East Asia Report 1614-1616

- Location

- Multiple.

The Three Brothers of Legend, Guan Yu, Zhang Fei and Liu Bei

War in the Celestial Empire

The Battle for Yanzhili & Beijing

The advance of the Western Pacific Army eastward to strike at Beijing would progress with great success in the opening months of 1614, as Qian Shizhen defeated the local guard units stationed across the Yellow River in Henan and promptly assumed position in Kaifeng. News of the rebellion of the 'Sensing Incense Sect' and the declaration of its new 'emperor' the so-called Xingsheng Emperor would inspire an even more rapid push of Qian Shizhen upwards to the north, receiving the submission of various defected guard units and the alliance of Huo Meng, a local scholar in command of a peasant militia. Meanwhile, the Xingsheng Emperor commanded a massive force of 120,000 peasant militia and some trained fighters from defected guard units and patrol officers.

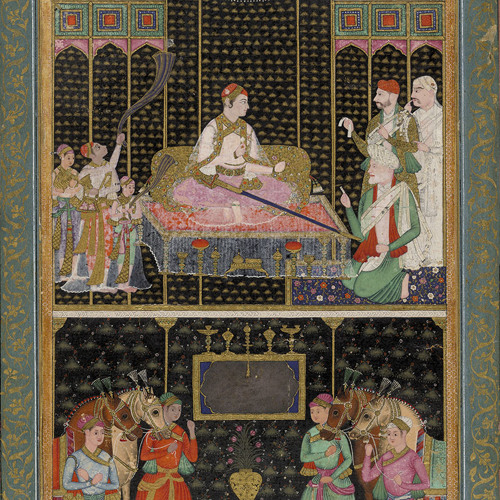

Perhaps expecting the situation, the Chief Eunuch supported a strategy of wu-wei, of allowing his enemies to fight each other and destroy the territory, while he prepared his own defenses around the Forbidden City and recalled forces from the Liaodong Commandery to rescue Beijing. The strategy relied heavily upon Wei Zhongxian's faith in the ability of Zhu Zhilan, Commander of the Imperial Guard and possessor of the title of 'Dragon Commander' to hold the city of Beijing against all incoming attacks and the rapid approach of the Northern Pacific Army, all of which were unsure strategies. However, Wei Zhongxian lacked much choice in the matter after his commissioned forces, all too inadequate and almost the entire capitol province fell to rebellion or defection and thus desperate times called for desperate measures. The Wanli Emperor meanwhile remained more or less focused on different affairs, namely his various concubines, and incessant playing of the board game go, all by design of Wei Zhongxian who monopolized control over the palace. Zhu Zhilan complemented Wei Zhongxian's power over the palace by assuming in 1611 the position of 'Mayor of Beijing' and subsequently being promoted to Commander of the Imperial Guard, where he and Wei Zhongxian controlled the capitol with an iron grip that was unbreakable politically.

Empress Xiaoduanxian, 1616

Within this tight control however, the Crown Prince, King Fu existed as a further ornament and puppet supposedly under the control of Wei Zhongxian. King Fu owed his position as Crown Prince to Wei Zhongxian and Zhu Zhilan and thereby respected them immensely, and he displayed his respect by supporting the reigning government in all the ways he could. However, King Fu was a noted drunkard and disinterested in state affairs and often vacated the palace to go drink and enjoy himself in the city, even amidst the conflict across the capitol province. King Fu notably began residing in taverns, drinking to his heart content with eunuch comrades and with a curious collection of scholars from the local Hanlin Academy.

Hanlin Academy was one of the major academies housing scholars for the Great Ming in the capitol and had in the past held great importance, but with the rise of the Donglin Faction, had fallen into decline. However in 1609 it accepted a scholar and military student named Sun Chenzhong, who had previously served in various roles in Zhejiang, Anhui, and in Jinan as guard captain, prison warden, and commander of 'bandit suppression forces.' Sun Chenzhong was noted for his unique ideas wherein he wrote frequent memorial to the Palace suggesting the reduction of army sizes and improvement of military salaries to create a more efficient military that was organized, discilpine, and able to crush bandits more sufficiently. Sun Chenzhong was likewise joined by his comrade from Hanlin Academy, Qian Qianyi, who was a military official noted for his exquisite poetry, skill in tactics, and erudite qualities. Previously serving as Guard of Anhui, Qian Qianyi was a famous figure but often degraded by his contemporaries for being untested and a soft man of fragile build. The two scholars from Hanlin joined King Fu in carousing about Beijing and quickly the three became supporters of each other, their support would become important in the coming month wen the whole of the Ming Empire would stand still for a week of mayhem.

The key battle in the Yanzhili province was the conflict over the city of Beijing, which quickly was put under siege by the Xingsheng Emperor and his great rebel army of 120,000 fighters. Zhu Zhilan struggled to defend against the onslaught while the Wanli Emperor issued an edict from the palace recalling an army of 70,000 fighters from the Northern Pacific Army. A three pronged force was dispatched by the Northern Pacific General, Xiong Tingbi, who sent forth Interim General, He Xian to lead the main force, alongside a collection of other commanders. The force dispatched also brought 6,000 Jurchen, 11,000 Chahar Mongols, and 53,000 Han soldiers. Ligdan Khan led Mongol forces, hoping to in the campaign not only secure merit and pay, but receive support directly from the Ming Court to launch his third campaign to retake control over the Mongols in alliance with the Great Ming. Jurchen forces were led by a Han Chinese commander known for his relation to the Jurchen named Li Kezhou, an unscrupulous man who was known to be treacherous and greedy. The other commanders of the Ming forces from the north were Mao Wenlong, an ambitious and hot headed commander known for his merits in Korea, a Mongol commander named Man Gui who had served the Ming as a captain and warrior since 1607, and the aged but well learned commander Chen Di, a veteran of war against Japan and pirates. However the clock was short and few knew if the Northern Pacific force would arrive in time to liberate Beijing.

Interim General, He Xian, 1615

In the city of Beijing, in the western sector, a riot erupted led by a certain Gui Han, who declared 'Heaven is a Pearl, and Enlightenment an Incense' and rose a flag in the 'western market' bearing two words, 'Perfected Pearl,' thereby starting a local insurrection of merchants and artisans presumably against taxes and in favor of the Xingsheng Emperor. The rebellion in the Western Market would cause disunity in the Imperial Barracks and several of the municipal captains, indoctrinated into White Lotus thought launched a mutiny of 60 soldiers, breaking into the HQ of Zhu Zhilan and taking his head and escaping with it. Using the commander seal, the mutineers would thence open the Western Gate, allowing the rebels to flow into the city of Beijing; chaos began.

The rebels entered the city and mayhem ensued as the discipline of the peasant rebels disappeared in the face of vast loot and destruction. Even the arrival of the Xingsheng Emperor into the city on a white chariot would not hasten the end to the looting as the western section of the city fell into enormous chaos. In the face of the destruction, Wei Zhongxian acted decisively, ordering the defense of the Forbidden City and commissioning members of the Hanlin Academy lead the remainder of the Imperial Guard to defeat the rebels. King Fu's friends, Sun Chenzhong and Qian Qianyi were mentioned and given commander over the Guards and sent forth. Additionally the Wanli Emperor awakening from his stupor issued an edict to the populace carried by the Surveillance Envoys to call the populace to rise u[ with all available weapons and drive out the rebels, bandits and suppress heterodox doctrines. Meanwhile, the Xingsheng Emperor attempted to control his rowdy army, but the situation was out of his control rapidly. Sun Chenzhong focused his crack warriors on attacking the western market while Qian Qianyi guarded the Forbidden City. The fight would see the Ming forces defeat the rebels, who were quickly taken unaware, and the Xingsheng Emperor confused and assuming a general Ming force had arrived, fled the city out of the Western Gate, while his commander, Han Ying and Xu Gao were slain by Ming Guards as they fled and the seal and banner of Zhu Zhilan were recovered.

As the Xingsheng Emperor fled, the White Lotus rebels and their captains turned about and found much of the army fleeing the city and thus were caught in a vice grip as Qian Qianyi and Sun Chengzhong launched urban attacks across the western and southern sectors of the city. Meanwhile to the north, He Xian finally arrived to rescue the city, just in time as the Xingsheng Emperor had turned around and resumed the siege and if not for the arrival of He Xian, he would have retook the city. He Xian had wisely split his army for the advance and attacked the enemy from many angles to cause confusion and devastation across the White Lotus front. Chen Di, veteran of naval command was given control of 6,000 marine fighter and tasked with retaking Tianjin. Chen Di was a master in these affairs and would manage to land and launched a night attack into Tianjin and defeat its forces, slaying Gan Hu while he lay sleep in the mayoral mansion. Fei Zang would resist and fight back, but be driven out of the city, retreating into the countryside where he would continue a shoddy resistance. Tianjin secured provided fear for many rebels who surrendered to Qian Qianyi. Leading the forward unit, Mao Wenlong advanced alongside Ligdan Khan, the two smashing into the city of Beijing's Western Gate crushing the brother of the Xingsheng Emperor, Xu Kang, capturing him and then beheading him, carrying his head about as a talisman of victory. The Zingsheng Emperor had already fled west and began resisting, but his quick retreat would be beckoned by pressure from the advance force of Man Gui and Li Kezhou, who were sent with purpose of capturing the false emperor.

The experienced Northern Pacific Cavalry units, 1614

In the next month however more war would be fought that would last throughout 1614 as the real war would begin, a protracted conflict. Man Gui and his forces were taksed with subduing the White Lotus sect in Yanzhili, while Mao Wenlong was dispatched to capture Jinan from the Western Rebels.

Mao Wenlong's Jinan campaign would see success as Qian Shizhen orderly fell back to Kaifeng and defended what was termed the Gansu-Shaanxi-Henan line, holding the variious important sections of the Yellow River. Mao Wenlong however would not press any further, securing Jinan and driving out the bandits along the coastal roads to Shandong. Afterwards, Chen Di would secure the surrender of Fei Zang, who swore to surrender and serve as a supporter of the righteous heaven, a proposal accepted by Chen Di who hoped to quell rebellion in and around the areas of Tianjin and along the coast with benevolence. Qian Shizhen would thence return to Kaifeng and consolidate his position in Henan, Shaanxi and Gansu.

In the western section of Yanzhili, Man Gui and Li Kezhou attacked the Xingsheng Emperor with elite cavalry forces. The Xingsheng Emperor resisted mightily but the disruption in his army caused by the lightning strikes by his foes would destroy his abiity to resist, meanwhile his brother Xu Min fled into Shanxi with much of the army, leaving him to his fate. The Xingsheng Emperor would be slain while fleeing west by a cavalry force under Man Gui, who took the head of the rebel emperor and took it to the Wanli Emperor and gave it as an offering to the God and Ancestorial Spirit, Guan Yu, after which the body was burned and the head placed on display in the next months upon the wall of the Forbidden Palace alongside 77 other heads of the various commandants, captains and leading monks of the Sensing Incense Sect, all displaying total victory of the Ming Empire over the Smelling Incense Sect. In the following year of 1615, war would not come in a substantial form to Yanzhili and instead the Ming government would focus on pursuing its other numerous threats in the other provinces and fronts of war.

Ming provincial infantrymen

The War in Shenxi

The Shenxi Province of the Great Ming was one of the most populous and yet troubled regions in the whole of the empire. Wracked by disasters, the region came to be dominated by roving bandits, primarily mutineer soldiers from nearby garrisons and or from the haphazardly formed armies of the Great Ming dispatched on missions across the north of China. Xue Wenzhou, who served as governor of Shenxi received the role in 1613 and arrived in Taiyuan to a province on the brink of collapse, as bandits traversed the land and dominated the countryside, and the urban population of Taiyuan and other cities remained corrupt with local notables taxing the population beyond their means. Xue Wenzhou was long a non-partisan in the Imperial Court at Beijing and had been friendly with both eunuchs and Donglin doctrinaires, and had gained thus a reputation for his diplomacy and his upright values. As a result of his reputation and also perhaps as a way to diminish his potential power in the capitol, Wei Zhongxian appointed Xue Wenzhou as governor in Shenxi, a task he felt to be impossible and would trend towards the death of this competent force in the court political scene.

Xue Wenzho entered position in Taiyuan and prior to any operation suffered news of rebellion by a Buddhist monk named Wang Bin, who rose the banner to kill bandits and promoting enlightenment. Wang Bin had not officially suggested rebellion against the Central Court, but instead stated that he seeks to serve the government and fight bandits, thereby creating a militia force. While initially innocuous, Wang Bin and his forces would refuse to pay taxes and thereby cause strife in the area, creating a complex scene. Xue Wenzhou was at odds to solve the problem and in 1614, he spent most of his time subduing the city of Taiyuan wherein he implemented the strict punishments upon corruption, acting in accordance with state policy. Appointing loyal and righteous men to posts as surveillance officer, patrol captain, deputy of punishments, and prison warden, a program of centralization and anti-corruption occurred in Taiyuan under Xue Wenzhou. The countryside however was aflame with conflict as bandits fought bandits, and the White Lotus rebels fought bandits, and the garrisoned soldiers remained fearful and or focused on the war in the capitol province. Xue Wenzhou for his part promoted a defense of Taiyuan and of throughways, creating a regular patrol along the roads connecting major areas and dispatching garrisons to the forts to defend against onslaught from the Western Pacific Army and its commanders who remained in Shaanxi.

War in Shenxi however would shift dramatically with the events to the south and east. Yi Jung, the former bandit and guard commander of Luoyang fled north into Shenxi without even engaging Qian Qizhen, reorienting himself once again as a bandit, but now with a well armed force of fighters. Yi Jung entered Shenxi and began feuding with many of the local bandits, defeating them quickly and uniting them under his banner, all the while feuding with the local governor Xue Wenzhou the White Lotus Rebels that remained led by Xu Min, and against Wang Bin. Yi Jung by the end of 1614 was the strongest power in southern Shenxi, capturing many areas in the south and in the winter of 1615, slew Xu Min, the last known brother of the late Xingsheng Emperor of the Sensing Incense Sect. Wang Bin and Yi Jung however would come to blows just south of Taiyuan with the forces of Yi Jung acquiring the advantage in most skirmishes.

Yi Jung drove Wang Bin northward and slew many of the chief White Lotus rebels in the areas south of Taiyuan, but began taking taxes from the people of southern Shenxi. Brutalizing the locals Yi Jung created from himself a domain across the south of Shenxi, accumulating many bandit subordinates and friendly militia that pledged allegiance to him, leading to him being referred to as the 'Bandit King of Shenxi' and sometimes called informally, King Wei. Wang Bin and his rebels began to view Yi Jung as a chief rival, not only for his position as a powerful military force in Shenxi, but also due to his taxation of the public and brutal displays of authority that went strongly against the ideals of Wang Bin and his supposed enlightened militia. Xue Wenzhou for his part lacked the military forces to combat Yi Jung and instead hoped to receive aid from the central government forces, which arrived in the form of Li Kezhou and his 6,000 Jurchen force.

Li Kezhou was just as corrupt and malignant to the population as that of YI Jung, and whence he arrived, his efforts were to immediately suppress the locals in eastern and northern Shenxi, looting them for goods. Receiving the task of suppressing the Sensing Incense Sect and the Buddhist rebels, he saw an ally in other bandits in the region. Not wishing to exert his own force, he dispatched word to legitimize Yi Jung, requesting that Xue Wenzhou support his effort and surrender his funds to aid in the appeasement of Yi Jung. Xue Wenzhou responded with a stern refusal, causing a major disagreement between the two forces. All would come to a head in the summer of 1615, when the forces of Li Kezhou marched in effort to join with Yi Jung in attacking Wang Bin, were ambushed by the patrol officers serving under Xue Wenzhou and Wang Bin, defeating the Jurchen force in the hill country, killing around 1,000 fighters and capturing Li Kezhou, who was thence beheaded. Xue Wenzhou would then send a envoy to the capitol regaling the Chief Eunuch and Imperial Court on the whole affair, causing a new Shenxi crisis to emerge. For the rest of 1615, Xue Wenzhou would turn his support to Wang Bin and fight Yi Jung, with Shenxi coming to be divided between the two to three factions, while the west of Shenxi remained untouched, the south, central and east became the scene of frequent conflict.

Western Pacific heavy lancers, so-called Orange Dragon Units

The War in Shaanxi, Sichuan, and the Great Dzungar

While Qian Shizhen marched east to battle for supremacy, his sub-commanders waged war in the west of the empire. Zhao Shujie, the so-called Left Commander, was taksed with capturing the city of Xi'an, defended by Boyue An, the Tri-Sided Guard, the defacto governor of Shaanxi-Gansu. Boyue An ha woefully undersupplied to defend the city due to reliance on the Western Pacific Army in previous years for defense. Eve the 30,000 strong force led by Zhao Shujie would be too much for the beleaguered Boyue An and his 6,000 strong garrison, mostly conscripted in rapid succession to defend the city. Boyue An instead relied on support from the Sichuan province to the south, led by Wu Yongxia.

Wu Yongxia was a commanding scholar in Beijing for many years prior to his service as governor of Sichuan and had been what was called an Imperial Absolutist, believing in the primacy of the Household Ministry over that of the other ministries of the state. Therefore, Wu Yongxia was noted for this keen support from and for the Eunuchs in the palace in favor of the Wanli Emperor and for King Fu against the more doctrinaire Confucians of the Donglin Faction. Command in Sichuan was a shrewd move by Wei Zhongxian to control the influx of food and soldiers into the Western Pacific Army and therefore Sichuan was a key factor in deterring the power of military cadres in the western provinces and Wu Yongxia would remain stalwartly in favor of his powerful patron in Beijing.

Wu Yongxia under advice from his anti-Donglin patrol officer and surveillance director, Ji Kui, dispatched a force of 30,000 militia and patrol fighters under Ji Kui to relieve the siege of Xi'an. Under the banner of 'Suppressing Mutineers,' the Sichuan force progressed rapidly, receiving the submission of Wudu and several prefectures between Gansu-Shaanxi and that of Sichuan. Ji Kui was a confident fighter who felt himself readied to face Zhao Shujie, however, mistaken numbers had reached Sichuan, giving the impression that the forces of Boyue An were larger than they were. Reasons for this lied in the fact that the Sichuan assumed that the full allotted 20,000 soldiers of the Tri-Sided Brigade were stationed in Xi'an and readied for war. However, unbeknownst to Wu Yongxia and his supporters, the Tri-Sided Brigade had been dispatched on missions to the frontier against military command and afterward isolated and then its captains defected alongside Qian Qizhen and remained station on the frontier fighting the Ngolok raiders in alliance with the Dzungar. As a result of the mistakes, the forces of Ji Kui marched confidently into a death trap.

Ji Kui and his forces would be decisively defeated by Zhao Shujie and driven from the field near Xi'an. Boyue An would resist for another week before surrendering in late 1614, giving his seal, officially transferring Xi'an and the whole of Shaanxi-Gansu to the Western Pacific Army. With the position secured in the Shaanxi secured, Qian Qizhen settled into Xi'an, commanding the province as his new HQ, a defensible position to wage war. Xi'an was defended both to the west, north and east, but its one weakness lied in the south. where Sichuan held key passes into the valley surrounding the city. Qian Qizhen therefore focused on suppressing the threat to the south found in Sichuan. Qian Qizhen thus dispatched Ma Shilong, a young Hui Muslim captain with 7,000 Hui fighters to harass Ji Kui.

Western Pacific Soldiers assault the area around Wudu, 1615

In the lands of the Great Dzungar, the peace with the Great Ming had brought tangible benefits in the form of trade of horses and of precious goods needed for the horde. Peace and prosperity on the eastern frontier would allow a stability to formulate that would benefit the Great Dzungar as a whole. In Mongolia, the Dzungar also began reiterating a new peace with the neighbors, trading with their enemy Abasi Khan, granting him new weapons to fight against his foe, the Manchu and their supported viceroy, Noyan Khan. Sariparabhuta, the Maharaja and so-called Wheel Turning King of the Dzungar however continued to face resistance to his south in relation to the dispute between the various sects of the Vajrayana Buddhist faith and the constant raids enacted by the Ngolok. The Chakravartin would focus his first attention on war with the the Amdo Mongols who ran rampant across the region to the east of Lhasa and a rearguard force was sent to suppress Ngolok raids.

The Dzungar attempts to subdue their foes would be fret with issues as the Amdo Mongols resisted mightily in their hills, making the war fearsome and fruitless in the first years. In the Ngolok areas, the raiders continued to harm the trade routes, but consistent defense by the nomadic warriors in patrol would reduce risk. Ming forces also under the command of Hu Tang would raid the Ngolok and reduce the risks of attacks. The cooperation between the Dzungar and the Ming would only help in reducing the threats of the Ngolok on both powers. The uneasy peace between the Ming and the Dzungar would continue into 1616, as the Dzungar supported the Western Pacific Army both financially and in the form of material soldiers who joined the ranks of the Western Armies regularly.

Another avenue for support for the Western Pacific Army would be the local population of Gansu and Ningxia, prefectures under the overall Shaanxi province. This province at the edge of the Ming Empire had become known as an unique mixture of cultures, both Turkic, Mongol, Tangut, Chinese, and was a broad mixture of religions. Gansu was the western outpost of the wider Donglin Movement, with doctrinaire Confucianism finding a fertile ground in the region due to state settlement programs issued by the Great Ming government. The Confucian gentry made their life in the Gansu supporting the Western Pacific Army and regarded Qian Qizhen as a 'Patron of Heaven' and as 'Guarantor of Sagely Wisdom.' Support fromt he Confucian gentry afforded the Western Pacific Army a great resource, both in tax base, but also in local governance, as the officials supported the army without much issue. Similarly, the Hui Muslim population, largest in Gansu and Ningxia, supported the Western Pacific Army with a near absolute quality of loyalty. Many Hui served under Qian Qizhen and were highly valued by the general and Uyghurs who had migrated into the region and practiced Sunni Islam supported the general and his designs within the Empire. Muslim and Confucian support for the Western Pacific Army would ensure a kind of dominance in the furthest western provinces that ensured Qian Qizhen could, under right circumstances, maintain a protracted war against Wei Zhongxian.

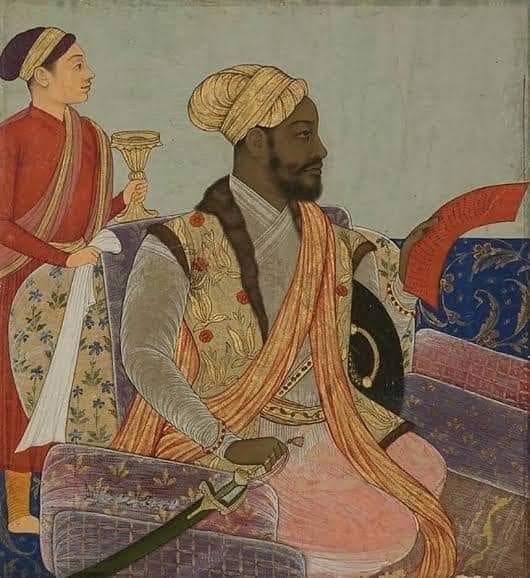

Great Viet Commander Wu Jinzhi

The Wars and Problems in the South

Yuan Chonghuan would be rewarded with honors by the Six Ministries. A paragon of virtue, Yuan Chonghuan was an upright general who hoped for the victory of the dynasty over all evil and sought to crush out enemies of Heaven. More importantly however, Yuan Chonghuan promoted benevolence in leading his army, paying the soldiers well, administering fair punishments and being generous to the commoners. His actions would lead to the public calling him 'Righteous Guard of Chu.' Other bandit riots would erupt in the lands of Chu and Wu, but would be swiftly suppressed by the various guards, especially by Yuan Chonghuan, who issued a policy of crushing rebels with a mixed effort of military shock and benefits of amnesty. Threats to the Great Ming would emerge not in the lands of Chu and Wu however, but in the land of Yue or better yet spelled, Viet.

Having quelled the Mac rebels, supported once by the Great Ming, the Great Viet (Yue to the Chinese) issued a declaration to remediate the situation in the northern provinces. Claiming to be restoring the correct appointments in the provinces to its immediate north, the Honding Emperor issued a decree to 'Pacify Banits, Cultivate Civility' and 'Appointing Prefects, Reminding Boundaries,' thereby declaring a war against the Great Ming Empire. For several years the issues on the border had been brewing for conflict as Mac rebels often fled into the Great Ming provinces of Guangxi and Guangdong, seeking refuge from the local governors. Dispatching a general named Wu Jinzhi to strike the Great Ming, the Viet Court at Dongkin, hoped for a speedy campaign to ensure the repatriation of the 'northern provinces' into the 'close orbit' of the celestial majesty. Leading upwards of 60,000 fighters, Wu Jinzhi marched through Mon Cai, and attacked the border sentries knonw as the Fangcheng Guard, commanded by Jing Yao. Jing Yao defended valiantly with his force of 7,000, but would be driven forth quickly by the Viet offensive, to which the various guard units in the region began reacting to. Cai Fuyi, the grizzled veteran governor of Guangdong dispatched envoy to Nanjing and Beijing requesting support in the Summer of 1614, but the wars emerging in the north would limit the effects of these overtures.

Wu Jinzhi drove out the forces of Jing Yao and would thence divide into two command forces that then pacified various areas on the way to Qizhou, the main target of Viet strikes. Fangcheng would provide a fearsome defense against the Viet, as Jing Yao and a force of 600 Spanish would hold out mightily with fearsome canons firing against the enemy. Viet forces however would capture the city after a three month long siege before progressing to Qizhou which would repel the attackers, leading to a back and forth skirmish zone along the southern coast in which the Viet initially held advantage. In the northern part of the battles, the Viet would attack along the Zuo River, targetting first Pingdao and then Nanning. Pingdao would fall with expedition, as the Viet forces lloted the city mercilessly, however the luck of the Viet would be crushed at the Battle of Zuofu, when the Zhuang-Ming commander and notable, Cen Liang with a mixed force of Han and Zhuang would defeat the Viet force in the field and secure a defensive position along the Zuo River.

On the home front, the Viet would continue its isolation policy, expelling all foreigners and banning all Chinese goods entering the country. The Hongding Emperor issued decree after decree suggesting the evil of the 'Ngo Bandits' and outlining the evil of the 'Zhu' family and its evils enacted upon Heaven. All of these efforts would lead to a movement in Dongkin of effigy burning, wherein the populace would set aflame effigies of Chinese goods and icons, with the statement of 'Killing the Foreign to Appease Heaven.' The anti-foreigner vitriol would compliment a policy of Confucian flourishing within the Viet heartlands, as the Hongding Emperor dispatched funds to found academies to teach the classics and disseminate knowledge of heavenly wisdom. Other infrastructure works would also be started, but few things would be finished, as many of the funds were found to be lacking for the actual activities and instead the funds were funneled into building ancestral shrines that were meant to appease heaven, ancestors, and places to pray in preparation for marching north. These trends led to a new literary culture of poems that discussed the deeds of soldiers traveling north, often composed in the local vernacular as opposed to the Chinese tongue used by the state and officials.

Further north, Peng Yingjie continued to support the Dutch and the Pirate King of Taiwan. Opium proliferated into Fujian province from the Dutch sources, granting some wealth to the Dutch merchants, while the opiates spread about the Fujian province, becoming a more popular item than in previous years. Little change would be seen in the rest of China despite the new influx of opium and the wars ongoing, with the center between the Yangtze and Guangdong dealing with a repairing of the Yangtze flood damage under Lin Yudong, whose efforts to clear damage saw the creation of corvee teams that hoped to prepare the way for a more orderly irrigation construction to aid in the periodical floods of the Yangtze.

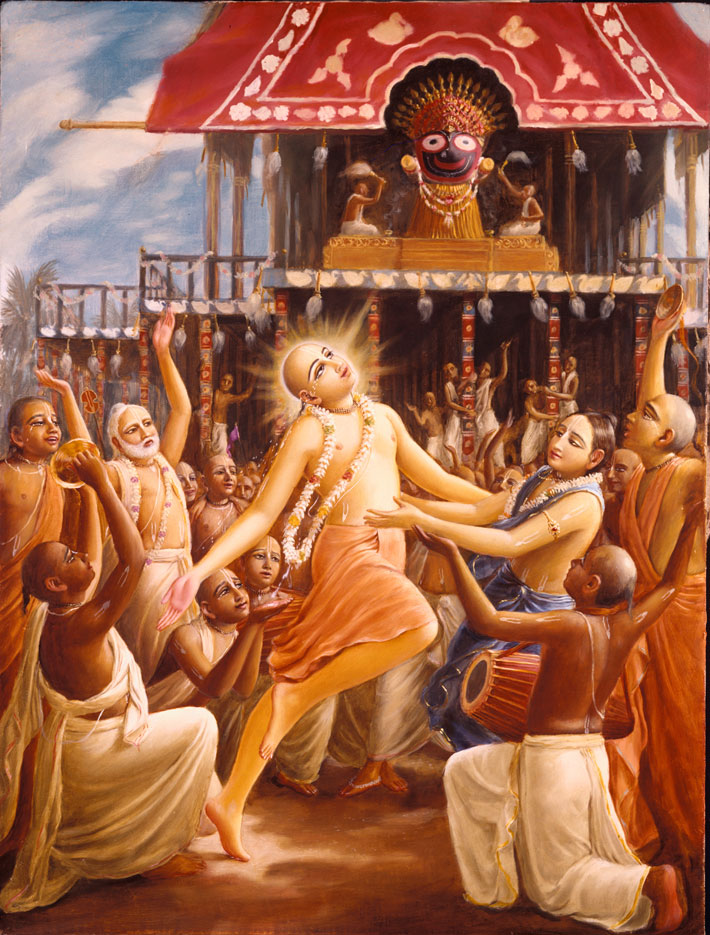

Celebrating the Birthday of King Yeongcheong, 1615

Affairs of Korea & the Manchu, and Mongols

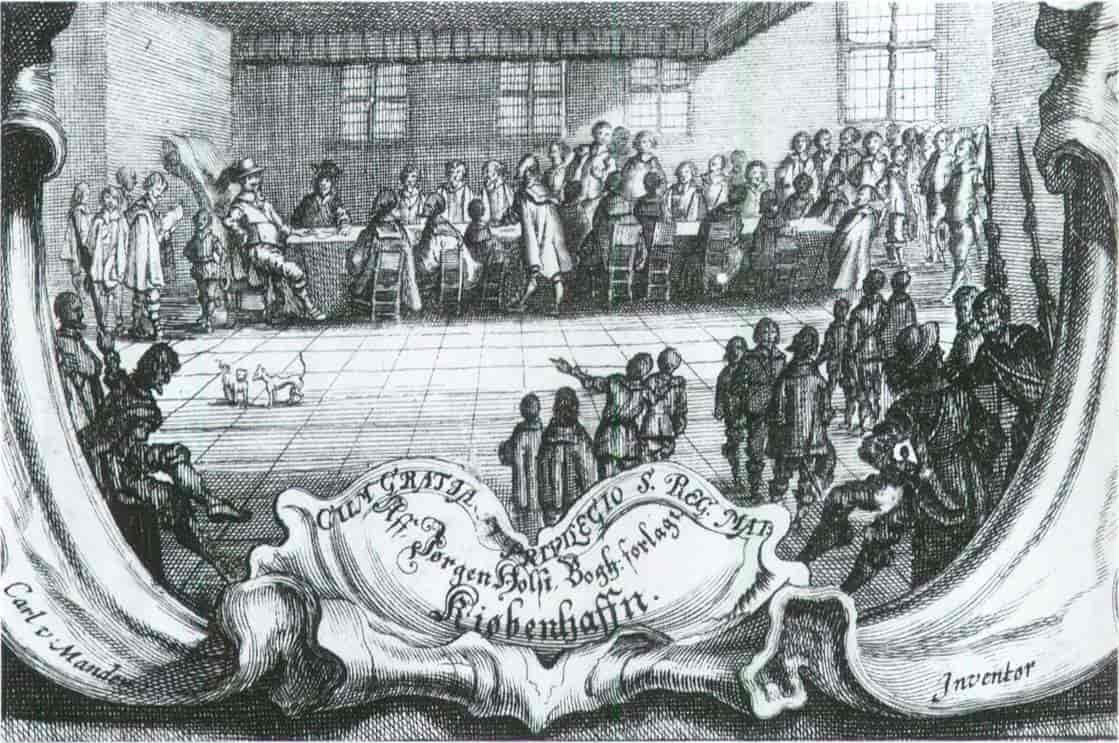

Peace with the Great Ming opened many opportunities for the Manchu, especially as the Great Ming were embroiled in warfare. Manchu horses, fur pelts, and wild game became more prized and the goods flowed into the Ming through horse markets, allowing the Northern Pacific Army to replenish itself more fully and for the Manchu to gain better access to foodstuff. Foodstuff acquired by the Manchu would be used in the settlement programs of Nurhaci, wherein Han Chinese from Liaodong were settled into Manchuria and registered as Bannermen and given honorary names in the Manchu tongue. The influx of new Han who were thence settled as farmers, granted tax holidays, quickly increased the population of the Manchu on the borderzone, and solidified their positive impression amongst the Chinese peoples residing in the northern provinces. Wei Zhongxian for his part hoped to continue the situation with the Manchu, sending them regular congratulatory notices and memorials in favor of the Confucian adherence shown by Nurhaci and his Princes.

Queen Inmok

In the Kingdom of Joseon in Korea, the country would have little change from prior years as the status quo remained. However, the young adolescent King Yeongcheong was being tutored in the ways of kingship by his regency. The new curricular would be referred to as the 'Four Styles' and would involve the King Yeongcheong receiving expert learning based upon the current season, with the four styles education lasting until he reached the end of his regency led by Queen Inmok and by Chief Eunuch Gi Yu.

Winter style was the period of time in which the young king studied the Confucian Classics. Gi Yu, an adherent of Mahayana Buddhism and a firm believer in Buddhist thoughts generally suppressed doctrinaire Confucianism, and instead promoted a moderated Confucianism which asserted a kind of sage-buddha spirit seen in the Song period Buddhism. Confucianism was seen thus as a part of Buddhist philosophy and therefore the two were inseparable. Teachers brought into the king's offices to tutor were ostensibly arguing for the notion that 'two ways, two lands' was the case, wherein the same idea was developed in India as in China. In the Spring, the second style, of war and combat were learned. Promoting the classical methods of combat, the king learned the art of mounted archery and of swordsmanship and the chief skill, riding. These exercised remained more or less rudimentary and focused on style more than utility. Coming into the Summer, the king entered education with Buddhist monks in the temples, travelling weekly to pray and learn the mantras. There, the king learned the mantras and the ways of Mahayana, and the rites by which the 'wheel kept turning.' By 1616, King Yeongcheong was called the 'Wheel Turning King' and given much praise by the temples and monastics. Finally, in the Fall, the king engaged in the last and most important practice, farming, going into the gardens of the monks of the city and collecting the plants for harvest and using them for rituals, fulfilling the duties of a sage king, renewing the rituals of the Yi and Sui.

Efforts to expand the population of Joseon would also be embarked upon, but the efforts would fail as many would not seek to travel so far and instead preferred the Manchu. Lacking the same hostile mountain and rivers to cross, the Chinese of Liaodong remained in their areas or moved into Manchuria, seeking the support of Nurhaci. A Jesuit missionary named Leonardo Casi arrived in Seoul and was summarily captured and thrown into the ocean after being smacked in the head. The authorities thence reported that the man had fallen on accident into the ocean and perished.

Affairs of Japan

With the change of the Era in Japan to the Yuanhe Era, the Tokugawa Shogunate solidified its power further. Tokugawa Hidetada ruled supremely during the third, fourth, and fifth years of Yuanhe. Japan had been more or less subdued and the country prospered under a stable and idealized command of the Shogun. In 1615, or the fourth year of Yuanhe, the former Shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu died after serving in retirement and oddly, in short succession at the start of the fifth year of Yuanhe, the former Tokuyu Emperor, perished and was given the Temple Name of Go-Yozei and interred in Kyoto. The reigning Yuanhe Emperor contented himself with his Tokugawa masters issuing no statements on any affair and instead focused his efforts on poetry, leisure and in holding ceremonial courts based around types of tea and debating the strength of different teas.

@Vitalian , @ZealousThoughts , @Cloud Strife , @DarkLordSauron , @rudy2d , @Zincvit , @Fancy Face , @Tyrell , @Red Robyn

Last edited:

-four-portraits-of-shiaimams,-including-a-certain-imam-ali-naqi-(4-works).jpg)