ByzantineCaesar

Tribune of the Plebs

- Location

- São Paulo, SP, Brazil

THE COSMIC TOUR

Part IV: Das Deutsche Rom

Salzburg, by the time Cosimo Ferdinando de' Medici came by in 1742, had long been one of the premier seats of power of the Catholic Church north of the Alps. Independently ruled since the Middle Ages by its powerful Prince-Archbishops, who had grown fat and wealthy from the local salt works and the salt trade (hence the name of their city, Salzburg), their ecclesiastical state and rank had slowly grown in prominence as it remained a bastion of the Church throughout the Reformation. When Magdeburg fell away from the light of Rome, the Archbishops of Salzburg were made Primates of Germany in 1529. Salzburg alternated with Austria and Burgundy for the presidency of the Bench of Ecclesiastical Princes at the imperial diet in Regensburg, and with the Austrians as director of the entire College of Princes. In the early eighteenth century, the Archdiocese of Salzburg counted with seven suffragan bishops: three imperial (Passau, Freising and Brixen), three in Carinthia and Styria (Seckau, Lavant and Gurk), and Chiemsee in Bavaria. Much valued by the Vatican, the archbishops of Salzburg not only held the title of Primas Germaniae, as the Pope's first correspondent in the German-speaking world, but also that of Legatus Natus ("born legate"), giving them the high honor and privilege of wearing red vesture, even when in Rome. The temporal power of the prince-archbishopric was absolute, while they held immediate pastoral authority over not only Salzburg, but also parts of Bavaria, Upper and Lower Austria, and the Tyrol. Their preeminence was thus unquestionable.

By the mid-eighteenth century, however, Salzburg found itself in relative decline. The transformation of the Holy Roman Empire with the advent of Imperialism had eroded the temporal and spiritual authority of the archbishops, especially after Salzburg was left out of the Harmonious Union in the wake of the War of the Bavarian Succession. The prosperity of the land also found itself under pressure. The salt works in the Salzkammergut, under the direct administration of the archbishops' Hofkammer, remained as prosperous as ever, as did the market towns of the lower valleys, but the situation of the rural economy was less stable. Hidden away on the mountainsides and the high valleys, the bulk of the population was scattered throughout family-sized farmsteads (Guts), rarely coming together to form even villages.

Four out of five of the inhabitants of a Gut were typically safely established, whether due to kinship to the family patriarch or to ownership of the farm estate. The other fifth were less fortunate, however. They were more distant relations, wage or contract laborers and seasonal workers, detached from the core family unit. Overpopulation had thus placed the rural economy under stress, which often expressed itself in the form of religious strife: the towns and markets of the Salzkammergut were firmly Catholic, but the household members of the Guts, who had no need or use of organized religion, were less so. It is said that the Archbishops had been considering expelling the Protestant population, heavily concentrated in the alpine region of Pinzgau and Pongau and numbering well over, at least, thirty thousand, a process to which the War of the Bavarian Succession had put an end to. The House of Medici had been granted the Prince-Archbishopric as a secundogeniture, and in the complicated regime change that followed all plans for mass expulsion had to be scrapped.

By the mid-eighteenth century, however, Salzburg found itself in relative decline. The transformation of the Holy Roman Empire with the advent of Imperialism had eroded the temporal and spiritual authority of the archbishops, especially after Salzburg was left out of the Harmonious Union in the wake of the War of the Bavarian Succession. The prosperity of the land also found itself under pressure. The salt works in the Salzkammergut, under the direct administration of the archbishops' Hofkammer, remained as prosperous as ever, as did the market towns of the lower valleys, but the situation of the rural economy was less stable. Hidden away on the mountainsides and the high valleys, the bulk of the population was scattered throughout family-sized farmsteads (Guts), rarely coming together to form even villages.

Four out of five of the inhabitants of a Gut were typically safely established, whether due to kinship to the family patriarch or to ownership of the farm estate. The other fifth were less fortunate, however. They were more distant relations, wage or contract laborers and seasonal workers, detached from the core family unit. Overpopulation had thus placed the rural economy under stress, which often expressed itself in the form of religious strife: the towns and markets of the Salzkammergut were firmly Catholic, but the household members of the Guts, who had no need or use of organized religion, were less so. It is said that the Archbishops had been considering expelling the Protestant population, heavily concentrated in the alpine region of Pinzgau and Pongau and numbering well over, at least, thirty thousand, a process to which the War of the Bavarian Succession had put an end to. The House of Medici had been granted the Prince-Archbishopric as a secundogeniture, and in the complicated regime change that followed all plans for mass expulsion had to be scrapped.

The Salzburg that welcomed Cosimo IV de' Medici with open arms was not the impoverished Salzburg of the mountainsides and the high valleys, however, but the splendid Salzburg of the archbishops. The wealth of the city, combined with the immaculate vision of its rulers, had made Salzburg into the capital of the German Baroque. By the 1740's, the medieval city was long gone, replaced instead by the churches, palaces, townhouses, gardens and fountains of the new style of the Counter-Reformation. "The music of the bells here is otherworldly," Cosimo would write home, once he had settled in the city. "Every church is an instrument in a symphony, and it is as if all of Salisburgo is an open air opera house. It is no wonder that they call this city the Rome of the North, for beauty like this is difficult to see, even in Italy." The so-called German Rome was indeed a city of churches, although it was not the Cathedral of Saints Rupert and Vergilius that dominated the local skyline, but the ancient castle of the archbishops. Resting on a five hundred meter peak above the Salzach river, the fortress-palace of Hohensalzburg towered over the city, still intimidating in this time and age.

After a long sojourn to the alpine town of Bad Gastein, where the Queen Louise Élisabeth could enjoy the famed healing waters of the mountain hot springs to fully recuperate from her ordeals, the Medici made their entry to the city, escorted by what the Medici did best: great fanfare. They had already passed through Salzburg on the way to Vienna, but the reception then had been dedicated to the Emperor. This time, it was the Medici they celebrated, for the Most Serene King brought with him the new occupant of the archiepiscopal throne. Prince Giuliano Gastone de' Medici was Cosimo IV's third son. He had been born in 1731, the very same year that Salzburg had come into the possession of the House of Medici. Giuliano had been raised from birth for a church career; therefore, he had been raised from birth for Salzburg, and for his very occasion. The prince was only eleven years old, but his election as Archbishop had been predetermined (though not without some concessions, as his father had had to promise the cathedral chapter that his son would not introduce new religious orders to the archdiocese, where the Benedictines held almost complete sway). Therefore, following the Duke of Urbino's resignation from the see, his godson Giuliano Gastone was elected the new Archbishop of Salzburg, while the Medici rested in Bad Gastein.

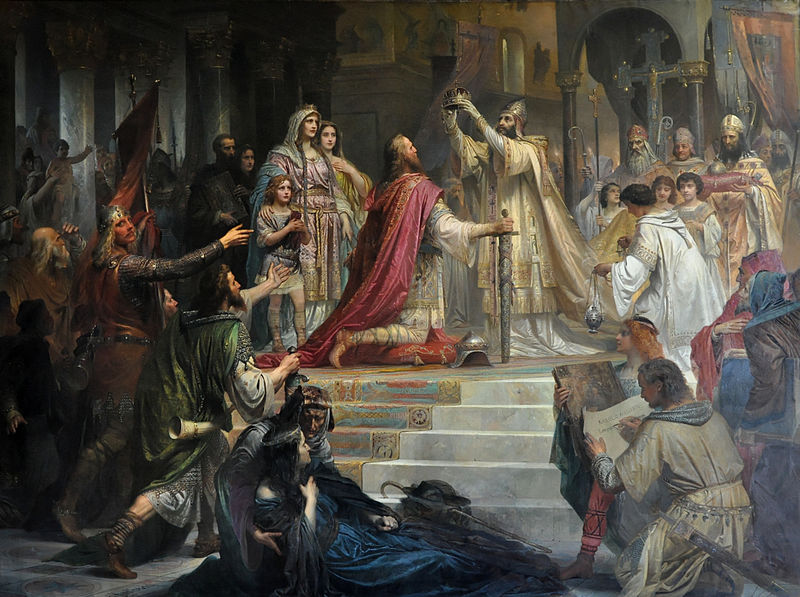

The next month, as was the tradition, the new Archbishop made his triumphal entry to the city. Cosimo IV records his amusement at the situation in his diary, as, even though he held precedence over his son due to being a King, his eleven year old son had been the center of attention. It was understandable. Salzburg had been left adrift since 1731, with the Cardinal de' Medici, the nominal archbishop, treating it with utmost neglect as a mere source of income and station, having never even visited his see. The Salzburgers, then, embraced the new archbishop with great enthusiasm, hoping that better times for their state were in sight. Salzburg received the Medici with pomp and circumstance, as befitting the enthronement of their new sovereign. To the sound of drums, trumpets, bells and two hundred cannons, which added to the joyous chorus from atop the Hohensalzburg fortress, a procession of the members of the archiepiscopal court, the estates and the guilds escorted the Medici to the Domplatz, the cathedral square, where the citizens paid the young prince their homage to the cries of "Vivat Julian Gaston, our prince and lord!", cries of jubilation which persisted well into the night. At age eleven, Giuliano Gastone de' Medici was enthroned as Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg. Although he would only take his religious vows and properly assume ecclesiastical functions once he came of age, he was promoted as Cardinal in a consistory held by Pope Innocent XIV two months later.

After a long sojourn to the alpine town of Bad Gastein, where the Queen Louise Élisabeth could enjoy the famed healing waters of the mountain hot springs to fully recuperate from her ordeals, the Medici made their entry to the city, escorted by what the Medici did best: great fanfare. They had already passed through Salzburg on the way to Vienna, but the reception then had been dedicated to the Emperor. This time, it was the Medici they celebrated, for the Most Serene King brought with him the new occupant of the archiepiscopal throne. Prince Giuliano Gastone de' Medici was Cosimo IV's third son. He had been born in 1731, the very same year that Salzburg had come into the possession of the House of Medici. Giuliano had been raised from birth for a church career; therefore, he had been raised from birth for Salzburg, and for his very occasion. The prince was only eleven years old, but his election as Archbishop had been predetermined (though not without some concessions, as his father had had to promise the cathedral chapter that his son would not introduce new religious orders to the archdiocese, where the Benedictines held almost complete sway). Therefore, following the Duke of Urbino's resignation from the see, his godson Giuliano Gastone was elected the new Archbishop of Salzburg, while the Medici rested in Bad Gastein.

The next month, as was the tradition, the new Archbishop made his triumphal entry to the city. Cosimo IV records his amusement at the situation in his diary, as, even though he held precedence over his son due to being a King, his eleven year old son had been the center of attention. It was understandable. Salzburg had been left adrift since 1731, with the Cardinal de' Medici, the nominal archbishop, treating it with utmost neglect as a mere source of income and station, having never even visited his see. The Salzburgers, then, embraced the new archbishop with great enthusiasm, hoping that better times for their state were in sight. Salzburg received the Medici with pomp and circumstance, as befitting the enthronement of their new sovereign. To the sound of drums, trumpets, bells and two hundred cannons, which added to the joyous chorus from atop the Hohensalzburg fortress, a procession of the members of the archiepiscopal court, the estates and the guilds escorted the Medici to the Domplatz, the cathedral square, where the citizens paid the young prince their homage to the cries of "Vivat Julian Gaston, our prince and lord!", cries of jubilation which persisted well into the night. At age eleven, Giuliano Gastone de' Medici was enthroned as Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg. Although he would only take his religious vows and properly assume ecclesiastical functions once he came of age, he was promoted as Cardinal in a consistory held by Pope Innocent XIV two months later.

GIULIANO GASTONE DE' MEDICI

Cardinal-Archbishop of Salzburg, Primate of Germany and Duke in Bavaria

Change, as a matter of fact, came immediately, delivered to the citizens, guilds and estates of Salzburg by the means of a well-rehearsed address professed by the eleven year old archbishop himself, from the canopied dais in the Domplatz. Giuliano spoke German fluently since infancy, as his father the Most Serene King had insisted on, and, despite a twist of tongue or two due to his youth, the speech the boy read from the script he had been given was the highpoint of the ceremony. The true authorship of the text, as it would later become clear, was his father's, if not in practice, then in essence. Cosimo IV had been brought up on the legend of L'Apertura and the Fernandine Revolution, when his father, King Ferdinand III, had done away with the religious tyranny and obscurantism of his predecessor, Cosimo III, and promoted a reopening of the Tuscan society, science and social life. Cosimo Ferdinando had privately bemoaned that he had not been given a similar chance to shine and inscribe his name in the annals of history. So, when given the opportunity to correct the old regime and the Medicean neglect in Salzburg, who can blame him for acting on it? Certainly not the King himself, who would later proudly take credit, in his correspondence, of having promoted the "Salzburger Eröffnung", i.e. L'Apertura of Salzburg, bringing education, enlightenment and good governance in the image of his father to "das Mutterland," a model of modernity in direct contradiction to the perceived obscurantism of Nuremberg that still held much of the Mutterland under its thumb.

The people of Salzburg, after all, had long lived under a so-called priest and police state. The beating heart of the Counter-Reformation in Germany, the archiepiscopal authorities had spared no expenses, in the past, to enforce social behavior in accordance with their understanding of Catholic virtue and morals. That they made money out of oppressing the population was merely a coincidence. Whilst not as extreme as Cosimo III's state of religious terror had been in Tuscany, the Salzburger version of it could not be disregarded. Serious offences against public decency, such as fornication and adultery, were punished with fines, imprisonment, forced labor and even territorial banishment. For minor offenses, the pillory was frequently used. Fundamental aspects of courtship, such as the practice of a lover's nightly visits before his girl's window, were prohibited, as well as other social practices such as dancing between May and September, the playing of Schmoldern (a roulette-like game), smoking tobacco etc. In short, when not overworked in the salt mines or suffering from the negative consequences of overpopulation in the highlands, the peasantry was faced with a police state ready to squeeze them out of every penny, while urban life in the city proper found itself stifled, and its forms of entertainment strictly controlled. The moralism present in Salzburg's police state was not uncommon elsewhere in the Catholic world, but, Cosimo thought, had already run its course by the 1740's.

The Prince-Archbishop's enthronement speech would directly address many of these issues, announcing measures that were to be taken immediately and laying out plans for the future. The actions and policies of the Salzburger Eröffnung closely mirrored, by no coincidence, the platform of Florence's 1708 L'Apertura, starting with the penal code. Capital punishment was extinguished for all crimes but high treason, differently from L'Apertura, which had allowed the death penalty also for the crimes of lèse-majesté and murder. The former crime would be extinguished in Salzburg, while the latter would receive other punishments, in a telling evolution of neo-humanist views in Tuscan jurisprudence. Public executions were discontinued altogether, as was corporeal punishment for minor offenses. Restrictions on social life were lifted altogether, and fines for improper moral behavior were reduced, when not eliminated. Naturally, many of these measures would be met with opposition and resistance in the established powers of Salzburg, as they significantly decreased the disciplinarian control of the clergy over public and private life, but they would often find popularity with the peasantry, the burghers and the liberal professions, who now found themselves unburdened with the dismantlement of the priest and police state. Such was the introduction of Salzburg to the Tuscan Enlightenment.

The people of Salzburg, after all, had long lived under a so-called priest and police state. The beating heart of the Counter-Reformation in Germany, the archiepiscopal authorities had spared no expenses, in the past, to enforce social behavior in accordance with their understanding of Catholic virtue and morals. That they made money out of oppressing the population was merely a coincidence. Whilst not as extreme as Cosimo III's state of religious terror had been in Tuscany, the Salzburger version of it could not be disregarded. Serious offences against public decency, such as fornication and adultery, were punished with fines, imprisonment, forced labor and even territorial banishment. For minor offenses, the pillory was frequently used. Fundamental aspects of courtship, such as the practice of a lover's nightly visits before his girl's window, were prohibited, as well as other social practices such as dancing between May and September, the playing of Schmoldern (a roulette-like game), smoking tobacco etc. In short, when not overworked in the salt mines or suffering from the negative consequences of overpopulation in the highlands, the peasantry was faced with a police state ready to squeeze them out of every penny, while urban life in the city proper found itself stifled, and its forms of entertainment strictly controlled. The moralism present in Salzburg's police state was not uncommon elsewhere in the Catholic world, but, Cosimo thought, had already run its course by the 1740's.

The Prince-Archbishop's enthronement speech would directly address many of these issues, announcing measures that were to be taken immediately and laying out plans for the future. The actions and policies of the Salzburger Eröffnung closely mirrored, by no coincidence, the platform of Florence's 1708 L'Apertura, starting with the penal code. Capital punishment was extinguished for all crimes but high treason, differently from L'Apertura, which had allowed the death penalty also for the crimes of lèse-majesté and murder. The former crime would be extinguished in Salzburg, while the latter would receive other punishments, in a telling evolution of neo-humanist views in Tuscan jurisprudence. Public executions were discontinued altogether, as was corporeal punishment for minor offenses. Restrictions on social life were lifted altogether, and fines for improper moral behavior were reduced, when not eliminated. Naturally, many of these measures would be met with opposition and resistance in the established powers of Salzburg, as they significantly decreased the disciplinarian control of the clergy over public and private life, but they would often find popularity with the peasantry, the burghers and the liberal professions, who now found themselves unburdened with the dismantlement of the priest and police state. Such was the introduction of Salzburg to the Tuscan Enlightenment.

JOHANN BAPTIST VON ARCO

Count of Arco, Imperial Marshall and Stadtholder of Salzburg

The Italian Enlightenment might have been less well received in Salzburg, had it not found an important pillar of support in a new element that had been introduced after the War of 1731. The clergy and the guilds had long been established powers in Salzburg. A third power, however, had made itself present after the war, namely the group of Bavarian exiles, often accompanied by their families and households, who had taken refuge in Salzburg following the end of the Bruderkrieg (as well as a small company of Jacobite mercenaries, some of whom settled in Salzburg indefinitely). Although a large share of exiles had opted for Vienna instead, many ended up finding their way to neighboring Salzburg, the lands of which closely resembled their former homes in Oberbayern. Their leader was the illustrious Graf von Arco, a celebrated Bavarian general and loyalist who had refused to recognize Heinrich of Habsburg as Elector of Bavaria and, at Violante of Wittelsbach's instigation, had rallied Heinrich's opponents and declared for Cosimo IV as the rightful King and Elector of Bavaria.

Arco had been an old friend of the Medici by then, having fought by Cosimo III's side in the War of the Mantuan Succession and later leading the Bavarian military mission in Tuscany during the reign of Ferdinando III, reforming the Tuscan army to uphold the standards and forms of organization of Maximilian II Emanuel's forces. When the Dowager Queen of Tuscany reached out to the old general twenty years later, calling on him to defend the dynastic rights of the House of Wittelsbach and those of her only son to Bavaria, the Count of Arco had not hesitated. Although Arco and the Duke of Berwick had been unsuccessful in removing Heinrich from Bavaria, they were still richly rewarded for their service. Arco's loyalty and allegiance in particular earned him the governorship of Salzburg, after the war was done. The old general was not the only one to take up Tuscan service in Salzburg. Many of his allies and supporters had chosen exile over suffering the consequences of Heinrich's wrath, fleeing to Salzburg with their wealth, possessions and servants. Together with select Jacobite mercenaries, these exiles had become the bulk of the Salzburg Regiment, watching over the city and the Salzkammergut from the Hohensalzburg garrison to serve as jailers of the Harmonious Union.

Even a decade later, in 1742, many of the Bavarian exiles still recognized His Most Serene Majesty as Kosmas Ferdinand Maximilian of Bavaria, although his claim was long defunct. Moreover, they sought to find their place in the government of Salzburg, jealously guarded by the clergy. Therefore, when their King came to Salzburg and brought with him the Florentine lights, very much the opposite of Nuremberg's mysticism and increasingly aligned to the principle of secular authority over temporal matters, they were quick to offer their support. They were in turn awarded for their loyal service in the form of commissions, pensions and honors, generously distributed among them by both the King of Tuscany and the Cardinal-Archbishop. A final honor, in addition to the many already received in 1731, would be bestowed upon the ailing Arco, with his elevation to the hereditary rank and title of Serene Prince, as a peer of Tuscany and Africa. Now approaching ninety years of age, the now Prinz von Arco would finally personally meet His Most Serene Majesty, offering him a grand reception at the Salzburg Residenz. Cosimo would give him his heartfelt gratitude and finally allow the ancient general to retire, granting him a generous stipend as a pension of the Order of St. Stephen and the use of Mirabell Palace for life. At his recommendation, the prince Johann Aloys zu Oettingen-Spielberg was named as his successor as Stadtholder, with Hieronymus Cristiani von Rall stepping in as Hofkanzler (chancellor). They would be entrusted with the government of Salzburg during their Prince-Archbishop's minority (and perhaps beyond that), as Julian Gaston was expected to return to Italy to receive further education in Florence, Pisa and Rome. With his older sister Diana de Medicis settled down next door as Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Hungary, there was also a reasonable expectation that, in time, the Cardinal-Prince would attend the recently founded Carolean academies and perhaps play a significant role in the governance of Austria.

Arco had been an old friend of the Medici by then, having fought by Cosimo III's side in the War of the Mantuan Succession and later leading the Bavarian military mission in Tuscany during the reign of Ferdinando III, reforming the Tuscan army to uphold the standards and forms of organization of Maximilian II Emanuel's forces. When the Dowager Queen of Tuscany reached out to the old general twenty years later, calling on him to defend the dynastic rights of the House of Wittelsbach and those of her only son to Bavaria, the Count of Arco had not hesitated. Although Arco and the Duke of Berwick had been unsuccessful in removing Heinrich from Bavaria, they were still richly rewarded for their service. Arco's loyalty and allegiance in particular earned him the governorship of Salzburg, after the war was done. The old general was not the only one to take up Tuscan service in Salzburg. Many of his allies and supporters had chosen exile over suffering the consequences of Heinrich's wrath, fleeing to Salzburg with their wealth, possessions and servants. Together with select Jacobite mercenaries, these exiles had become the bulk of the Salzburg Regiment, watching over the city and the Salzkammergut from the Hohensalzburg garrison to serve as jailers of the Harmonious Union.

Even a decade later, in 1742, many of the Bavarian exiles still recognized His Most Serene Majesty as Kosmas Ferdinand Maximilian of Bavaria, although his claim was long defunct. Moreover, they sought to find their place in the government of Salzburg, jealously guarded by the clergy. Therefore, when their King came to Salzburg and brought with him the Florentine lights, very much the opposite of Nuremberg's mysticism and increasingly aligned to the principle of secular authority over temporal matters, they were quick to offer their support. They were in turn awarded for their loyal service in the form of commissions, pensions and honors, generously distributed among them by both the King of Tuscany and the Cardinal-Archbishop. A final honor, in addition to the many already received in 1731, would be bestowed upon the ailing Arco, with his elevation to the hereditary rank and title of Serene Prince, as a peer of Tuscany and Africa. Now approaching ninety years of age, the now Prinz von Arco would finally personally meet His Most Serene Majesty, offering him a grand reception at the Salzburg Residenz. Cosimo would give him his heartfelt gratitude and finally allow the ancient general to retire, granting him a generous stipend as a pension of the Order of St. Stephen and the use of Mirabell Palace for life. At his recommendation, the prince Johann Aloys zu Oettingen-Spielberg was named as his successor as Stadtholder, with Hieronymus Cristiani von Rall stepping in as Hofkanzler (chancellor). They would be entrusted with the government of Salzburg during their Prince-Archbishop's minority (and perhaps beyond that), as Julian Gaston was expected to return to Italy to receive further education in Florence, Pisa and Rome. With his older sister Diana de Medicis settled down next door as Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Hungary, there was also a reasonable expectation that, in time, the Cardinal-Prince would attend the recently founded Carolean academies and perhaps play a significant role in the governance of Austria.

The Salzburg Regiment's parade for the enthronement of Prince Julian Gaston de Medicis before the Residenz

The Medici would linger in Salzburg for a few weeks, enjoying a blissful retirement from the world after the grand festivities for the Triple Wedding in Vienna and Don Carlos' lively entourage, which they had shadowed since Verona. It suited the Most Serene King just fine. The Medici may be masters of pageantry, but Cosimo IV could only take social merriment in small doses, often preferring the peace and quiet of a well-disciplined court or the introspective and dramatic music of the opera house. Not presuming to make use of the Residenz as his dwellings, and finding the Hohensalzburg too dreary, the King settled in Mirabell Palace for the duration of his stay (the Prince of Arco being a more than generous host). The days were spent lazily in Mirabell, with the occasional reception for a notable of Salzburg occasionally thrown in in the name of the Archbishop. The Most Serene King attended mass in the cathedral almost daily, paid visits to the Benedictine University and the other intellectual circles of the city, and enjoyed the many musical talents of the Salzburger court (including a young violinist by the name of Leopold Mozart, a newcomer to the archbishop's court), though these days Cosimo preferred secular operas over liturgical music.

A highpoint of the visit was when the famously peaceful Cosimo was talked into making a show of martial prowess at the behest of Arco and the Prince of Spielberg. Although he was reluctant to embrace the pageantry at first, Cosimo eventually gave in. "These men called upon me to save their homeland as I had saved mine, and were left with bitter exile instead," he wrote to Cardinal Bandini. "Their loyalty must not only be rewarded, but it is also necessary for the preservation of the independence and sovereignty of Salzburg against the vengeful spirits of Nuremberg and the ambitions of the Generalissimo in Vienna."

The King thus mounted a white stallion and clad himself in a gilded black armor, the red Maltese cross bordered by gold of the Order of St. Stephen proudly emblazoned upon his chest, the grand collar of the same order and that of the Golden Fleece hanging around his neck. Upon his majestic wig rested a golden laurel wreath crown, allegedly presented to the King of Africa by the citizenry of Tunis. The arms of Medici and Wittelsbach flew splendidly in the wind, borne by twin standard bearers behind the King. At the Residenzplatz, he was hailed and saluted by the troops not as their sovereign, but as an honored guest of royal rank. "Vivat Kosmas-Ferdinand, König der Toskana und Afrikas," they chanted. "Vivat Kosmas-Ferdinand, Herzog in Bayern!". They took him up to the Hohensalzburg, where the King was given the opportunity to inspect the garrison and the artillery. It was a spectacle made for the benefit of the Bavarian exiles, who had never quite made their peace with the outcome of the war. Their pseudo-acclamation of Cosimo IV as Duke in Bavaria, in accordance with the terms of the 1731 Family Pact, with the King being present in person and surrounded by military pomp and circumstance, would provide them the closure they had been denied ever since Don Carlos and his lieutenants had ordered them to withdraw from Bavaria and cede all their hard-won gains to the usurper in Nuremberg.

A highpoint of the visit was when the famously peaceful Cosimo was talked into making a show of martial prowess at the behest of Arco and the Prince of Spielberg. Although he was reluctant to embrace the pageantry at first, Cosimo eventually gave in. "These men called upon me to save their homeland as I had saved mine, and were left with bitter exile instead," he wrote to Cardinal Bandini. "Their loyalty must not only be rewarded, but it is also necessary for the preservation of the independence and sovereignty of Salzburg against the vengeful spirits of Nuremberg and the ambitions of the Generalissimo in Vienna."

The King thus mounted a white stallion and clad himself in a gilded black armor, the red Maltese cross bordered by gold of the Order of St. Stephen proudly emblazoned upon his chest, the grand collar of the same order and that of the Golden Fleece hanging around his neck. Upon his majestic wig rested a golden laurel wreath crown, allegedly presented to the King of Africa by the citizenry of Tunis. The arms of Medici and Wittelsbach flew splendidly in the wind, borne by twin standard bearers behind the King. At the Residenzplatz, he was hailed and saluted by the troops not as their sovereign, but as an honored guest of royal rank. "Vivat Kosmas-Ferdinand, König der Toskana und Afrikas," they chanted. "Vivat Kosmas-Ferdinand, Herzog in Bayern!". They took him up to the Hohensalzburg, where the King was given the opportunity to inspect the garrison and the artillery. It was a spectacle made for the benefit of the Bavarian exiles, who had never quite made their peace with the outcome of the war. Their pseudo-acclamation of Cosimo IV as Duke in Bavaria, in accordance with the terms of the 1731 Family Pact, with the King being present in person and surrounded by military pomp and circumstance, would provide them the closure they had been denied ever since Don Carlos and his lieutenants had ordered them to withdraw from Bavaria and cede all their hard-won gains to the usurper in Nuremberg.

The grenadier corps of the Salzburg Regiment

The parade of the Salzburg Regiment in his honor elicited an ever increasing sentiment of melancholy in the Most Serene King. Cosimo had been taken with bouts of longing and depression ever since crossing the Alps, as his grief and the memory of his mother still persisted even five years after her death. The more they approached "Das Mutterland," the ancestral Bavarian homeland of his mother's lineage, the more Cosimo became prone to his grief. The festivities at Vienna had been a useful distraction, but they had left Vienna behind. The extended duration of his stay in Salzburg, a stone's throw away from Bavaria and a part of Oberbayern in all but name, was in part born from his need to connect, on a spiritual level, with the Mutterland. His pompous acclamation by the Salzburg Regiment had only worsened the King's emotional state, rather than improving it. Their rest at Salzburg had been intended to build up their strength to cross the Alps back into Italy, by way of Innsbruck and Verona. Now, however, Cosimo, heartsick and melancholy, sought to add another stop in their journey, which had not been planned beforehand: the city of Munich, his mother's home.

It was not a trip to be taken lightly, considering the recent tension between Emperor Heinrich and the Medici over the Hofburg crisis, but, against his better judgment, Cosimo wrote to Nuremberg, announcing his intention to travel to Munich and seeking their support. As he waited for Heinrich's reply, the Most Serene King threw himself into work, as he was wont to do. Leaving the comfort and luxurious trappings of Salzburg, he toured the Salzkammergut, taking in the impoverished conditions of the countryside and the significant share of idle population, lacking both land and employment other than the occasional seasonal work. "I may have found a solution for both our problems and the problems of the Salzkammergut," he wrote to the economist Carlo Ginori back home. A brother-in-law of the prince Bartolomeo Corsini, Grand Chancellor of Tuscany, Ginori was the Governor of Livorno. He was a faithful adherent of the economic school of Siena and owned a famous porcelain factory that had made him rich. Ginori was known, too, as the greatest advocate of Tuscan colonialism, consistently pestering the court for more resources to develop the colony on San Martino and advocating for the purchase of another Caribbean island "to guarantee us direct trade with America, and perhaps to serve as the first necessary step to bigger projects." Cosimo IV saw in the overpopulation of Salzburg a solution for both states: if Salzburger immigration was encouraged, with the permission to establish settlements both in the depopulated Tuscan Maremma and in the Tuscan Caribbean, especially if Ginori's advice was followed, it would both alleviate the demographic pressure in the Salzkammergut and provide Tuscany and the Tuscan Caribbean with sorely needed workforce and settlers. For now, Salzburger immigration remained in the conceptual phase, but it was an idea firmly rooted in the back of the mind of the Most Serene King.

After all, Cosimo would not have much time to dwell on this matter. The Emperor's reply did not take long to arrive. He would accept his coming, in the name of "reconciling those who have caused issues." It was a language that the Most Serene King disliked, but he could have stomached it for the sake of visiting Munich, were it not for Heinrich's other demands. He was to come to Nuremberg to stand before the Emperor's majestic glow and to bow his head. He would be denied access otherwise. To say that the Emperor's reply infuriated Cosimo would be an understatement. Flashbacks to Ruzzini's demands aside, by what right did Heinrich, the Usurper, restrict access to Bavaria to Cosimo, himself a Duke in Bavaria and dynast of the royal house? By what right could he deny a son of Bavaria himself? It was petty, it was absurd, and it was humiliating, in the King's eyes. Although he was not prone to impulsive action, the conditioning of his visit to the Mutterland on a ritualistic submission at Nuremberg pushed him over the edge.

Heinrich did not want him in Bavaria? Fine. "The obscurity of the court of Nuremberg cannot stand the sight of light. I have better places to be," the enraged King commented to a courtier. Plans to return to Florence were scrapped. If he could not see the Mutterland with his own eyes, the Most Serene King would make it a point to visit every court in Europe but that of Heinrich. From Salzburg, the Rome of the North, the Medici would embark on their Cosmic Tour.

It was not a trip to be taken lightly, considering the recent tension between Emperor Heinrich and the Medici over the Hofburg crisis, but, against his better judgment, Cosimo wrote to Nuremberg, announcing his intention to travel to Munich and seeking their support. As he waited for Heinrich's reply, the Most Serene King threw himself into work, as he was wont to do. Leaving the comfort and luxurious trappings of Salzburg, he toured the Salzkammergut, taking in the impoverished conditions of the countryside and the significant share of idle population, lacking both land and employment other than the occasional seasonal work. "I may have found a solution for both our problems and the problems of the Salzkammergut," he wrote to the economist Carlo Ginori back home. A brother-in-law of the prince Bartolomeo Corsini, Grand Chancellor of Tuscany, Ginori was the Governor of Livorno. He was a faithful adherent of the economic school of Siena and owned a famous porcelain factory that had made him rich. Ginori was known, too, as the greatest advocate of Tuscan colonialism, consistently pestering the court for more resources to develop the colony on San Martino and advocating for the purchase of another Caribbean island "to guarantee us direct trade with America, and perhaps to serve as the first necessary step to bigger projects." Cosimo IV saw in the overpopulation of Salzburg a solution for both states: if Salzburger immigration was encouraged, with the permission to establish settlements both in the depopulated Tuscan Maremma and in the Tuscan Caribbean, especially if Ginori's advice was followed, it would both alleviate the demographic pressure in the Salzkammergut and provide Tuscany and the Tuscan Caribbean with sorely needed workforce and settlers. For now, Salzburger immigration remained in the conceptual phase, but it was an idea firmly rooted in the back of the mind of the Most Serene King.

After all, Cosimo would not have much time to dwell on this matter. The Emperor's reply did not take long to arrive. He would accept his coming, in the name of "reconciling those who have caused issues." It was a language that the Most Serene King disliked, but he could have stomached it for the sake of visiting Munich, were it not for Heinrich's other demands. He was to come to Nuremberg to stand before the Emperor's majestic glow and to bow his head. He would be denied access otherwise. To say that the Emperor's reply infuriated Cosimo would be an understatement. Flashbacks to Ruzzini's demands aside, by what right did Heinrich, the Usurper, restrict access to Bavaria to Cosimo, himself a Duke in Bavaria and dynast of the royal house? By what right could he deny a son of Bavaria himself? It was petty, it was absurd, and it was humiliating, in the King's eyes. Although he was not prone to impulsive action, the conditioning of his visit to the Mutterland on a ritualistic submission at Nuremberg pushed him over the edge.

Heinrich did not want him in Bavaria? Fine. "The obscurity of the court of Nuremberg cannot stand the sight of light. I have better places to be," the enraged King commented to a courtier. Plans to return to Florence were scrapped. If he could not see the Mutterland with his own eyes, the Most Serene King would make it a point to visit every court in Europe but that of Heinrich. From Salzburg, the Rome of the North, the Medici would embark on their Cosmic Tour.

View of Salzburg

Last edited: