Lands of Red and Gold #16: Regents of the Neverborn

The Yadji, their neighbours call them. In 1618, the Yadji Empire is the most populous nation in all of Australasia; two and a half million people live under its rule. Its dominions include a variety of peoples; the empire is named not after its inhabitants, but for the family name of its ruling dynasty. However, the core ethnicity of the Yadji Empire is the oldest sedentary people in Australasia, the Junditmara, and it was among them that the empire began its growth.

--

The Yadji Empire emerged out of the disintegration of its feudal predecessor, the Empire of the Lake. The old Lords of the Lake had exercised only nominal authority for centuries, and the head of the Yadji family was one of the otjima [ruling feudal lords] who controlled one of many realms. While most of the otjima realms were becoming ever more fragmented, the Yadji were one of three otjima families who became significantly more powerful during the twelfth century.

The Empire of the Lake, already in decline, was devastated by the arrival of Australia's worst native epidemic disease, Marnitja. The first epidemic swept through imperial territory in 1208-10, killing approximately one person in five, and the disease returned in a fresh epidemic a generation later (1238-40). The death toll from these epidemics produced major social and religious upheaval, including setting off a long period of internecine warfare amongst the surviving otjima.

The Yadji were the most successful otjima family to take advantage of this period of warfare. Under Ouyamunna Yadji, who died during the later stages of the first epidemic, and then his brother Wanminong, they launched an aggressive program of military expansion. Ouyamunna created a new caste of warriors who had survived the first stage of Marnitja, and who were waiting uncertainly to know whether they would survive the second stage. In battle, these warriors worked themselves into a frenzied rage, and helped Ouyamunna win a series of battles and subdue his immediate neighbours.

Most of the death warriors died from the fevered delirium or in battle. Some survived the intensive period of battles in the first year, and it gradually became apparent that they would not be consumed by the Waiting Death. Many of the survivors abandoned the death warrior cult at this stage. A few remained in the cult, motivated by the immediate prestige of being raised to a military caste where they had previously been excluded, and by the prospect of a glorious death in battle ensuring that they had a good afterlife.

The surviving death warriors created a new social institution, and they recruited new members from men who were dispossessed or displaced by the internecine warfare of the period. The few men who joined the new elite cult of death warriors shaved their hair and stained most of their faces with white dye, carefully applied to give the impression of a skull staring back at anyone they faced. Under Wanminong (1210-1227) and his son Yutapina (1227-1255), the death warriors were used as shock troops, normally held in reserve during the first stages of a battle, and then used to turn the tide or break the enemy line at a crucial moment. They were never very numerous, but their presence was felt on many a battlefield as the Yadji expanded their rule.

The Yadji were the most successful otjima family who expanded during this period, but they were not alone. Two other families, the Euyanee and the Lyawai, had been increasing in prominence before the Marnitja epidemic, and they also gained territory during its bloody aftermath. The Yadji gained control of much of eastern and south-eastern Junditmara territory, the Euyanee consolidated their power in the south-west, and the Lyawai controlled much of the north.

Between them, the three families controlled about a third of Junditmara territory by 1220. After this, while the internecine warfare continued, their expansion was largely halted, due to a shortage of warriors, and the difficulty of controlling so many new subjects. Many of the smaller otjima families continued fighting amongst themselves for longer, although over time many of them banded together to oppose the great three families, or entered into tacit alliances with one side or another.

The second Marnitja epidemic swept through the Junditmara lands in 1230-40, and was almost as deadly as the first, killing about sixteen percent of the non-immune population. The overall death toll was lower than the first epidemic, since many of the older generation were immune, and because the total Junditmara population had still not recovered. Still, the social disruption was immense, and the Lord of the Lake [Emperor] took the unprecedented step of publicly asking for the otjima to show restraint and calm against their fellow Junditmara.

He was ignored, of course.

All three of the great families made fresh bids for expansion during this time, as did some ambitious lesser otjima. Unlike the previous generation of warfare, though, this new round of internecine fighting saw relatively few otjima families conquered. The lesser otjima were much more inclined to side with each other and resist the advances of the Euyanee and the Lyawai. In this endeavour, they found support from the Yadji. For Yutapina Yadji did not seek to conquer his fellow otjima. When he did fight wars against Junditmara, they were defensive wars to protect his neighbours from the Euyanee and the Lyawai, or their supporters.

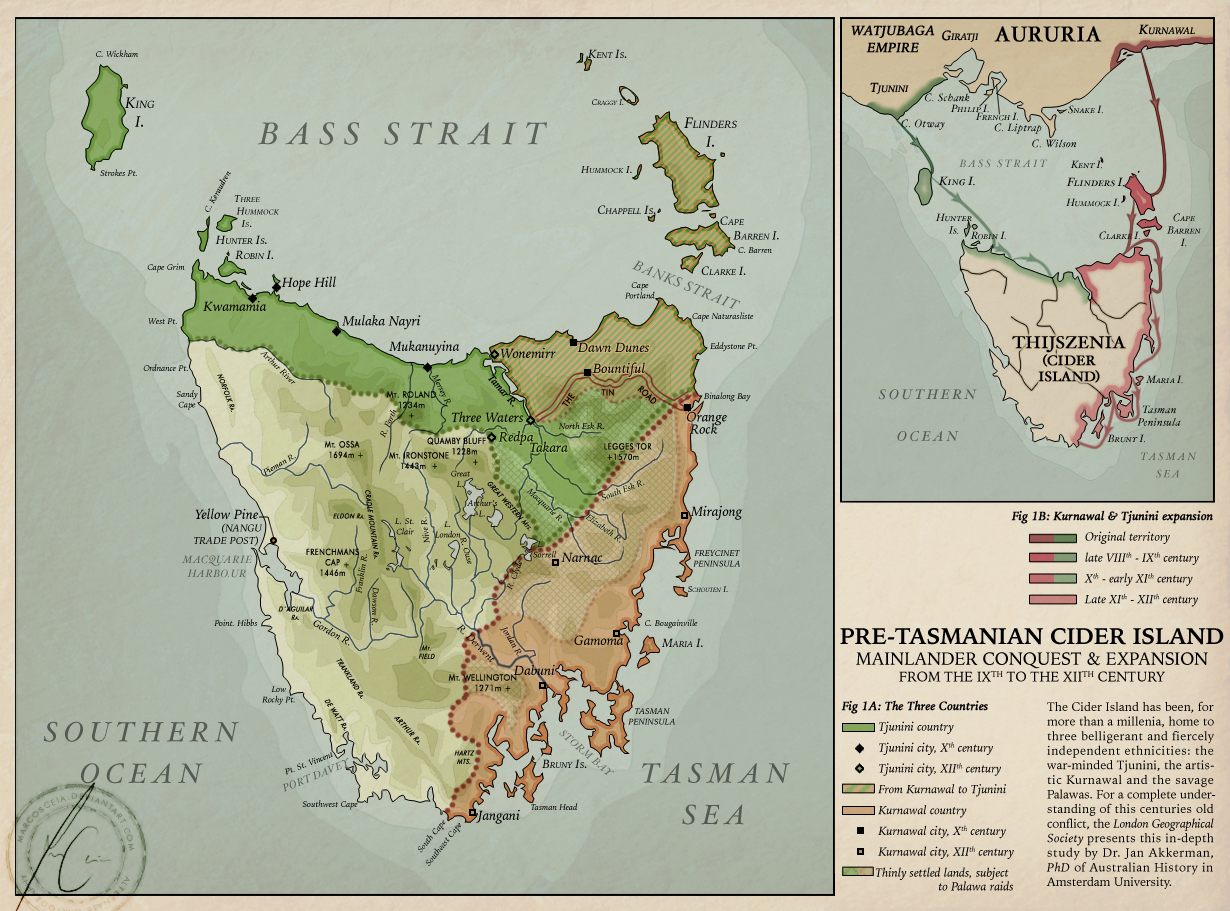

Instead, under Yutapina, the Yadji turned their attention outward, pushing into non-Junditmara lands. They conquered the surviving remnants of the Tjunini along the shore of the Narrow Sea [Bass Strait], and began to expand amongst the Giratji to the east. Here, they had far more success than anyone else had expected; perhaps even Yutapina himself, although history does not record that. The Giratji had internal struggles of their own, due to similar problems with Marnitja. The combination of death warriors and disciplined regular troops proved to be irresistible. Their greatest accomplishment was in 1251, when they captured the gold mines around Nurrot [Ballarat].

By Yutapina's death in 1255, the Yadji had more than tripled the size of their territory, although that included much of the thinly-populated Wurrung Mountains [Otway Ranges]. While they had no meaningful census records, certainly close to half their population were non-Junditmara. By comparison, their two main rival otjima families had gained only limited territory. The Euyanee made an attempt to emulate the Yadji's external conquests amongst the Tiwarang to the south-west of Junditmara territory, but they had only marginal success. The Yadji were now clearly the most successful otjima family.

With their new conquests, the Yadji were no longer a purely Junditmara society. They had to make new accommodations in terms of religion and social organisation, since their old institutions would no longer serve them. They started to rework the fabric of their society into a new form which drew from the old Junditmara social codes, but which had many new features.

Even under Yutapina, they had already started to change the old religious systems. Aided by the many apocalyptic beliefs which were emerging at the time, the Yadji created a new religious system which adapted the old beliefs into a form which suited their rule. Yutapina and his heirs created a new priesthood, with temples at the centre of every community, and who preached of the new faith where the ruling Yadji was the Regent of the Neverborn, and everyone else his subjects.

The Yadji also started to create a strict social hierarchy which was even more rigid than the old Junditmara social codes. Yutapina is reported to have said, "My lands have a place for everyone, and everyone is in their place." In time, the Yadji rulers would decide that the old briyuna warrior caste did not fit into this scheme, since they were loyal to their local otjima and usually not to the ruling Yadji. They would eventually disband the briyuna.

With the new religion and social system they were creating, the Yadji did not fit into the old feudal system of the Empire of the Lake. It made little sense for their rulers to acknowledge the nominal authority of the Lord of the Lake when they claimed divine backing for their own rule. The formal break came in 1255, with the death of Yutapina Yadji. His son Kwarrawa chose to mark his accession in a ceremony where he was ritually married to Lake Kirunmara, rather than paying homage to the distant Emperor. The Yadji would date the creation of their own empire from this moment.

The Empire of the Lake persisted for a few decades longer, but after 1255 it could no longer be considered even a nominal nation. The real power had always been in the hands of the otjima, and now it was being concentrated in the three most prominent families. The lesser otjima started to formally align themselves with the Yadji, Euyanee or the Lyawai, or were conquered by them. The last Lord of the Lake died in 1289 from the third major Marnitja epidemic to hit the Junditmara in the same century, and he was never replaced. By then, virtually all of the Junditmara were either directly ruled by one of the three great families, or their local otjima were effective vassals of one of the three.

In time, they would all be ruled by the Yadji.

--

Ouyamunna Yadji, the ruler who created the death warriors, is said to have believed that they would ensure he had a legacy which would be remembered. In truth, four centuries later, few men remember him, but they have not forgotten the death warriors he created. The death warriors have become an elite few recruited from amongst those who have limited life prospects, and who embrace the opportunity for glorious death in battle. The Yadji still use these frenzied warriors as shock troops in their armies, and they have won many a battle. Under their aegis, the Yadji have become the most populous empire on the continent.

In 1618, the Yadji rule over an empire which they sometimes call the Regency of the Neverborn, and at other times they call Durigal, the Land of the Five Directions. For like many other peoples around the world, the Junditmara perceive five cardinal directions, not four. As well as the more familiar north, east, south and west, they also describe a "centre" direction, the point of origin. Within the Yadji lands, the centre is always Kirunmara [Terang], their capital. All directions within the Yadji lands are given in relation to Kirunmara itself; a man might say that he is travelling "north of the centre" or "south of the centre."

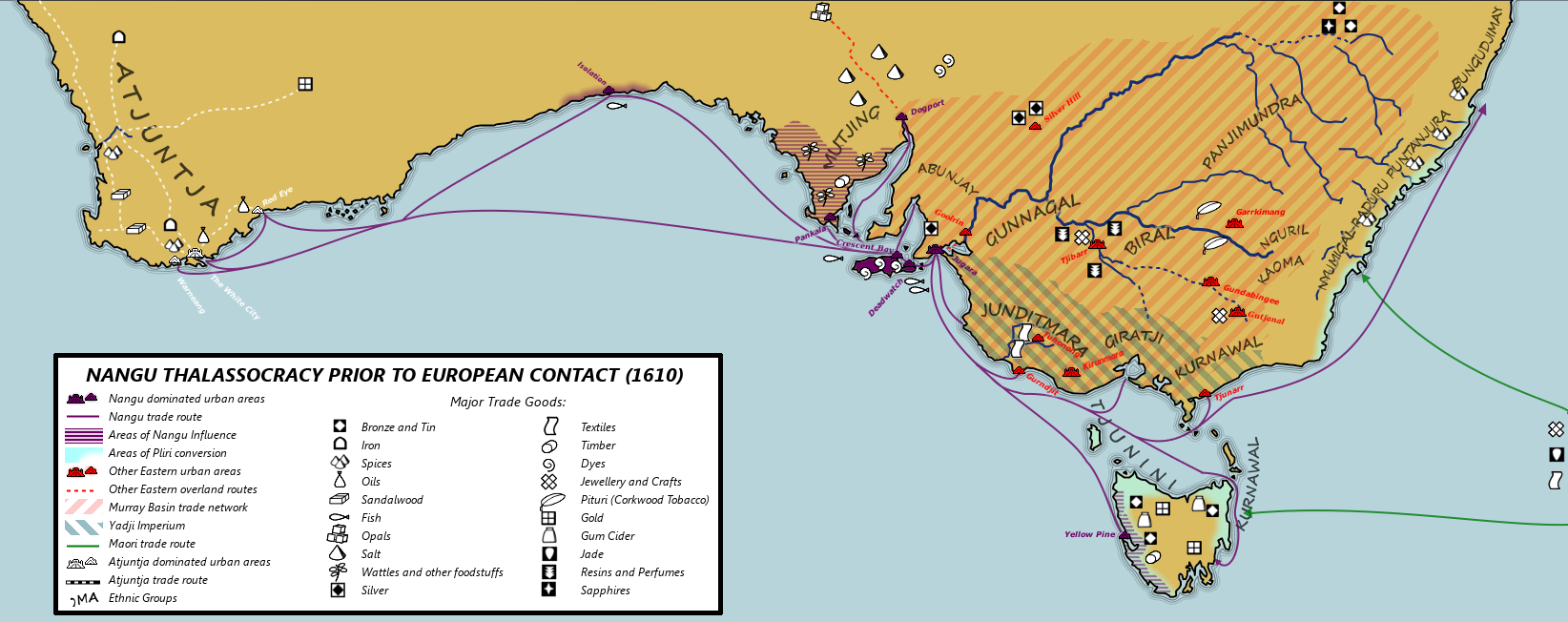

From west to east, the Land of the Five Directions extends approximately from the mouth of the Nyalananga [River Murray] and includes all of the coast as far as the River Gunawan [Snowy River]. Its northern border is usually near the Spine [Great Dividing Range]. Some of these borders are fluid; regular warfare with its northern neighbours, particularly Tjibarr, means that frontiers are contested in the north and northwest. For the rest, Yadji rule is relatively secure, apart from some occasional rebellions over religion, tribute, or language.

The Land of the Five Directions is well-populated, with several large cities and a host of smaller towns and villages. The Yadji divide their lands into four provinces, which roughly correspond to the old ethnic divisions at the time of Yadji conquest. The Red Country stretches from the Nyalananga to just west of Gurndjit [Portland], and its old inhabitants were two Gunnagalic-speaking peoples, the Yadilli and Tiwarang. The borders of the Red Country are the most fluid in the Land, sometimes advancing with military expansion, and sometimes withdrawing due to revolts among conquered peoples or victories by Tjibarr.

The Lake Country is the most populous province; it includes the old Junditmara lands, and some parts of the more contested northerly regions inhabited by the Yotjuwal people. Along the coast, it stretches from Gurndjit to Jerang [Lorne], although its inland boundary is more restricted, and runs generally north-west from Jerang.

The Golden Country consists mostly of the old Giratji lands, although its northern border sometimes includes much of the Yotjuwal lands, except when those areas revolt or are captured by Tjibarr or Gutjanal. The Golden Country includes the gold mines around Nurrot and sometimes those around Djawrit [Bendigo], although the latter mines are sometimes controlled by one of the northern kingdoms. The Golden Country stretches from the border with the Lake Country east as far as Kakararra [Koo Wee Rup].

The White Country is the easternmost province, stretching from Kakararra to the edge of Yadji-claimed territory. Its eastern borders are vaguely defined, because the Yadji claim more territory than they have settled, but their effective line of control is along the lower River Gunawan. The easternmost city of any size is Elligal [Orbost]. Beyond these boundaries lies rugged, difficult to farm territory where the Yadji sometimes raid but do not control. The White Country is mostly inhabited by the Kurnawal, who make reluctant imperial subjects, but who have been largely quiet for the last half-century.

--

While the Yadji rule subjects of a great many languages and religions, they have done their best to centralise their whole empire. Based on their inherited Junditmara social codes, they seek to create a strict sense of local community and common religion, and to impose a broader sense of hierarchy where everyone has their place under the Regent.

Every Yadji city and town worthy of the name has at least one temple at its heart. The temples are the grandest part of each city; built of the strongest stone available in any given area, and deliberately constructed so as to appear larger than life. The temple is the centre of all aspects of daily life. Religious rituals are only one part of that control. Each temple governs all aspects of daily life for the town and the surrounding community, from telling the farmers when and where to work the fields, overseeing hunting and fishing, controlling the building and maintenance of waterworks, giving approval to new buildings, approving or rejecting marriages, overseeing the activities of the weavers and craftsmen, and collecting the proceeds of the harvest. Every temple has attached storehouses where the bulk of the harvest can be retained, including storage for bad years. It is considered very poor practice for any temple to have less than four years stored food available in case drought, bushfires, or pests ruin the harvest.

In their religious practices, the Yadji have created a new religion blended out of some of the older Junditmara beliefs and the apocalyptic teachings popularised after the Marnitja epidemics of the thirteenth century A.D. They teach that the first being was the Earth Mother, and the warmth of her body was the only heat in an otherwise cold and empty cosmos. In time, she gave birth to a son, who was known as the Firstborn. The Firstborn served and loved the Earth Mother, until he found out that she was with child. Jealous that he would have to share his mother's affection, the Firstborn stabbed her through the heart.

As she lay dying, the Earth Mother plucked out her eyes so that she would not have to look upon the son who had betrayed her. One eye she hurled into the sky, where it would circle the world and act as a mirror to reflect the warmth of the earth. Her other eye shattered with tears; the largest shard became the moon, the smaller shards became the stars.

With her dying breath, the Earth Mother cursed the Firstborn to be trapped in eternal darkness and cold. Her blood spilled over her body, creating the mortal world and all of its inhabitants. The warmth of her blood meant that things would always grow, but the Firstborn could not endure the heat for long. He was driven from the surface of the world, out into the darkness of the night. (Hence his alternative title, the Lord of the Night). Here he waits still, waiting and watching. Whenever someone dies, he or one of his servants will descend to the surface of the earth to try to claim the spirit of the recently deceased. The deceased will have to defeat the Firstborn or his servants, or be carried up into the darkness of the night to become another servant. Thus, the Yadji say that one someone has died, he has "gone to fight his Last Battle."

However, while the Firstborn succeeded in killing his mother, he did not kill the child she was carrying. That as yet unborn being still lives, trapped within the flesh of the earth. He is the Neverborn, the true loyal son of the Earth Mother, who waits yet within the warmth of the earth. He is the one who will be born someday to fight his elder brother, and that day will be the changing of the world. All who have died and who won their own last battles wait with him, and will be called to fight at this, the Cleansing, when the universe will be remade.

This, the Yadji teach, is the purpose of the world: to live one's own life in preparation for the world that is to come. They recognise only three deities, the dead Earth Mother, and her two sons, the Firstborn who is scorned, and the Neverborn who is loyal. They also recognise a number of other beings who play a role in the day-to-day world, who are servants of one of the Sons, but they do not view them as gods. Only the Neverborn should be worshipped, since he is pure and steadfast, and the Earth Mother should be honoured and remembered.

To the Yadji, religion is meant to be a unifying force, and indeed many of their subjects have converted to this belief. Not all have done so, though, and religious unrest continues to trouble their empire at times, particularly amongst the Kurnawal in the east. Those peoples who live near the north-western borders are also often more reluctant to follow the Yadji faith completely; they still cling to some of their older beliefs or the teachings of the Good Man [Plirism].

Some Regents enforce religion more strictly, and others care little about the substance of others' beliefs provided that they obey. The current Regent, Boringa Yadji, worries very little about what his people believe. He has concerns of his own; partly staying awake when his generals argue about how best to solve the perennial border wars with the northern kingdoms, and partly how to convince his pet rock to talk. His senior priests have never bothered to dissuade him from his efforts to attain this difficult goal; after all, while the Regent is incommunicado, they can speak for him to the outside world, and this suits them well enough. If he progresses to the stage where he starts to drool too obviously at public audiences, well, they will deal with that problem when it comes. It is a crime beyond hope of atonement to spill the blood of any member of the Yadji family, let alone the Regent, but they will find a solution.

--

The temples control most aspects of life within the Yadji realm, but nowhere is their organisation more significant than their oversight of waterworks and aquaculture. This is the Junditmara's most ancient technology; they have developed it to a level unsurpassed anywhere else on the continent and, in some ways, anywhere else on the globe.

Not everywhere in Yadji lands is suitable for waterworks. However, anywhere that geography, rainfall, and water flow permits, the Yadji will have sculpted the land itself to suit their waterworks, creating the swamps, weirs, ponds and lakes which are their joy.

The ancient Junditmara developed their system of aquaculture into the basis of the first sedentary culture on the continent. It relied on the short-finned eel (Anguilla australis), a species which migrates between fresh and salt water depending on age. Mature short-finned eels breed far out to sea, and the young elvers return to freshwater rivers where they will swim far upland in search of a home territory. The elvers can even leave water for short periods, traversing damp ground in pursuit of fresh territory. Eventually, the elvers find a home range – a stretch of river, a lake, a pond, or a swamp – and establish themselves there. They feed on almost anything they can catch – other fish, frogs, invertebrates – and slowly grow to maturity. The eels are remarkably tolerant of changing environments, tolerating high and low temperatures, murky waters, low oxygen, and going into a torpor state if conditions are poor. The mature eels can reach a substantial size (over 6kg for female eels), and will eventually migrate back downriver to the sea to repeat the process.

Or the eels try to, anyway.

The early Junditmara system of aquaculture was designed to maximise the available habitat for short-finned eels to live and reach maturity, and then trap them when they had reached a decent size. They did this by creating ponds, swamps and lakes for the eels to live while they grew. This involved not just the occasional pond or lake, but long series of ponds with connected waterways, each with enough water to support one or more eels. The Junditmara reshaped the land to suit their needs, using weirs and dams to trap sufficient volumes of water, and creating a myriad array of canals and trenches to connect the ponds and lakes to each other and eventually to the rivers and the sea. Their lands were crisscrossed by an immense network of these canals, all carefully maintained to allow eels to migrate up the rivers.

Sometimes the Junditmara even trapped young elvers, transported them upriver, and released them into suitable habitats for them to grow to a mature size. Their entire system was designed to allow the eels to grow to their maximum size, then trap them before they could migrate back downriver. The Junditmara made woven eel traps and positioned them at well-chosen points along the weirs and dam walls, so that they would trap larger eels when they tried to swim back downriver, but would still allow smaller eels to pass through.

The early Junditmara built their entire culture around farming eels, harvesting edible water plants, and catching waterbirds who fed off the abundance of their waterworks. When they received agriculture from Gunnagalic migrants, the Junditmara were no longer completely reliant on eel meat to feed their population. Still, they never lost their knowledge of aquaculture, and they built larger and more complex waterworks wherever geography and their technology permitted them to do so.

The newer Junditmara waterworks are far more diverse in the produce they harvest than the original eel farms, although 'waterfood' is still a very high-status commodity. Many of the expanded waterworks are too far upriver to obtain a decent supply of eels; sometimes because of the distance itself, sometimes because most of the elvers become established in suitable habitats created by communities further downriver.

The Junditmara have solved this by farming a much greater variety of fish and other watery denizens. They create a series of watery habitats of many depths to suit particular species, and allow fish to migrate between these ponds depending on their habitats. The shallowest waterworks are kept as swamps and marshes with limited depth, but where edible reeds and other plants grow in abundance. Deeper ponds and lakes host a wide variety of fish species; Australian bass, silver perch, river blackfish, and eel-tailed catfish are among the most common.

Some smaller ponds are maintained simply to breed freshwater prawns and other invertebrates to be used as bait by Junditmara fishermen. For some fish species, especially river blackfish, the Junditmara breed them in special ponds and then transport the young fry to stock larger lakes and wetlands. They also keep separate ponds where they breed freshwater crayfish as a luxury food; these invertebrates are slow-growing but are considered extremely tasty. A few Junditmara farmers have even developed farming methods for freshwater mussels (Alathyria and Cucumerunio species), which are treasured not just as sources of food, but because they occasionally produce freshwater pearls.

The Junditmara have amassed a thorough knowledge of which habitats suit the breeding and living requirements of the many fish species in their country. Some fish prefer locations with underwater cover, so the Junditmara ensure that suitable logs, rocky overhangs, debris, or other places of concealment are available for those species. Some fish will only spawn in flooded backwaters of small streams, and the Junditmara hold some water back in dams to flood in the early spring when those fish breed. Many fish migrate regularly throughout their lifecycle, and unlike the engineers who would dam these rivers in another history, the Junditmara make sure that their weirs and dams still allow enough waterflow for these fish to migrate up and downstream as they need.

As part of their aquaculture, the Junditmara also learned much more about how to work with water, stone and metal. They have never developed anything approximating scientific investigation or philosophical inquiry, unlike the classical Greeks who first started to use mathematics to calculate the shape of the world, of mechanics, and hydraulics. Still, the Junditmara have a long history of experimentation and development of solutions by trial and error. This is not a quick process; there have been many errors and many trials. But slowly, the Junditmara and their Yadji successors have developed a remarkable corpus of knowledge of hydraulics and of engineering as it is applied to the construction of water-related features.

Junditmara engineers have become experts at controlling the movement of water. They know how to build very good dams and weirs. By trial and error, they have developed arch dams whose curving structure allows them to build very strong dams while using less stone. Their engineers do not quite understand the principles of forces and calculations and stresses, but they know that the method works. Likewise, they have learnt how to build gravity dams, carefully balanced to ensure that they do not overturn under water pressure. Their engineers have also learned how to build cofferdams to keep a chosen area dry while they are building more permanent dams. They know how to build levees against floods or to keep chosen areas dry even if surrounded by waterworks. Around larger river systems, they build networks of levees, flood channels, and secondary dams to trap floodwaters for later use.

On a smaller scale, Junditmara engineers have discovered how to control water for other uses. They use reservoirs and aqueducts to supply drinking water to their towns and cities. Like their neighbours in the Nyalananga kingdoms, they understand the usefulness of plumbing, but they apply it much more widely. Most Junditmara houses have plumbing connected to sewer systems, and the human waste is collected for fertiliser and other uses. In the temples and the houses of the upper classes, they have flush toilets with a carefully-shaped fill valve which can fill the water tanks without overflowing [1].

The Junditmara engineers have even developed mechanical means of shifting water, thanks to their discovery of screwpumps [Archimedes screw]. They discovered a primitive version of this device more or less by accident, but they have improved its design over the centuries. All of their screwpumps are hand-powered devices; the most typical use is to move water from low-lying ponds into higher ponds as part of maintaining their waterworks. They also make some use of screwpumps to irrigate elevated gardens, drain local flooding, and maintain watery features of their major cities.

--

The practice of aquaculture is the most obvious example, but everything in Yadji daily life revolves around the temples and their dictates. Trade, farming, craftsmanship, and everything else is in one way or another dictated by the reigning priests, who exercise the will of the Regent. In many ways, this is a continuation of the old Junditmara tradition, where their chiefs or other local headmen oversaw their daily lives. The Yadji rulers have applied the same principles, although priests are usually appointed by the Regent or his senior advisers. There is a deliberate policy of moving them between temples throughout their lives, to limit their opportunities to build up a personal power base in any particular region.

Trade and farming, and many of the other parts of Yadji life, have been eased by the Junditmara invention of what was for them a revolutionary device: the wheel. For many centuries the peoples of this isolated continent had never invented this device; perhaps for want of an inventor, perhaps because with few beasts of burden, it would not benefit them as much. For so long, transportation relied on sleds, travois and other means, rather than the wheel. In the last few centuries, however, the Junditmara adapted their existing potter's wheel into a form which worked upright – and which revolutionised their lives.

The Yadji have applied the wheel to several uses. While they are still hindered by a lack of any large beasts of burden, they have converted their old transport vehicles into carts or other wheeled forms pulled by people or by teams of dogs. These are used in their larger cities to transport people and goods. They are also used along the royal roads. The Yadji road network is not as extensive as some other peoples on the continent, but most of their main cities are connected. There are two royal roads which start at their westernmost outpost on the Bitter Lake [Lake Alexandrina], with one running near the coast and the other in the northern regions, converging at Duniradj [Melbourne], then dividing again as they run east, and finally converging at the easternmost Yadji outpost at Elligal. The Yadji also use small hand carts to help with their farming, and this has been a substantial boost to their agricultural productivity.

Yadji productivity would no doubt have been improved in many other areas if they found out how to apply wheels to them. Textiles, for instance, would be easier to weave if they had developed the spinning wheel. No-one has found out how to do this, and the Yadji rely instead on the ancient technology of the spindle for weaving. Still, elaborately-woven textiles were a Junditmara specialty for centuries, and the Yadji have only expanded their use.

For textiles, the Yadji have only a few basic fibres to work from, but they put them to many uses. Their basic fibre is the ubiquitous crop, native flax, whose fibres they work into a variety of forms of linen and other textiles.

For higher-status textiles, they use animal fibres. Dog hairs, to be exact. The Junditmara have bred white, long-haired dogs whose fur is thick enough to be turned into a kind of wool. These fleece dogs are carefully maintained as separate breeds which do not have contact with other dogs; the largest breeding populations are maintained on the personal estates of the Regent. The dogs are fed mostly on eel and other fish meat gathered from their waterworks, and they are shorn every year to produce fleeces and yarns used for high-quality textiles.

The most precious fibres of all are threads of silver or gold. These metals are under strict royal monopoly, and much of the material collected from the mines is spun into thread and woven into the clothing of the imperial family or very senior priests.

From these few fibres, the Yadji have created a myriad variety of textiles, to serve the many needs of their hierarchical society. The fundamentals of their clothing are quite simple. Men wear a sack-like tunic with a hole for the head and two more for the arms, and which usually reach to their knees. Women wear a sleeveless dress held in at the waist with a patterned sash. Both sexes wear the anjumi, a kind of textile headband which has elaborately-woven patterns which indicate a person's home region and their social rank.

Indeed, while the basic aspects of clothing are similar for peoples of all ranks, the Yadji use many colours and patterns to indicate status. They use many dyes, some produced from local plants, some imported by the Islanders or from the northern kingdoms, and they use these to mark status. The patterns on a person's anjumi are an immediate indication of their rank, role in society, and the region where they live. Amongst those of higher status, there are more elaborate indications of status; thread or small plates of silver and gold, lustrous shells, pearls, feathers from parrots and other birds, and other markers to show the wealth and standing of their wearer. It is said amongst the Yadji that even if every person in their realm was gathered into one place, it would still be possible to tell where each person was from, and their rank.

The varieties of clothing which the Yadji wear are only the most visible sign of the careful organisation of their society. For where it has been said that three Gunnagal cannot agree about anything, the Yadji and their Junditmara ancestors have always been a regimented society. The priests act as local rulers, within the broad expectations of the Regent and his senior priests at Kirunmara. To enforce their will, they can rely on both religious authority and the carefully-maintained records of a literate society. For the Yadji make extensive use of writing, using a script derived from the ancient Gunnagalic script. They have never developed any use for clay tablets as their northern neighbours used; instead, they use parchment made from emu hide, and a form of paper made from the boiled inner bark of wattle-trees. Literacy is largely confined to the priestly class and a few aristocrats, but that is sufficient to allow careful administration of the many lands under the control of the Regent.

The same desire for control means that the old military structure of the briyuna has been completely removed. The briyuna were a hereditary class of warriors who were loyal to their local otjima, but no further. The reigning Yadji have no tolerance for warriors whose allegiance is not to the Regent, and the briyuna who survived the conquest of the other Junditmara lands were retired.

In their place, the Yadji developed a new military order based on the careful recruitment of loyal soldiers. Military discipline is strong, with Yadji units very good at fighting alongside each other. They have also developed good methods for coordinating movements between units, using a combination of banners, drums and bugle-like horns.

The spread of ironworking has also revolutionised their military tactics. The Yadji most commonly use a form of scale armour, which they favour as cheaper to produce than the mail which is preferred by their rivals in the northern kingdoms. Part of their preference for scale armour is also because it is easier to decorate; the old Junditmara love of ornamentation lives on in the Yadji military. High-ranking officers in Yadji armies are given sets of ceremonial armour, not just the practical varieties. Designs of gold are common in ceremonial armour, for one of the useful properties of iron is that gold designs show more prominently than on the old bronze armour.

Still, for all that the Yadji have changed, the original ethos of the briyuna has not been lost. Within the Regency's borders, they no longer exist as a separate warrior caste, but many of the retired briyuna took up priestly or related administrative roles in the expanding Yadji realm. Their old warrior code lives on in songs, epics, and chronicles, becoming increasingly mythologised and romanticised, and the ruling Yadji have tolerated this development. The code of the briyuna is still seen as the standard by which a proper Yadji gentleman should conduct himself, even if this standard is more honoured in the breach than the observance.

As for the briyuna themselves, they did not completely vanish when the Yadji dissolved their order. Some of the briyuna refused to accept retirement, and fled beyond the borders of the Regency. A few went to the northern kingdoms, but the largest group fled to the Kaoma, another non-Gunnagalic people who live in the highlands beyond the Regency's eastern border. There, the briyuna have become a warrior caste amongst the Kaoma and their neighbouring Nguril, and they still preserve much of their old code and lifestyle. They have not forgotten their origins, and they still mistrust the Yadji who evicted them from their old homelands.

--

One of the perennial questions which has vexed linguists and sociologists is whether language shapes society, or society shapes language. Or, indeed, whether both are true at once.

When they come to study the Yadji, they will find a rich source for further arguments. For the Junditmara who form the core of the Regency's dominions have developed their own extremely complex social rules regarding their interactions with each other. The rules dictate who can speak to whom, the required courtesies and protocols needed when people of different status meet, what subjects can be discussed with which people, and a myriad of other intricacies. The Junditmara are status-conscious in a way which few other peoples on the globe would recognise.

The intricacies of Junditmara social codes are reflected in their language. All Junditmara pronouns have six different forms, which can be roughly translated as dominant, submissive, masculine, feminine, familiar, and neutral. Their language also uses a variety of affixes which are added to individual names and titles, and which carry a similar function to the pronouns.

Each of these forms indicates the relationship between the speakers. Dominant and submissive are broadly used to indicate the relative social status of each of the speakers. Using the dominant form with a person of higher rank is a major social faux pas at best, and is usually treated as a grave insult. These two forms can also serve other functions, such as when two people of similar rank are arguing, one might use the submissive form of "you" in a form such as "I agree with you" to concede the argument.

The masculine and feminine forms have the fundamental purpose of indicating the gender of the person being referred to, but the customs regarding their use also reflect social rules amongst the Junditmara. When speaking to a person of higher social status, a person will normally use the submissive form rather than a masculine or feminine form. When speaking to a person of roughly equal social status, the masculine or feminine form is typically the form used. When speaking to a person of lower status, a high-status speaker may choose to use the dominant forms, which indicates a greater degree of formality, or the masculine or feminine form, which indicates a less formal meeting. As with all aspects of Junditmara society, these forms can be used in other ways, such as if a group of soldiers wished to condemn another soldier for supposed unmanly or cowardly behaviour, they would typically refer to him using a feminine form.

The familiar and neutral forms are more restricted in their usage. The familiar form is normally used only for relatives or close friends, and indicates that the relationship between the two people is so well-established that questions of status will never arise [2]. It sometimes has other uses, such as being used with someone who is clearly not on familiar terms, which indicates either irony or extreme disrespect. The neutral form is used mostly in ambiguous situations where people have only just met and are not sure of each other's status, or a situation where someone of lower status temporarily needs to be treated as being of equal status. Some subsets of society also use the neutral form if they want to indicate that they are completely equal. For instance, amongst soldiers, men of the same rank are expected to refer to each other using the neutral form, rather than the masculine form.

The intricacies of Junditmara language extend to many of their other words. Most of their common verbs have two different flavours, which can be described as directive or suggestive. Directive means that what is said is a command, while the other indicates a request or a preference. "Come here" if said in a directive flavour would have a rather different impression upon the listener than if it were said in a suggestive flavour.

While the intricacies of the Junditmara language are not directly matched in that of the other peoples who make up the Yadji Empire, some of their phrases and meanings are slowly diffusing amongst the other peoples. For the Junditmara language is the effective language of government amongst most of the Regency; even if priests speak a local language as well, they will be literate mostly in the Junditmara tongue. This is one of the many methods which the reigning Yadji use to centralise control over the dominions. Religion, however, remains the most important aspect of their government. Up until the year 1618, this has been very effective in maintaining their rule over a disparate group of peoples. As that year draws to a close, however, a new era is preparing, one in which all of the social institutions of the Yadji will be sorely tested...

--

[1] This is a similar type of mechanism to the ballcock which would historically be developed in the nineteenth century.

[2] The familiar form is used in approximately the same manner as "first name terms," back in a time when being on first name terms actually meant something more meaningful than having said hello. Or the distinction between tu and vous in French (or similar forms in many other languages).

--

Thoughts?

.png)