Background

inquisition

Not Affiliated With the Spanish Church

- Location

- Valkenheim

The Cause of Humanity: A Communist America HoI IV Let's Play

By Inquisition

Earl Russell Browder, Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the Revolutionary Union of America and General-Secretary of the All-Union Communist Party

By Inquisition

Earl Russell Browder, Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the Revolutionary Union of America and General-Secretary of the All-Union Communist Party

The following backstory is an attempted (and rather flimsy) justification for the ingame ability to assign a major Communist Party leader to an important position in the US government. As an aficionado of alternate history, I acknowledge that this scenario is exceedingly unlikely to have played out as I outline it, and apologize in advance for any histoRAEG this LP may cause.

I will be playing on Regular, with the historical AI focus turned off.

I am using the following cosmetic mods for this playthrough:

I am using the following cosmetic mods for this playthrough:

- Sabas Historical Country Names: Not all of these are the best (the author's love for putting "empire" at the end of almost every alt-fascist, or, in italy's case, historical name is a bit irksome), but for the most part the names are an improvement over the vanilla. Especially important for this LP is the fact that it's the only mod I've found that doesn't use "United Socialist States of America" to replace the "Communist States of America." In other cases, I would recommend Better Country Names.

- Flavor Names Extended: Adds some names to some support weapons that were sadly missing them in-game. No more bombarding enemies with Interwar ArtilleryTM!

- More Division Icons: Pretty self-explanatory, gives some nice new icons to expand division customization a bit.

- Coloured Buttons: Just makes the UI look a little better, at least in my opinion.

- World Press Mod (New York Times for democracy and Daily Worker for communism): A nice little mod that adds new letterheads for the in-game "news reports." Unfortunately, as the mod's creator has been unable to find a way to make the newspapers work depending on your ideology, only one can be active at a time, so I'll have to swap them out manually once the revolution actually goes through.

- A smattering of music packs, including Soviet, Japanese, American, and German period music, as well as a national anthems pack.

Excerpts from A History of America's Communist Century, by Karla Scheele, Professor of History, University of Zurich (2014; translated from the original German)

Preface

Contemporary American political rhetoric paints the Second Civil War (known there as the People's Revolution) as an inevitability, the sure result of 150 years of mercantilism and capitalism and the culmination of Marx's theories on the rise and fall of capital's hegemony over the country. However, once one looks past the propaganda and the rhetoric and looks for the true facts of the fall of what American historians call the "Second Republic," it becomes evident that this is simply untrue. While, as we discussed in the last chapter, the Great War played a major role in the radicalization of the American populace and military, the truth is that none of the following events were set in stone. In truth, the dice fell so perfectly for the American leftist movement in the 1930s that some have described the Second Civil War as an act of intervention from a higher power.

Still, whatever your views on the Revolution and its origins, it cannot be denied that it had far-reaching effects on world events up until this day. The Revolutionary Union of America, the new nation that arose from the ashes of the civil war, would play a major role in the great world conflict that was to come.

[...]

Chapter 2: Peace and Depression (1919-1936)

[...] The 1932 Congressional elections turned out to be more contested than they had any right to be. Given the almost universal revilement of President Hoover and the stigma it attached to the Republicans, expectations were high that the GOP would suffer cataclysmic losses to the Democrats. While this did come true, to an extent—the Republicans would lose their slight majority, dropping down from 218 seats to 183—some of this was to the benefit of the nascent Farmer Labor Party (going up from 1 to 4 seats, all at the GOP's expense) and, for the first time in US history, the Socialist Party of America (gaining 1 Illinois House seat), and while it did give the Democrats a majority, it was not large enough to assuage some of the fears of the Bourbon wing of the party.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 32nd and final President of the United States

This division would prove to be a major hindrance for the incoming President. It has been said that, had Roosevelt possessed more political capital at the start of his first term, he and his allies in Congress could have forced through a number of programs that he had promised during the campaign. However, as a number of right-wing Democrats were unwilling to risk their re-elections for what many saw as needless spending and worthless bluster, a number of cruical measures were either neutered on the legislative floor or were simply not enacted. Roosevelt can be credited for doing his best in the face of Congressional opposition, but public opinion in a democracy can be a fickle thing--voters, on the whole, like to see results rather than effort. As a result, the establishment took a number of heavy blows during the early 1930s.

Into this new, fracturing political scene stepped a number of more fringe groups, the most mainstream of which was the Farmer-Labor Party. The FLP, an agrarian, primarily Midwestern populist movement, had seen a skyrocketing in popularity among Middle American states, most prominently in Minnesota and Kansas, at the onset of the Depression. Until 1932, it was the only third party since the Roosevelt-era Progressives to win seats in Congress, and had sent a Minnesota representative to Congress in all but one election since 1918.

Jacob Coxey, Mayor of Massilon, Ohio and repeat FLP Presidential candidate

The Socialist Party of America, the "mainstream" American far-left political party, also made gains during this time. Capitalizing on their "foot in the door" in the form of their House seat, the SPA relentlessly pushed their agenda throughout the Depression, simultaneously supporting Roosevelt's New Deal programs while also poaching his voters. Also ascendant was the avatar of the far left and Stalin's mouthpiece in the American political scene: the Communist Party of the United States of America. Around this time, Earl Browder would emerge as the defining figure of the American Popular Front movement. Browder was originally named General-Secretary of the CPUSA's National Committee in 1932, and while he was a staunch communist, he loyally adhered to the Communist Party's line of the 1930s: a "popular front" against fascism and its champions, Mussolini and, later, Hitler.

Norman Thomas, Presbyterian minister and SPA presidential hopeful

This "Popular Front" doctrine was enacted at the Seventh Congress of the Comintern, spearheaded by Bulgarian political theorist and Comintern chairman Georgi Dimitrov and approved almost overwhelmingly by the majority of Comintern delegations. This doctrine would prove extremely influential in the coming years, especially during the civil war in Spain. For America's leftists, it meant an end to the confrontational Third Period, in which the USSR controlled large sections of the Party through the NKVD.

Georgi Dimitrov, Chairman of the Seventh Congress of the Communist International

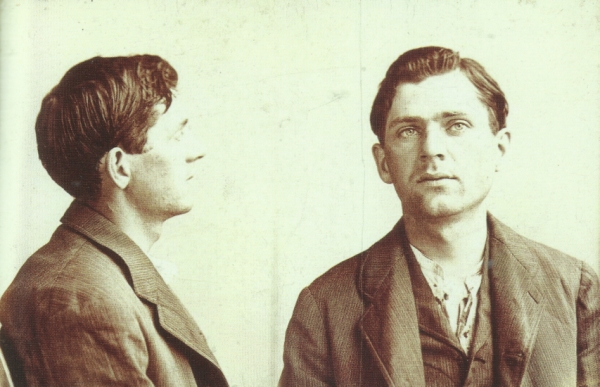

Browder addresses CPUSA members during the 1934 elections

With 1936 fast approaching, along with the fateful election that would come with it, the wheels of change were turning incessantly beneath the thin veneer of order in the United States. In the years to come, the world would be plunged into the bloodiest, most world-spanning conflict in its history--and it would be a conflict that a new America would take part in, like it or not.

Last edited:

.jpg)