of direct royal descent to be accepted into the House of the Eagle; adoption was an accepted method for particularly eminent people to join the royal family and become eligible for the throne. The succession was often decided by the will of the First Speaker, who would designate an heir from amongst his relatives. On some occasions, the royal princes would meet to acclaim an heir when the succession was unclear. Public disputes over the succession were rare, and civil wars over succession would be unknown until the declining days of the monarchy. Incompetent rulers could, however, be removed. If the royal family thought that a First Speaker was very bad at listening to the wisdom of eternity, then that First Speaker would be quietly offered an opportunity to commune with eternity more directly, and another member of the royal family would take the throne.

Despite some internecine intrigues in the House of the Eagle, Garrkimang's monarchs were always much more secure on their thrones than the rulers of any other Classical city. The royal family had the bastion of religious authority to support their rule. More than that, the old kitjigal system had broken down during the time of the Great Migrations. With so many people displaced, two of the eight kitjigal were lost entirely, and the rest were abandoned as social institutions. In the other Classical cities, the kitjigal evolved into armed factions which preserved their own privileges, including the right to form social militia. Monarchs in Tjibarr, Weenaratta and Gundabingee always feared uprisings amongst the factions, but Garrkimang did not have this threat.

Some aspects of the kitjigal were still preserved in Garrkimang, but in much-changed form. From its founding, Garrkimang's armies were traditionally divided into six warrior societies, each of which had their own initiation rites, values, informal social hierarchies, and special duties. These societies were named the Kangaroos, the Corellas, the Ravens, the Kookaburras, the Echidnas, and the Possums. Each of these societies derived their names and some of their values and practices from the old colours and social codes of the kitjigal [1]. Garrkimang also had six trading associations, each of which emerged from the old kitjigal colours. These formed into a system of recognised partnership and profit-sharing, and were in effect early corporations which had collective ownership of farming land, mines, trading caravans, and other ventures, who shared the profits and risks amongst all members of their society. The trading societies were powerful voices within Garrkimang and its dominions, but since all military and religious power was reserved for the monarchy, the trading societies never acquired the same political power which the factions did elsewhere.

--

Garrkimang occupied what was probably the best agricultural site of any Classical city. It had the convenience of large areas of productive land upriver suitable for the Gunnagalic system of dryland agriculture, and a series of natural lagoons and other wetlands downriver which were easily expanded into the managed artificial wetlands which the Gunnagal so favoured. The wetlands downriver of Garrkimang were productive enough that the First Speakers encouraged the diversion of some water to irrigate a few chosen crops, unlike the usual Gunnagal farming system which relied on rainfall. This irrigation was mostly for their favoured drug, kunduri, but also for the cultivation of a few fruits and other high-status foods [2].

With productive lands as the foundation of their power, the First Speakers turned Garrkimang into the capital of a large kingdom which controlled three significant rivers, the Murrumbidgee, the Lachlan, and the Macquarie. They controlled almost all of these rivers, except for the farthest downstream areas of the Murrumbidgee and the Lachlan, which were under the control of the kingdom of Tjibarr. By edict of the First Speaker, in 256 AD the kingdom became known as Gulibaga, the Dominion of the Three Rivers.

While Gulibaga was a powerful kingdom, for most of the Classical era it was only one nation amongst four. The three Murray kingdoms of Tjibarr, Weenaratta, and Gundabingee all flourished during this era. The four nations each had a vested interest in ensuring that none of their rivals grew too powerful, which was reflected in a fluid system of alliances that prevented one kingdom from completely defeating any of the other four.

The alliance system broke down in the Late Classical period, thanks to the social disruptions of the first blue-sleep epidemics in the mid-fourth century AD, and a more than usually faction-ridden aftermath in the kingdom of Tjibarr. This let the First Speakers extend their control to the River Darling, a major tributary of the Murray, and the key transport route for tin from the northern mines. Gulibaga kept its control over the tin trade from this time, despite efforts to dislodge its forces. While tin was still traded further downriver to the other Classical kingdoms, Gulibaga received the largest share, and from then on they had better access to bronze than their rivals.

It was an advantage they would put to good use.

--

In the vanished era of the Classical Gunnagal's ancestors, war was as much a series of raids for honour as it was a contest between nations. The era of the Collapse changed that; wars were now fought for national gains. Still, while Classical military tactics were more organised than those of their ancestors, they were not particularly advanced. The archetypal Classical warrior carried a wooden shield and a bronze-tipped spear, sometimes also with a short sword. Armour was rare, save perhaps an emu leather helmet. Captains might have more bronze armour, but the common Classical soldier was only lightly-protected. Battle tactics and training were not particularly advanced; being a soldier was a part-time occupation for most people, and while the Classical Gunnagal knew how to form a line of battle, their coordination and discipline were both limited.

With a near-monopoly on bronze, Gulibaga's warriors changed the old pattern. The kingdom had the wealth and the resources to equip their leading warriors with better armour, typically a bronze helmet and greaves, and hardened leather breastplates. They could afford to maintain the first large professional standing army, elite units who trained and deployed together. They standardised and extended their tactics with a number of military innovations. Professional Gulibagan warriors carried pikes and rounded shields, transforming them into Australia's first heavy infantry, who could break almost any enemy line of battle. In battle, the core infantry were supported by lightly-armed skirmishers who used bows with stone or bone-tipped arrows, and who helped to disrupt enemy formations.

By the mid fifth century AD, Gulibaga's military organisation was clearly superior to anything developed by its Classical rivals. The combination of better arms, armour and tactics would prove almost irresistible.

--

With its superior military organisation and resources, Gulibaga transformed itself from a kingdom into an empire. In the name of the First Speakers, its armies waged war on its classical rivals, particularly its most powerful opponent, the kingdom of Tjibarr. In a series of campaigns from 467 AD to 482 AD, Gulibagan armies conquered most of Tjibarr's territory, although the city walls withstood siege after siege. In 486-488 AD, a long siege finally broke through the walls of Australia's most ancient city.

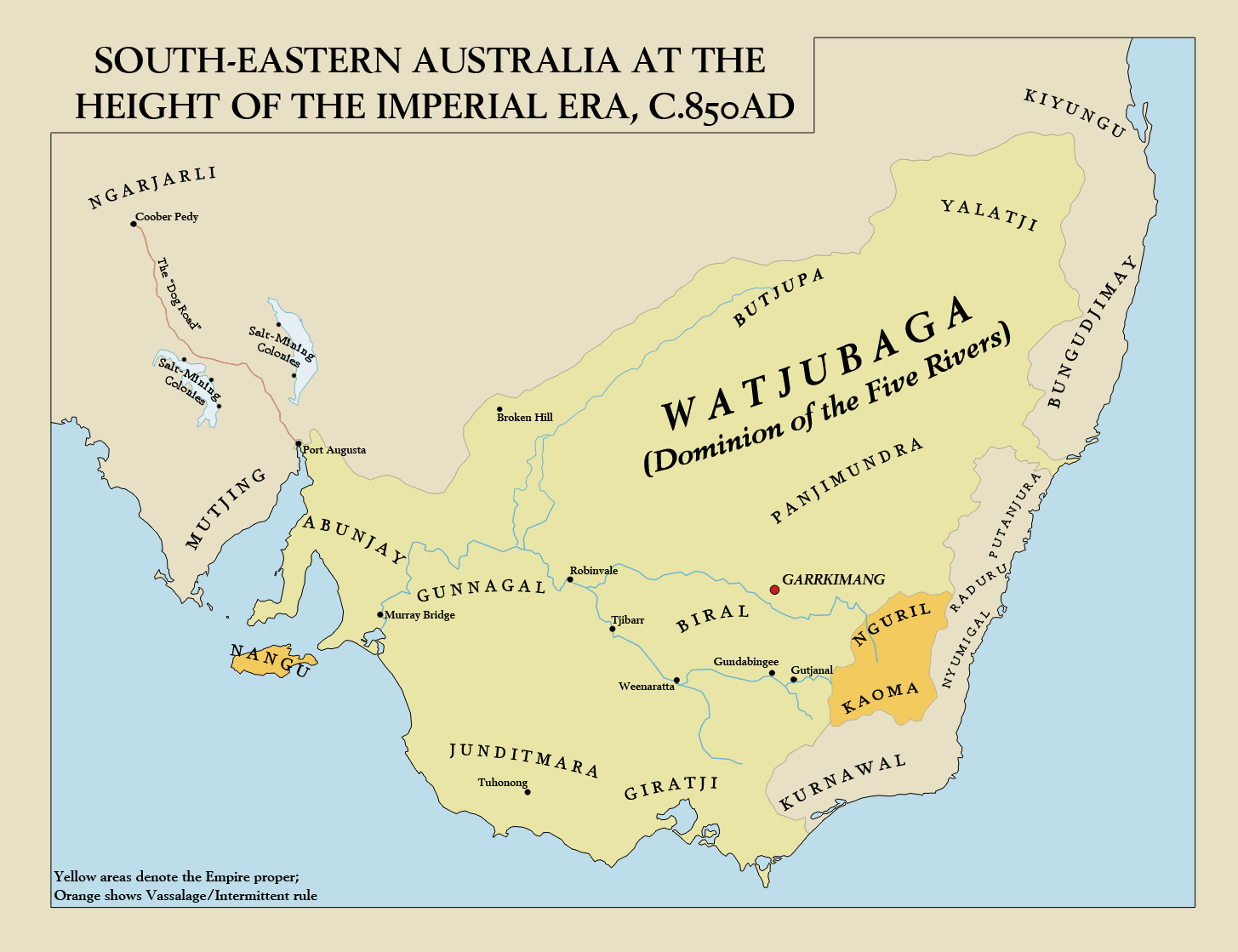

In previous wars between Classical kingdoms, similar victories had seen defeated monarchs being reduced to effective vassals, with "advisors" from the victorious kingdoms dictating policy. Such advisors were usually thrown out within a few years, with the support of one of the other four kingdoms. With the defeat of Tjibarr in 488, however, the First Speakers did something unprecedented: they deposed the old monarchs and created a new province with an appointed governor. This action is usually taken to be the start of the Imperial era in the history of the Murray basin. Some authorities use a later date of 556 AD, when Gulibagan armies subdued the forces of Gundabingee, the last surviving Gunnagal kingdom. After this victory, the First Speaker renamed his nation to Watjubaga, the Dominion of the Five Rivers [3]. This would be the name by which it would be remembered.

With the resources of the Five Rivers at its command, Watjubaga expanded into Australia's first and largest indigenous empire. Its core territory remained the old Gunnagal lands along the Murray and Murrumbidgee, but its armies carried its rule to most of the agricultural regions of south-eastern Australia. In the north, one of its major early accomplishments was the gradual expansion along the Darling until they conquered the New England highlands directly, taking over the sources of tin and gems. To the south, they faced some determined resistance from the Junditmara peoples, who had their own developing kingdoms and a hierarchical social code based on duty to one's elders, conformity, and rewarding loyalty. Still, the might of professional discipline and imperial bronze saw the Junditmara kingdoms defeated one by one.

--

At its height around 850 AD, Watjubaga claimed suzerainty over territory which stretched from the Darling Downs in the north to Bass Strait in the south, and to the deserts and the Spencer Gulf in the west. These northern and western borders represented what amounted to its natural frontiers. In the north, the Darling Downs were inhabited by a set of feuding Gunnagalic peoples who dwelt in small villages and raided each other for emus and honour. Their northern limits were bounded by the growth of the red yam, which does not grow properly in the tropics. The Empire imposed its authority on these peoples, although the distance and the fractious nature of its subjects meant that its authority was perforce rather loose.

Likewise, the western and southern borders of the Empire were largely bound by desert and the seas. Watjubaga controlled all of the thinly-inhabited lands west of the Darling River, and the more fertile lands further south around the Murray Mouth, the Spencer Gulf, and along Bass Strait. They largely ignored the Eyre Peninsula, a small, lightly-settled agricultural land beyond the Spencer Gulf, since they deemed it too poor and too difficult to control without decent sailing technology. Direct imperial control did not always end with the desert; imperial forces maintained a few inland colonies to access some key resources such as the silver, zinc and lead of Broken Hill, and a few salt and gypsum harvesting colonies on some of the dry inland lakes.

In the inland regions of Australia, imperial influence was minimal, although they did have some contact with the desert peoples. Ancient trade routes stretched across much of the outback; ancient traders had travelled hundreds of kilometres across some desert routes when trading for flints and ochre. With the establishment of imperial outposts along the desert fringes, some of these trade routes were expanded. In a few locations with particularly high-value resources, the local hunter-gatherers found that they could mine a few key goods and trade these for food and metal tools from the agricultural peoples along the coast.

The most important of these routes became known as the Dog Road, which started at the imperial outpost of Port Augusta and ran over five hundred kilometres northwest to Coober Pedy. Here, the local Ngarjarli people mined opals from one of the richest sources in the world. The climate was far too dry to support a large population, or even a permanent population, but like most hunter-gatherer societies, the Ngarjali had a lot of under-used labour.

Thanks to the imperial interest in opals, the Ngarjali found a reason to mine those gems and establish a semi-permanent settlement at Coober Pedy, where some of their people slowly mined opals throughout the year. Once a year, in June when the heat was least severe, the annual trading caravan set out from Port Augusta. People and dogs pulled travois loaded with trade goods: clay vessels full of wattle-seeds, smoked meats, dried fruits, and ganyu (yam wine); metal tools; textiles such as clothing, baskets and bags; and kunduri (chewing tobacco). When they reached Coober Pedy, they held a great celebration and trading fair with the Ngarjali, and exchanged opals for their trade goods. This reliable food storage allowed the Ngarjali to occupy the same area for a large part of the year, although water shortages meant that they sometimes needed to move elsewhere.

--

While Watjubaga had clearly-defined natural borders in the north, west and south, its eastern frontier was more ambiguous. In most regions, imperial authority ran as far as the Great Dividing Range; the combination of rugged terrain, lack of beasts of burden, and distance from the imperial heartland meant that conquering the backward peoples of the eastern seaboard was usually not deemed to be worth the effort. In central Victoria, however, imperial armies had marched east from Junditmara lands and gained control of the lands around Port Philip Bay and West Gippsland. In the headwaters of the Murrumbidgee, the Monaro plateau was occupied by sullen imperial subjects who sometimes paid tribute and often rebelled. Further north, the rich farmlands of the Hunter Valley were inhabited by city-states who were reluctant imperial tributaries; this was the only region where imperial influence extended to the Tasman Sea. Apart from the Hunter, the eastern seaboard of Australia was independent of imperial control.

As an empire, Watjubaga thus claimed immense territory, but in many cases its level of control was limited. The empire maintained its predominance through its military strength, and more specifically through a core of well-equipped veteran soldiers who were the battlefield heavyweights of their day. In a land without cavalry, the imperial heavy infantry could be relied on to shatter any opposing army in any battle on open ground. Still, rebels often found ways to neutralise these tactics, particularly when fighting on irregular ground or resorting to raids and retreating to rugged terrain where the heavily-armoured imperial infantry had difficulty pursuing them.

Moreover, imperial manpower was limited. Watjubaga drew its soldiers exclusively from the ethnic Biral, who mostly dwelt in the ancient territories around Garrkimang, formed a significant minority in the rest of the Five Rivers, and elsewhere were either a small ruling elite or inhabited a few colonies established both as garrisons and trading posts. Joining the Biral was difficult for anyone of a foreign ethnicity; marrying in sometimes happened, but otherwise the only way to join was to persuade a Biral family to formally adopt someone, which was rare. These limitations on imperial manpower became an increasing strain with the large territories where Watjubaga tried to maintain its rule. The large distances and slow transportation technology meant that when away from one of the major rivers, even the local Biral elite often partially assimilated into the local culture, and the long lines of communication meant that local garrisons in distant territories were perpetually vulnerable to revolt.

--

At its height, Watjubaga ruled over vast territories, but it did not create much of a sense of unity amongst its subjects. With the Biral forming an elite ruling class, the subject peoples were not particularly inclined to adopt Biral language or culture. Some people learned Biral as a second language, since it was the language of government, but it did not become the primary language of any but the Biral themselves.

Still, while relatively few people could speak or write the Biral language, an increasing number of people in the Empire were literate. Later archaeologists would be aware of this by the wealth of written information preserved in clay tablets. Written accounts preserved considerable details about life within the empire, recorded in government records, legal documents and other archives, but also through an abundance of private documents such as letters, trade records, and religious texts. Within most regions of the Empire, government administrators could simply place tablets announcing new proclamations or other news in town squares, and be confident that they would be read, understood, and the information conveyed to everyone in the city.

The nature of imperial rule varied considerably amongst the imperial regions. Watjubaga's core territories were the heavily-populated areas along the Murray and Murrumbidgee, and the almost as heavily-populated area around the Murray Mouth and along the Spencer Gulf. Here, imperial administrators exercised considerable control over everyday life, using a system of labour drafts which required every inhabitant to perform a certain number of days service for the government every year. This labour was required outside of the core harvest times, and was used to construct and repair public and religious buildings, maintain artificial wetlands, and sometimes to grow high-value crops such as corkwood (the key ingredient of kunduri), which were subject to imperial monopoly.

Outside of the core territories, the labour draft system was much less prevalent. The imperial government tried to enforce it amongst the Junditmara in the south, with only limited success; this was one reason for the repeated revolts in that region. In the more thinly-inhabited regions along most of the Upper Darling, power was usually delegated to local chieftains instead. In the New England tablelands, the Empire ran the mines using a system of labour drafts, but otherwise imperial control there was limited. In most other regions, the Empire did not even attempt to directly rule the territories, but simply collected tribute from local leaders.

In terms of religion, Watjubaga likewise exercised only limited control over the views of its subjects. The imperial view of religion was syncretic; like all of the Gunnagalic religions shaped during the Great Migrations, it had assimilated some indigenous beliefs from the hunter-gatherers displaced during the population movements. The underlying structure of their religion remained similar to their ancestors; they viewed the present world as only one aspect of the Evertime, the eternity which controlled everything and was everything.

Within this framework, the actions of individual heroes, sacred places, and of spiritual beings were all adopted in a cheerful mishmash of beliefs. The Empire had no qualms about recognising other religious traditions as simply being aspects of the same underlying truth. Their only concern was for the religious role of the First Speakers, who had always maintained the claim that they were best suited to interpret the wisdom of eternity. Obedience to imperial authority was treated as accepting this religious duty; civil disobedience or outright rebellion were both treated as blasphemy. Beyond that, what individuals or peoples believed was of no concern to the imperial administration.

--

The Imperial era spanned several centuries, and it brought immense wealth to the royal city of Garrkimang. Extensive use of labour drafts usually meant that much of this wealth was invested into public architecture. The First Speakers and other noble classes amongst the Biral had a fondness for large, ornate buildings. At the height of imperial rule in 850 AD, Garrkimang had five separate palaces reserved for the royal family, and three dozen smaller palaces used by other noble families. They also built several large temples and many smaller shrines dedicated to various spiritual beings or former First Speakers. The royal city also held several large amphitheatres used for sporting and religious events.

Imperial engineering techniques were not particularly advanced by Old World standards, although they had developed considerably from their Classical ancestors. Imperial engineers built very effectively using a wide variety of stones. They had not discovered the arch, and lacked both the wheel and beasts of burden to help with moving building material around, but they had waterborne transport and lots of determination. Imperial construction techniques tended toward large, solid stone buildings, with the walls supported by buttresses at key points. They could build some very large columns, but they mostly used them for freestanding monuments or as aesthetic elements of building design, rather than as the main structural support. In the most elaborate imperial buildings, the solid buttressed walls were overhung with large eaves, and the eaves themselves were supported with elaborately-carved columns.

Imperial aesthetics placed great value on elaborate displays in architecture. This meant that imperial buildings were covered both within and without by a great many decorative elements: intricate ornamental stonework, sculptures, glazed tiles, murals, and above all bright, bright colours. Some valued stones were transported large distances because their appearance was preferred; the marble quarries at Bathurst and Orange were far from Garrkimang, but that was of little concern to the imperial engineers who ordered large quantities of marble to decorate the exterior of the palaces and temples. Colour was an integral part of most decorations, from some coloured stones, or glazed tiles, or from a variety of paints. While the individual stylistic elements were wholly alien to European building traditions, the overall impression of imperial architectural styles would be reminiscent of the Baroque period. In technicolour.

--

In technology, the advent of the Imperial era did not mark any dramatic improvement over the preceding Classical era. While the First Speakers were not hostile to new learning, the focus of imperial efforts was on administration, aesthetic improvements, and organisation, rather than any particular sense of innovation. Outside of engineering, architecture, and military technology, there were no fields where the First Speakers would be particularly interested in supporting experimentation or the application of new ideas.

Still, the spread of literacy allowed more communication of ideas, as did the growth of trade under the imperial peace. This contributed to some technological advances during the Imperial era. Metallurgy became considerably more advanced during this period, particularly in the development of many copper-based alloys. The exploration of the Broken Hill ore fields led to the isolation of zinc ores, and these were used to create brass. With imperial aesthetics being what they were, most brass and many alloys of copper with precious metals were used for decorative rather than functional purposes, although brass also came to be used in various musical instruments such as horns and bells. Imperial smiths knew of iron, both from ancient experience of meteoric iron, and as a waste product from their extraction of zinc ores [4]. However, their smelting techniques did not produce sufficient heat to melt iron ore, and so they did not make any significant use of the metal.

The spread of literacy allowed the beginnings of the development of a medical profession in the Empire. Doctors in the Imperial era began to make systematic studies of symptoms of sickness and injuries. Clay tablets found by later archaeologists included some handbooks of illnesses, of their diagnosis, prognosis and recommended treatments. Many of these recommended treatments did not actually work very well, since internal illnesses such as fevers, epilepsy and parasites were believed to be spiritual phenomena which required treatments by priests. Still, the early Imperial doctors had some capacity to assist in the treatment of physical injuries, using some basic surgical techniques, bandages, and a variety of lotions and herbal treatments derived from several plants to assist with treatment. They also had a basic knowledge of dentistry, using drills to deal with cavities, using forceps and other specialised tools to extract teeth, and using brass wires to stabilise broken jaws.

Imperial scholars had some knowledge of mathematics and astronomy, although their methods were often basic. They used some rudimentary trigonometry and related methods to assist with calculating engineering requirements, but they had little interest in algebra or other more advanced mathematical techniques. They kept astronomical records on matters which interested them, but they ignored some other aspects. They were aware of the movement of the planets, although they believed that both Venus and Mercury were each two separate bodies, not having made the connection between their appearances in the morning and evening. They kept enough of a watch over the constellations to recognise novas and supernovas. They kept particularly detailed records of comets, which they believed to be a visible representation of the reincarnation of a 'great soul' who would make their mark in the material world in the near future. Being born during the appearance of a comet was a highly auspicious omen, to the point where heirs to the imperial throne would sometimes be chosen based on that fact alone. They kept some occasional records of eclipses, although not systematically, and did not make any practical application of those records. Imperial scholars had no real conception of the shape of the earth; they still assumed that it was flat.

--

Militarily, Watjubaga reached its largest borders in 822 AD. One of their most celebrated generals, Weemiraga, had earlier subjugated the peoples around Port Philip Bay and West Gippsland, and incorporated them into the Empire. In 821-822, he made his great "March to the Sea," leading an army across the Liverpool Range into the Hunter Valley, and then to the Tasman Sea. He imposed tributary status on the city-states in this region. This accomplishment would be recorded in sculptures, murals, and legends, and it saw Weemiraga adopted into the royal family and become First Speaker from 838-853.

At this moment, it appeared that Watjubaga was in a period of ascendancy, but in fact these accomplishments were virtually the last military expansion which the Empire would achieve. Logistical difficulties meant that the Empire would find it difficult to expand further, and the imperial regime soon faced internal problems. After the death of Weemiraga, the succession was contested between three princes, leading to the worst civil war which the Empire had yet seen. The civil war ended in 858, but other underlying trends were further weakening imperial rule.

Imperial rule had relied on two pillars of the state: a solid core of veteran heavy infantry equipped with bronze weapons and armour from the continent's main supply of the metal, who could defeat any major uprising, and a system of garrison-colonies in the far-flung regions of the Empire to maintain a local presence there and ensure the main army would be rarely needed. As the ninth century progressed, both of these pillars were being weakened. The colonisation of Tasmania in the early ninth century provided a rich new source of tin and bronze which was outside the imperial monopoly, disrupting the trade networks and government revenue, and allowing peoples in the southern regions of Australia to gain access to better arms and armour. Subject peoples were also becoming increasingly familiar with imperial military tactics, and through the legacy of several revolts developed ways to imitate or counter these military tactics. Combined with the increased bronze supply, this meant that rebellious peoples could now field soldiers to match the imperial heavy infantry, and the Watjubaga military advantage waned.

The other main pillar of the state was also being undermined by a slower but more significant process of cultural assimilation. The Biral governors and upper classes formed a small minority in most of the outlying regions, and imperial governors came to look more to local interests than the dictates of a distant First Speaker in Garrkimang. Governors assumed more and more de facto independence, and successive First Speakers found it increasingly necessary to settle for payments of tribute and vague acknowledgement of imperial suzerainty, rather than maintaining any effective control.

The weakening of the imperial military advantage was manifested by two successive military disasters. In the 860s, imperial forces were sent to subjugate the Gippsland Lakes region in south-eastern Victoria. This was inhabited by the Kurnawal, a fiercely independent-minded people whose relatives had been one of the two main groups to cross Bass Strait and settle in Tasmania. Thanks to that colonisation, the mainland Kurnawal had access to good bronze weapons, and they largely fought off the imperial forces. The imperial commander conducted several raids and collected enough plunder to bring back to the First Speaker as a sign of victory, but the manifest truth was that the conquest had failed.

Worse was to follow in 886, when a new campaign was intended to launch a new March to the Sea and conquer the Bungudjimay around Coffs Harbour. This time the imperial armies were defeated utterly, unable even to claim plunder. This marked the resurgence of the Bungudjimay as an independent people, and within the next few decades they would begin raids into imperial territory around the New England tablelands.

The defeat in Coffs Harbour marked a devastating blow to imperial prestige. Another disputed succession followed in the 890s. While this did not turn into a major civil war as had happened four decades earlier, it encouraged already-rebellious subject peoples. The Hunter Valley had always been a reluctant tributary, and actual payments of tribute had been largely non-existent since the 870s. In 899, the city-states of the Hunter ceased acknowledging even the pretence of imperial overlordship, and the weakened Empire was in no condition to restore its authority.

While the ruling classes in Garrkimang found it easy to disregard the loss of the Hunter tributaries, thinking of it as only a minor matter, a much more serious rebellion followed. The Junditmara peoples had long resented foreign rule, requiring substantial imperial garrisons. A revolt over labour drafts in 905 provided a trigger for unrest, and in the next year it turned into a general Junditmara revolt. The imperial troops were massacred or driven out of Junditmara-inhabited territory, and in 907 the army sent to reconquer them was outnumbered and defeated. The Junditmara peoples established their own loose confederation to replace imperial rule. They would take what they had learned of imperial technology, literacy, astronomy and other knowledge, and apply it to their own ends. The loss of the Junditmara lands also made imperial rule over the rest of southern Victoria untenable, and they lost everything south of the Great Dividing Range within a few years of the Junditmara establishing independence.

With crumbling imperial authority in the south, the First Speakers turned to one last territorial expansion. The Eyre Peninsula, beyond the Spencer Gulf, had long been disregarded by the Empire. The peninsula was a small region of fertile land separated by a desert barrier from the nearest imperial city at Port Augusta. The land was useful for agriculture, and had some very occasional trading links with the Yuduwungu across the western deserts, but had otherwise not much to recommend it, and the separation of deserts and water made a military campaign difficult. Keen to restore some military prestige, the imperial government cared little for such details, and despatched forces who marched overland from Port Augusta. The Peninsula peoples withdrew behind city walls, and although these were besieged and captured one by one, the long and bloody warfare did not justify the conquest. While the Eyre Peninsula was proclaimed as conquered in 926, the loss of imperial manpower would hurt far more than the minor gain in resources.

After the conquest of the Eyre Peninsula, the remaining imperial structures started to rot from the periphery inward. In the north, the local governors assumed effective independence, although the fiction of imperial control continued for two more decades. The decisive break came in 945. The governors of the five provinces which made up the region of New England had long been more sympathetic to their subjects than the distant proclamations of the First Speakers. The governors announced their secession from the Empire in a joint declaration in 945, bringing the local Biral garrison-colonies with them, and raising additional local forces for defence. Imperial forces were sent to reassert control of the source of tin (and many gems), and were defeated in a series of battles in 946-948. This event, more than anything else, marked the collapse of the Empire. Apart from some brief attempts to reconquer a rebellious Eyre Peninsula in the 970s, this marked the last time that the Empire would try to project military power outside of the heartland of the Five Rivers.

Imperial rule over the core of the Murray basin – the Five Rivers – persisted for much longer than the more distant territories, but with the same condition of gradual decline of imperial power. The Biral remained a resented ruling class along the Murray proper, and revolts became increasingly common. The First Speakers resorted to increasingly desperate measures to quell some revolts, including the wholesale razing of Weenaratta in 1043, but in the end, none of these measures were successful. The lands around the Murray Mouth were lost in the 1020s, Tjibarr rebelled in 1057 and started to encroach further into imperial territory, and Gutjanal [Albury-Wodonga] asserted its independence in 1071, taking most of the dominions of the old kingdom of Gundabingee with it. By 1080, the Empire consisted of little more than Garrkimang and its immediate hinterland; its borders had shrunk even further than the borders of the Classical kingdom. Internal revolt removed the last of the First Speakers in 1124, leaving Garrkimang a decaying city filled with monuments to past imperial glories.

--

[1] The Kangaroos came from Gray, the Corellas from White, the Ravens from Black, the Kookaburras from Blue, the Echidnas from Azure, and the Possums from Red. The old colours of Gold and Green were lost during the migrations.

[2] In modern Australia, this region has been transformed into the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area. This uses a system of weirs, canals and holding ponds to irrigate the area, and which is in turn fed by larger dams further upriver. This has made the area very productive agriculturally. In allohistorical Australia, Garrkimang engineers have developed their own complex system of dams and weirs to trap floodwaters and feed them into wetlands which are used, as elsewhere, for fishing and hunting.

[3] The Five Rivers are the Murray, the Murrumbidgee, the Lachlan, the Macquarie, and the Darling, all of which are part of the Murray-Darling basin. The earlier Three Rivers did not include the Murray and Darling Rivers, but the nation was renamed when it extended control over those two major rivers.

[4] The process which the Imperial smiths have used to develop brass is distinct from that used elsewhere in the world. Early brasses elsewhere were produced from calamine, which is an ore which contains zinc carbonate and zinc silicates, and which were melted with copper to produce brass. In *Australia, the Imperial smiths have explored the massive Broken Hill ore deposits, initially for extraction of lead and native silver, both of which are abundant there. Mining in this deposit will also mean that they discover sphalerite, an ore of zinc sulfide which has also has impurities of iron. This can be melted to produce brass in the same way that calamine was elsewhere, but it also means that iron will frequently be encountered as an impurity in the waste products.

--

Thoughts?