- Location

- Russia

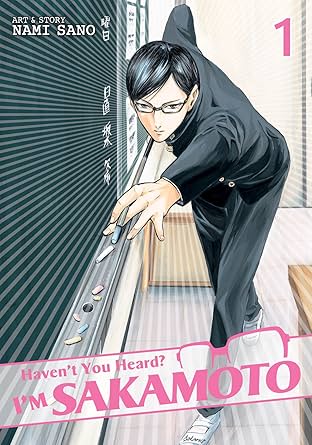

That reminds me of Souji Tendou, heh. A man who is so good at absolutely everything that ultimately, his only fault is that he is incredibly prideful of himself, but even that is mitigated because he is, ultimately, right in that he is nearly perfect when compared to others.The first of those things is entirely dependent on how many characters there are in the story, and in what roles.

The second, likewise, is totally story dependent. A story about a character doing the one thing that they're best at would be sue-ish by your definition.

"No flaws whatsoever" does not make a character sympathetic. It makes them unrelatable and alien.

And Kabuto ended up portraying him as an arrogant, definitely somewhat alien man who is more of a force of nature than a character, and the true protagonist is the person who ends up character-developing off of him.