The liberation of Poland and the Vasa triumph

(1617)

(1617)

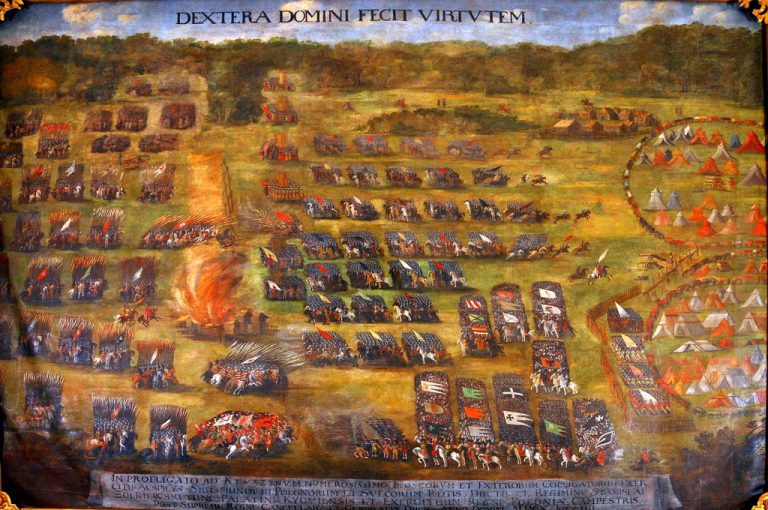

Victory, much desired in Kraków, was finally achieved. Rising from the ashes of the German Deluge was a man hardened by years of war and insuferable humilation, as great as it could be for a person of royal rank and dignity. Władysław, the heir of the Grand Ducal household of Gedymin; Władysław Jogaila, the harbinger of Lithuanian Catholicism; John III of Sweden and Sigismund III of Poland-Lithuania and Russia and countless others, be it Habsburg or Sforza princesses, now had to content himsellf with a status no better than the duchies of the Danube river, subordinate to the Sultan in Constantinople. His mounting frustration and ease of anger was overcome by his grand triumphs: the subduing of the Habsburg pretender Maximilian and enforcement of his senioral status in Ducal Prussia. It not only showed the supreme power over Poland-Lithuania owed to him: it were the deeds of chivalry that struck the greatest accord. Much from a young age had the Vasa boy been fascinated by military tactics, strategy, and technology, the so called ars militari. These were of great use during the crisis started by the deposition of the great conqueror of Muscovy, Sigismund III, and Władysław used these to his advantage, keenly observing the performance of the troops and his commanders, sometimes suggesting his own course of action and reflections on the art of war. The king, however, was deemed too young and too important to be left to his own devices on the field of battle, and it had been decided by the great elders of the Commonwealth, the senatores, that the monarch better keep watch of the battle from a hill rather than the frontlines: a much fortunate decision, seeing Władysław as the last Vasa heir, his cousin, Gustav Adolph, not being a descendant of Cathrine of Jagiellon and John III of Sweden, could hardly be seen as a true heir to the Royal and Grand Ducal domains. With no other kin to sooth over the anxieties of the Polish elites Władysław had to listen obediently, especially that his rule depended on their approval and good will.

Władysław as a young man, in so called Polish dress

The occupation of Pommerania, Greater Poland and Masovia, with it's capital Warsaw, and the subsquent stalemate that followed could hardly be rectified by military means, as much as the Vasa king would like it to happen. Insubordination, lack of command structure, noble pride, no funds and standing army all contributed to the great problem that all monarchs from the time of Alexander the Jagiellonian faced: lack of a true army. Archaic in it's essence, the Polish-Lithuanian domains depended in it's time of need not on standing armies, seen in the Habsburg domains or France, or well paid condottieri of the princes of Italy, but on the pure birth and bravery of it's noble levy. These showed time and time again, starting in the Thirteen Years war (1453-1466), that no true Renaissance monarch could rely on medieval tactics and organisation. Lacking in sophistication, these levies contributed to the severe crisis of the military structure. Unable to use a true military, seen in other kingdoms, the Jagiellonian monarchs resorted to the refuge of nobility: deception, prestige and diplomacy, overhelmingly the last one. Sigismund the Old put these to great use resolving the Teutonic crisis that made his nephew, Albrecht von Hohenzollern, his vassal, and used the power of scheming and diplomacy to break the Habsburg-Muscovite alliance, ending their short flirt once and for all. Later king's followed suit, maybe less so king Stephen, the Batorean magnate from Transylavania, but the point and precedence stood: the domains, which the Vasa, after the fall of Sweden, called their new home, were built on a weak defensive position, both organisationally and geographically. It swiftly became a practical, though dangerous workaround: diplomacy and contentious interests of the Commonwealth's rivals had to be enough for it's monarchs to defend. It didn't mean that Poland-Lithuania had no army, it sure had and it was a force to be reckoned with, but it's fundamenals were weak for a stable political and military strategy.

In the grand scheme of things, this Jagiellonian born policy had to be used again with great precision as to reedem the land from more war and total apocalypse, only seen in the old books of the Scriptures. Further devastation served no one, and the shrewd senators saw it with the greatest hindsight. The war had to be finished as soon as possible to spare any more destrcution that could destroy the kingdom's potential even more and for more decades, annihilating the Vistula valley for Poland's future success. Some even doubted and deemed it was too late, though their innate patriotism and sense of being guardians of the country made them keep silent. First on the list was none other than Maximilian von Habsburg, once and again pretender to the Polish crown. Seeing no end in sight for the Polish stalemate and devoid of support from his Imperial kin he had seen recourse in the Jagiellonian strategy mentioned before. His offer, arrogant as it was, was seen as sensible by the chief oarsmen of state: compensation (with a title, without a land grant, not yet invested or specified), amnesty for his followers and free operation of the Teutonic Order in the Vasa kingdom. With the matter settled, Maximilian retreated to the safe space of the Habsburg domains, and that left one great enemy for the Polish-Lithuanian forces.

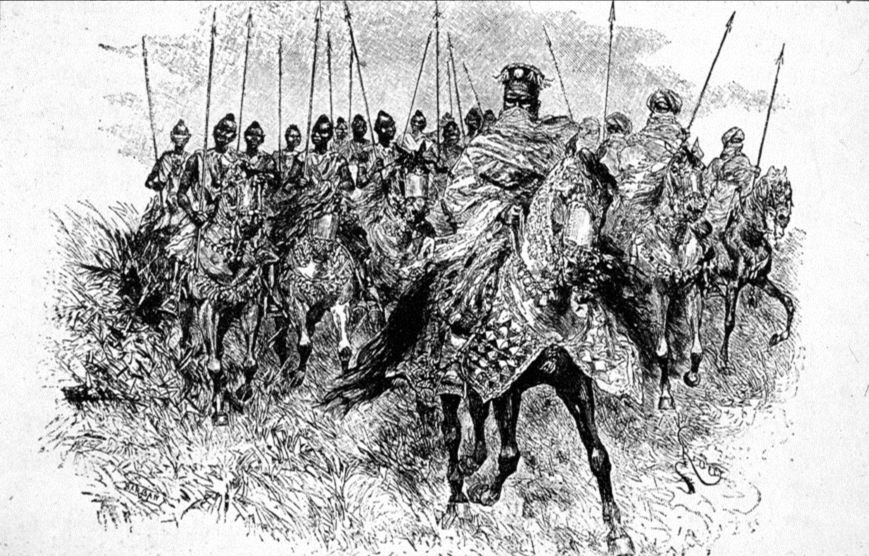

Charge of the Polish Hussars

Hohenzollern-Vasa relations deteriorated progressively during the reign of Sigismund III, their drastic culmination seen in the Hohenzollern invasion of Royal Prussia. A hatefull relationship developed, where the Polish camp saw the Brandenburgers as great upstarts and traitors, breaking their vassal's oath and attacking their liege lord, especially in a time of great need. This in turn was resembled by the Electors accusations of senioral ignorance, infringment on the rights and freedoms of a vassal, breaking of oaths and agreed on treaties. With tensions high and open war ongoing the conflict became very personal and vicious, with hate pouring from both sides. During negotiations, messengers rode time and time again to their camps, bringing their lords to cries of anger. Agreement was almost undone when the Brandenburger messenger told to the king and Polish magnate's assembled at the royal residence at Wawel Castle that the Elector demands Royal Prussia be added to the German domains. The king, easy to anger, proclaimed aloud that war will continue until the last spill of Hohenzollern blood touches the earth. That led to a great reaction from the Polish nobes, who shouted long and unrepentantly Vivat Wladislaw rex !, which showed to the envoy the great popularity the Swedish-descended king had among the nobility, especially ordinary middle and lower szlachta. Finally, calmer heads prevailed, especially from the bishop's side. After the Senate met on a emergency meeting, negotiations continued with a counter-offer from the Polish, with a suggestion of continued war, led the envoy to be more open to the king's offers. Some more rounds of back and forth followed, but these were minor inconviniences: peace had been finally made.

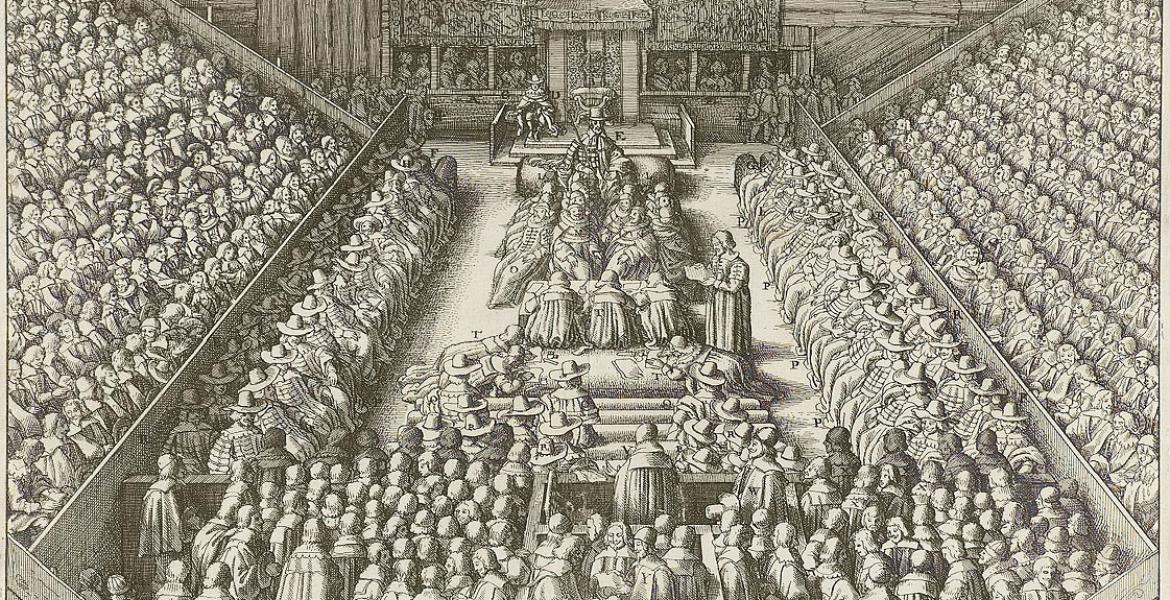

King, Senate and the Chamber of Deputies together formed the Sejm

King in center, senators near him, the rest of the hall filled by the Deputies

The Jagiellonian strategy once more showed it's true force, prevailing over brute might. One city was left defiant however and a kingdom still had an uncrowned head.

The double coronation and election Sejm had not been an magnificent affair, with the treasury empty after a series of devastating war's that left the neighbors of the Polish kingdom without suspicion about it's abilities, prestige or might. Wawrzyniec (latin Laurentius) Gembicki, in his capacity as Archbishop of Gniezno and Primate of Poland and Lithuania held the sermon as the formal interrex during the election phase of the Sejm, extolling the virtues of the king, his patriotism and devotion to God and for his subjects. He once more admonished the Polish-Lithuanian szlachta, both high and low, in the style of Piotr Skarga, about the dangers of discontent, disobedience and civil strife, words that reasonated mightily with the assembled after the recent invasions. Others, consumed by the spirit of Golden Liberty, remained weary of such regalist orations. Nonetheless, the election proceeded, though after recent events only a formality, and the szlachta unanimously elected Władysław, son of Zygmunt III, as their king and grand duke. The coronation, as mentioned before, was the next logical step, normally with the coronation Sejm a different affair happening after the electionary one. Difficulties of the last years led to the culmination of both of these, but it was meant to be only temporary, a breach in the proper traditions of the Commonwealth. The sermon was in essence the same, though more virtues of the new king were extolled, and proper warnings against a life of sin heard.

The double coronation and election Sejm had not been an magnificent affair, with the treasury empty after a series of devastating war's that left the neighbors of the Polish kingdom without suspicion about it's abilities, prestige or might. Wawrzyniec (latin Laurentius) Gembicki, in his capacity as Archbishop of Gniezno and Primate of Poland and Lithuania held the sermon as the formal interrex during the election phase of the Sejm, extolling the virtues of the king, his patriotism and devotion to God and for his subjects. He once more admonished the Polish-Lithuanian szlachta, both high and low, in the style of Piotr Skarga, about the dangers of discontent, disobedience and civil strife, words that reasonated mightily with the assembled after the recent invasions. Others, consumed by the spirit of Golden Liberty, remained weary of such regalist orations. Nonetheless, the election proceeded, though after recent events only a formality, and the szlachta unanimously elected Władysław, son of Zygmunt III, as their king and grand duke. The coronation, as mentioned before, was the next logical step, normally with the coronation Sejm a different affair happening after the electionary one. Difficulties of the last years led to the culmination of both of these, but it was meant to be only temporary, a breach in the proper traditions of the Commonwealth. The sermon was in essence the same, though more virtues of the new king were extolled, and proper warnings against a life of sin heard.

Wawrzyniec Gembicki, Primate of Poland and Lithuania

The coronation itself, being as it was modest for such a monarch, still was held in esteem by the attendes. Fanfare and general joy followed, some wept, some cried from excitement: the formalities were over, tradition upheld and now the Polish citizens, the szlachta, soil of the land, finally had one, crowned monarch, in the original Polish regalia stolen and now given back by the pretender Maximilian in the recent peace treaty. The finishing touch of the Sejm was holding court by the newly coronated monarch. Petitions were heard from the interested parties, more importantly than that however the king enacted his first, very own, policy decisions, not just enacted by his advisors like before. One of these was the abandonment of the so called for life Crown Chancellorship of Jan Zamojski. The practice, from the onset flawed, was something far removed from Polish-Lithuanian political life and never seen before. Reverence was paid to God, king and fatherland, not to public persons, even if rich or popular. It was not a suprise then that it quickly became a point of contention, especially reviled by the magnates of the realm, who, like the rest of the nobility, discontended themselves with such overemphasis on one of their own. Władysław acted with these informations, and quickly got rid of the troublesome arrangement, presenting himself as the guardian of Polish political culture, a move well seen by the noble massess.

Stanisław Żółkiewski, Grand Crown Chancellor

The now free position has been filled by none other than Stanisław Żółkiewski. He was perfectly fit for the role: a polyglot, thanks to the grandeur of the Zamość court where he mastered Italian, French and German, though Latin was still his favourite recourse (Ceasar being his favourite writer); very well educated (finished the Jesuit college in Lwów/Lviv), knew how to behave at court and on the field of battle. His mentor, Jan Zamojski, teached him the intricancies of politics, taking him to Paris for the encounter with Henry of Valois, future and short-lived king of Poland. Under the protection of the great magnate he also learnt the art of war. The next great mentor in this regard was no other than king Stephan Batory, who's personal secretary Stanislaw became. That great education and early life journey provided the future hetman with mastery of the feather and the sword, the last one especially. His early success led him later to greater heights, with the Russian campgain of Sigismund III being the, as of today, coronation of his military carrer. After that things have changed for the Commonwealth, with the insuferable defeats against the Turks and Russians greatly damaging the honor of the hetman. The promise of revenge, or at least partaking in the rebuilding of the kingdom, greatly reinvigorated the old statesman. His anti-Turkish rhetoric a boon to Władysław, who could comfortably disspel any rumors of him loving the muslim Turk. Of course the greatest advantage that it brought was the advanced knowledge, acumen and experience that Żółkiweski brought to the machine of state, now devoid of the Sigismundian ministerial system that so obediently answered to the absolutist tendencies of the late king. With the Polish and Lithuanian noblity vehemently opposed to any expansion of royal power, even so much that the abrogation of the Vasa ministries was included in the pacta conventa of Władysław, the monarch had to use the old system of traditional state ministries, which Żółkiewski now became part of. His candidacy could also be welcomed by his old friends, the Zamojski, now disheartened by the dynasty's cold shoulder showed to them by the recent actions of the king and rulling class. Now Żółkiewski could patronise his mentor's son Tomasz and heal some of the wounds opened during and before the war.

Jan Piotr Sapieha, the greatest Lithuanian magnate (for now)

Grand Ducal Chancellor

In the Grand Duchy a status quo policy was prefered. Knowing the power of hetman Sapieha, the royal court, now moved to Warsaw, made it abundantly clear that it rejects any kind of conflict with the Lithuania potentate's family. Inclusion in the Ducal machinery was the strategy. Jan Piotr, the greatest of the Sapieha, was given the Chancellorship of Lithuania for his service and achievements during the crisis. More importantly however, it was meant to pacify the overambition of the magnate house that already became a troubling sight. No one could forsee the consequences of Sapieha might, for now however the house had to be accomodated into the political system. Speaking of Jan Piotr personally, he did distinguish himself as a commander and skillfull leader for his soldiers, fighting the Tatars and Wallachians with his father, the Kiev castellan Paweł Sapieha. Certainly he was well educated, learning at the Vilnus Academy (till 1587), and later at the University of Padua. His greater accomplishment however was king Sigismund's war with Muscovy, for which he greatly agitated for at the recent Sejm's. The military talents of Sapieha saw great display during this war, and later on his experience helped him to succesfully fend of the Muscovites, Turks and Prussians, with the taking of Królewiec (Konigsberg) his major achievement. Nonetheless, Jan didn't possess the sheer intelect of his Crown counterpart, nor such a magnificent eduaction or erudition. Time would tell if he could rival him in politics, as at the military side it was obvious who had the upper hand (Żółkiewski of course). The rest of the Sapieha's were paid off with land or office grants. A deal between Sapieha and Vasa was struck, time would tell how long it would last. For now stability reigned in Lithuania.

One obstacle was in the way of winning the peace, Gdańsk (Danzig), the defiant city. Usually, relations between the city and king had been amicable, even warm, with short interludes of conflict. Major freedoms were granted to the city by the Jagiellon monarchs, who cherished and guarded the Danziger merchants. Their priviliges left them with the power of minting their own coins and conducting their own trade policy. Substantial autonomy was granted to the townsmen, which practically meant self-rule. The wealth from the Vistula trade had been flowing, and the traditional compromise based relationship between the Jagiellons and their subjects meant that they didn't show any will or action to infringe upon these priviliges. The first major conflict happened in the 1520's, was short-lived and of small importance, religion and inner conflicts of the city being a prime mover. A royal crackdown followed, when Sigismund the Old had the instigators cut down for their transgression. Some anti-Lutheran edicts followed, by the same Sigismund, but their lax employment ment that Lutheranism could freely grow, even with some anti-Catholic actions to boost. That episode meant the end of conflict for many years, and could be seen as inner turmoil, not aimed at the monarchs themselves. Peace followed, with the son of Sigismund the Old, Sigismund Augustus granting a tolerance privilige to the city, where freedom of faith should be followed, in contrast to his father's policies. The first true conflict with the Crown was conflated with the election of Stephan Batory. Gdańsk, a grand trade emporium, was meant to benefit from trade priviliges upon the election of a Habsburg candidate, the first being Ernst von Habsburg, and later, during the election of Sigismund III, Maximilian von Habsburg, two-time pretender to the Polish throne. War followed with Stephan Batory and with no sight of victory for either side, compromise was reached, with Danzig holding and even expanding it's freedoms and priviliges. The hated statues of Karnkowski (1570), which subjugated the Danziger city council more thoroughly to the king, and formally monopolised the king's right to own the Gdańsk fleet, were abrogated, with Gdańsk agreeing to fund Stephan's war with the Muscovite tsar Ivan IV in return.

Gdańsk (Danzig)

This new conflict with the city, starting just after it's forces were defeated by the Brandenburgers and proclaimed their loyalty to Władysław before, came as a major shock to the king and his advisors. Time and time again the king's envoys tried to plead them to reconsider, promising all freedoms to be upheld, with time and time again being rebucked. With the lack of concilliatory attitude both sides prepared for the inevitable. After the conclusion of peace with the Hasburg-Hohenzollern coalition, Gdańsk was the last defiant force that stopped the Vasa to fully controll their Commonwealth. The Polish forces, hardened by years of battle, were ready to act upon their kings command. Swiftly moving in the direction of Gdańsk, hetman Jakub Sobieski set up camp before the city, with siege artillery shooting furiously at the rebell's. Possibly, under the right circumstances, the city would fall easily before the Vasa troops, alas nothing is given for free. Lack of a proper fleet once more proved problematic for the Commonwealth's military abilities, with the city given ample support from Protestant powers and magnates abroad through open sea lines. Time flowed and Gdańsk stood defiant, with no end in sight to the conflict.

Danziger footmen, Court of Artus, Gdańsk

This proved intolerable to the Warsaw court, which feared continued war and destruction. With funds depleting, a new strategy had to be taken, that of diplomacy. Once more, the envoys of Władysław agreed to uphold all priviliges and freedoms, uphold the autonomy of the city, with their own fleet and militia. This, combined with furious assaults of Polish forces and economic interests of the Crown and city correlating, lent ample room for negotiations. Finally, the city agreed to these conditions. With peace concluded, the Polish-Lithuanian realm sighed with relief. Now the ardous task of rebuilding was at hand, one that was happily greeted by the grandees, as well as commoners after all the devastation that the Antemurale Christianitatis had to suffer throughout these years.