The Clockwise World

There are many circumstances and unexplained phenomena that can be offered a plausible and physically possible situation. What happened 1.5 million years before the present day in this alternate timeline was not among them.

The world of the early Pleistocene was a time of interesting changes. In the early part of the infamous ice ages, the world was about to slip from a brief interglacial into a frigid glacial period, along with all the faunal upheavals that would cause. It was also a major part of human evolution, as Homo erectus was widespread across Africa and was beginning to make fire. Some humanoids had even migrated into southern Asia, with some erectus populations reaching as Far East as Java. This complicated time was about to get even more so.

The reversal of Earth's spin was not instantaneous, as such an event would cause untold devastation, but occurred over a period of just a year. After eighteen months, it seemed as if the day would stop spinning altogether. Animals and early humans experienced great shock and terror in these early times, and there was confusion among migration patterns and sleep patterns. But after six months, the earth started spinning again. But this time, the sun rose in the west and fell in the east. At first, this seemed an insignificant change in the long term, but one doesn't have to be a geological expert to review the great changes the world would go through. Within millennia, climates around the world were rendered nearly unrecognisable in some places.

With the Earth's motion going differently, the winds and ocean currents also began to alter their shapes, and reverse in many cases. Already in the midst of the Pleistocene ice ages, turmoil around the world created an even more unstable environment. The Coriolis effect went into reverse as well. Some places began to become hotter and drier, with forests being replaced by grasslands and then deserts, while in others the reverse happened. The former occurred mainly on the western shores of oceans, such as the east coast of America and east Asia, while the latter occurred on the eastern shores. In some places, due to more complicated procedures, neither extreme happened, with a few places being colder and drier or warmer and wetter. Those places furthest from the sea such as Central Asia and central Africa were the least affected, but in time they too saw other changes from the surrounding lands.

1,400,000 years BCE

With greater rainfall across Northern Africa and the Middle East, streams and dry beds filled into rivers, expanding new ones as well and filling in lake beds that would otherwise be empty saltpans. In Europe, the Gulf Stream, already weakened during glacial periods, disappeared altogether. Even during the interglacials, northern Europe's temperature dropped by more than ten degrees Celsius in a few places like Britain and Scandinavia, meaning much of Lapland remained under an ice cap even in the hot interglacials, and Southern Europe and Anatolia became 2-6 degrees cooler on average, as well as becoming much rainier, like the east coast of America had been. Fish stocks bloomed in a cooler and more oxygenated Mediterranean, now nearly freshwater, and fish eating animals thrived as well, otters, seals, dolphins, bears and many others. As a result, the following glacial period had a truly frigid Europe, though very dry due to weather patterns limiting snowfall, while more snow fell at the opposite end of northern Eurasia. Both during glacial and interglacial periods, sea levels tended to be between ten and fifteen metres lower than they would have been with normal rotation. More and larger islands, smaller seas and larger land bridges meant more islands to settle for the strange types of animals living in Mediterranean islands. Dwarf varieties of sheep, deer, hippo and even elephant started to evolve in these island habitats, as did giant varieties of smaller creatures. Even the two legged varieties started to make their way there in later times.

Of course, with a much colder and more hostile Europe came a hotter east Asia, with Kamchatka, Manchuria and southern China warming by as much 10 degrees Celsius, or even more in the latter's case, with more moderate warming in Siberia, northern China and Japan. The harsh winters that defined the land before disappeared and more moderate conditions appeared in the northeast, while the southeast developed harsher and drier summers. "Mediterranean" (as in comparable to OTL's Mediterranean) conditions could now be found as far north as Jilin and Primorsky, with even the Sakhalin peninsula looking positively English, promoting fauna from further south to move inward, especially with the conditions in China deteriorating. With the Far East being a much milder place both in glacial and interglacial times, the history of migration would change forever.

Within a mere few millennia of the event, storm patterns swapped in many places, and as this turned into tens, it stabilised on a worldwide basis. The wet and stormy Florida and dry and calm California swapped in many ways, with the lakes of western America filling instead of draining, forming wetlands and mountain forests. The east coast became hotter and drier, with even New England developing a more Mediterranean climate, while the southern part of the continent became increasingly like its counterpart on the other side of the Atlantic had been. The Caribbean coastlines as a whole became substantially hotter and drier, and one of the world's largest deserts formed, with only the Mississippi as a refuge in the centre. Various unique flora and fauna in the region were forced to adapt, migrate to the north and west, or perish. The Laurentia ice sheet was reduced due to an African current bringing warmer drier air to the region, helping some of the warmer species such as mastodons and stag moose have a place to live as southern habitat dried up. The Great Plains, enlarged eastward and hotter than before, came to resemble their African counterpart more, especially with Savannah and open woodland to the west. Mammoths and local mastodons grew larger ears and less hair in convergence to Africa's Loxodonta. Hawaii was one of the only places that became both wetter and warmer than before, and along with sea levels dropping a little, exposing more land, they became even more of a biodiversity hotspot, with its own strange flora and fauna. With a fertile west coast, a great ecological island developed in Pacifica, wetter and more seasonal than before, with lakes feeding great herds of deer, beavers, ground sloths and mastodons. With a cooler and more open north-west, and a warmer, slightly larger and longer lasting Beringia, the gateway between old world and new world was an easier one to cross…

In Australia, the desertification that slowly drained the continent reversed to something that it had been like in the past, with great herds of kangaroos, dromorniths and diprotodonts feeding off the growing greenery, fed upon by Thylacines, marsupial lions, crocodiles and monitor lizards, which all flourished. Returning bit by bit to its Miocene counterpart, Australia's anthropological status as the most dangerous continent in the world was taking on another meaning.

The desertification of south-east Asia, in contrast, cut off a particular set of erectus from the rest of their kin in India, beginning another divergence in the human line. The Yangtze River now formed another great oasis piercing through a mighty desert, like the Mississippi in America and the Nile in previous times. Indonesia and the Philippines, while significantly drier and somewhat hotter than when the planet span prograde, was still home to one of the worlds largest rainforests, even if it was more fragmented by Savannah's and open woodland than before. Life would go on as usual for the most part here.

Overall, the first hundred thousand years after the Reversal were some of the most crucial of this timeline, with fundamental habitat shifting, populations moving, extinctions here and there, and human evolution beginning to change in some ways, but not others, for the conditions leading toward greater intelligence and ingenuity were shifting elsewhere, not disappearing. Although the effects of global can definitely alter the shape of evolution and anthropology, there are also dampening effects in reality that prevent such changes from being completely unregulated, as well as the undeniable process of convergence that can create scenarios that are not so different to what would otherwise have been. As with the weather, changes do not simply spiral on infinitely, but are still subject to dampening effects in nature.

Human development was not a single linear process as was previously thought, but came in multiple waves. The first wave of early members of the genus homo coming out of Africa started about 2.1 million years ago, a while before the reversal of the earth's rotation. By the time of the Great Reversal, humans of some form or another were already present from the Caucasus to Indonesia, especially Homo erectus, and some form likely existed in Europe like Homo antecessor. Even a dwarf variety of the habilis line existed on the island of Flores. As Arabia and the Sinai peninsula became cooler and wetter, and therefore less of a barrier to cross, human migration outward and even backward became easier as a result, resulting in new genetic diversity in the region.

Of course, most migrations of humans continued to be in Africa and Southern Asia, though north Africa's greater habitability offered a great deal. With Europe considerably colder even in interglacial periods than before the Reversal, migrations into the region would be smaller and more gradual than in other regions, focussed in Iberia, Italy and the Balkans as new developments occurred in human anatomy to cope with this cold and a need to migrate into Central Asia to escape hostile conditions. During interglacial periods, populations of erectus and later humans would migrate into the Mediterranean basin, providing a temperate refuge from the cold of the north, migrating out of west Asia and the Maghreb alongside various megafauna. As cold periods became longer, however, the European landscape became ever more difficult to stay in long time, while west Asia became more prevalent. With increased human migration into Asia as a result, speciation went in this direction too. As millennia went by, differences became more noticeable.

Not affected as badly by glacial periods as Europe, east Asia still remained relatively balmy even in the worst of it, though the Nanman Desert certainly was an imposing barrier from north or south. During glacial periods of course, the wetter northeast did attract the formation of glaciers that cancelled out the reduced glaciation in a drier Europe, reaching across Yakutia and Okhost all the way to northern Manchuria. Northern China, however, especially during interglacials, proved to be an idyllic area for fauna and flora to settle from the south, and therefore for tribes of basal Homo to enter. The Yellow River, warm, fairly wet and with predictable flooding, became of great use for settlers, and would in time give rise to some of the world's first civilizations. From here, Korea and Manchuria, among other areas around the seas of Japan and Okhotsk became prime breeding grounds for hunter-gatherers to expand into. Even island hopping to Kamchatka brings some early humans there, before Homo novus had even arisen.

With interbreeding being so common between different human races, classifying exact species or subspecies wasn't and still isn't east, but the era leading to a million years before the present showed how far humans can get even in subpar conditions.

Further south in south east Asia and around the Yangtze River, cut off from other humans by a great yellow desert, the rival clans of erectus developed in relative isolation from their western counterparts. Spreading across Indonesia and into the greener parts of Indochina, especially during lower sea levels, they proliferated in small tribes, fighting off formidable creatures like mighty apes, ferocious tigers and enormous Stegodons and elephants. Here, they eventually encountered another variant of human that had arrived in the region before them. A dwarf form of habilis living on this small island, known as hobbits. Only a metre tall, and using simpler sticks, they did not have much on the tall and lanky eastern erectus, but their small size allowed them to hide effectively from the newcomers. The prey that the hobbits depended on, however was another story. Similarly in islands like Mindahou and Luzon, other erectus arrived and went down a similar path to the hobbits of insular dwarfism. More traditional erectus prospered in Indochina and Sundaland during glacials. As a result, erectus themselves became refugees in this land away from the new waves of human migration as time came on.

In the deserts of Vietnam and Nanman, they took on a more meagre existence, redeveloping the darker skin and longer strides they had in Africa, adapted to the new terrain in other ways. They also shrank in stature to accommodate for less resources and for easier loss of heat, along other adaptions for desert life. Thus came the birth of Homo cantonus, a new branch of the human tree.

Yet another branch survived the other waves of human immigration from Africa and Arabia by going in another direction. With northern China and the Far East proving inviting places to settle for Hunter gatherers, with plentiful game to hunt and small scale fire to keep themselves warm, worked their way up the coast of Okhost, beyond the comfortable borders of Manchuria. With Even Kamchatka remaining somewhat habitable during glacials, due to t way geography affects east Asia compared to Europe, a population of surviving erectus began to expand in another direction besides east. At some point between 700,000 and 800,000 years before the common era, a population of Homo erectus, believed to have numbered just in the double figures, managed the impossible and crossed the Bering Land bridge, perhaps trying to find their way back and going east instead of west, into the bounties of the Americas. This was clearly a fluke, as no other long term migrations there likely occurred until the arrival of Homo novus many millennia later, but this indeed changed the fates of the Americas and its fauna. Some would die out, and others would adapt to these newcomers, and to those after them.

As the ice ages went on, the bounties of North Africa and the Middle East, greater than they ever were in the old Pleistocene or even Pliocene, provided early humans with a great array of foods and lands to pick from, but it was not without struggle. With harsh European glacials nearly closing the straits of Gibraltar, migrations still occurred and sometimes species went extinct from pressure. The European panther was certainly one of these casualties, limited to ever smaller parts of Europe, like Greece or Anatolia. Mammoth herds grew in a much colder Europe downward into the Middle East through the Caucasus in glacial periods, displacing straight Tusked elephants in their place as they went into a cooler Arabia. With Europe harsh and hostile, Greece, Anatolia and Mesopotamia were suitable territory for the next group of human expansion into colder climates, namely heidelbergensis, which did well in these mountains and on the fringes of Europe. As interglacials went on, they would go up into the steppes and humid forests of Europe and Central Asia as well, splitting into new subspecies as they went along.

On the opposite end of the Middle East, the Arabian Savannahs and open woodlands provided an excellent refuge for a later Paranthropus species, P.epimos, by providing them with a grassy habitat with no baboons to compete with and allowing them to further the development of bosei, its ancestor. Larger and with even more pronounced jaws than its ancestors, this species grew to a similar height to the largest Homo erectus, but had a much more robust build to support a gut to consume grass and its head. Males were easily the larger, standing 1.75metres tall and weighing at least 110kg, whereas females were only 60% of the size. Instead of being an evolutionary dead-end, the greening of Africa and the Middle East provided a great path for the line of Paranthropus from their old homeland into the south Asian coasts, as would the Indian subcontinent as the Persian gulf's south coast provided land for them to transition and speciate into even more varieties going as Far East as Siam or even beyond.

Genetic admixture between the various waves of Homo emerging out of Africa created a very diverse gene pool across Eurasia, one with different branches emerging locally adapted to the terrains of the swamps and lakes of west Africa, the warm woodlands of the north, the frigidness of Europe, the varied terrains of the Middle East, the jungles of India and even the islands of south-east Asia. When Homo novus finally emerged in the open woodlands of Niger, they had a variety of other species to compete or interbreed with, taking on new traits in their new environments. By this time, many of the other human races, the Neanderthals of Europe, the Nadeli of South Africa, the Magrey of the north-west, the Denisovans of Siberia, the "Jheiniz" of north China, the Cantons of the south, and others had all entrenched themselves significantly, while lacking the sapiens' complexity of tools. The fauna of Africa and Asia, therefore while certainly having losses due to more efficient tool use, had effectively been inoculated well before H.novus arrived, giving them greater resistance. As novus spread rapidly across the various pathways of land, across the rivers and on the shores of lakes, they warred with the other species and one another, but also found common ground. The higher intuition, the desire to change the lands to their own desires, and spirituality of some form. Alliances, debates and even breeding happened between the different species and subspecies across Eurasia and Africa. The Eemian interglacial time, a time even warmer than the present, provided a particularly quick spread of humans in Eurasia, leading to the extinction of a few less adaptable megafauna and specialised human species, though the next ice age certainly delayed the further spread, at least slowing it down.

Still, by 100,000 years before the common era, the world spinning in reverse had humans of some form or another from the Naleds of the Cape Verde to the southernmost Amazonians of Cape Horn, and the impact they had on the world was already profound, wiping out specialised fauna, forcing others to change their behaviours and lifestyles, and even changing the landscapes in some ways, like clearing forests with controlled fires or changing the food chain. None, however, would have quite the impact of Homo novus, as its spread around the world became truly global.

The Study that inspired;

While partly inspired by Chris Wayan's Planetocopia series, the big up for this was a 2018 study by Mikolajewicz et al with the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, available in full here. Covering many factors, though not all of the possible variables due to limits of technology, it is nevertheless a fairly comprehensive study, if still a bit overgeneralising in places that Chris Wayan's more speculative maps were not.

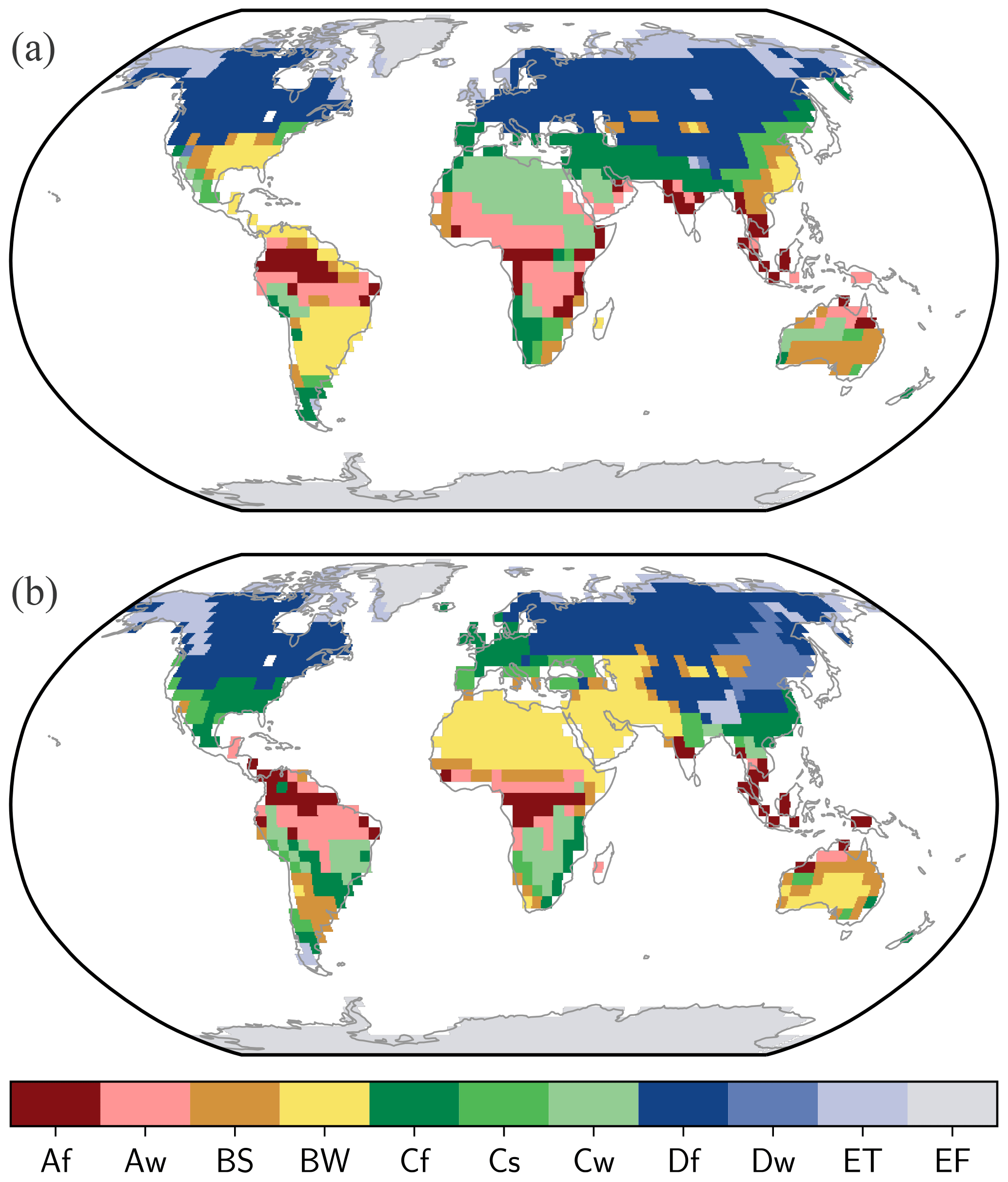

Present below are some maps comparing a backward earth relative to otl under preindustrial conditions;

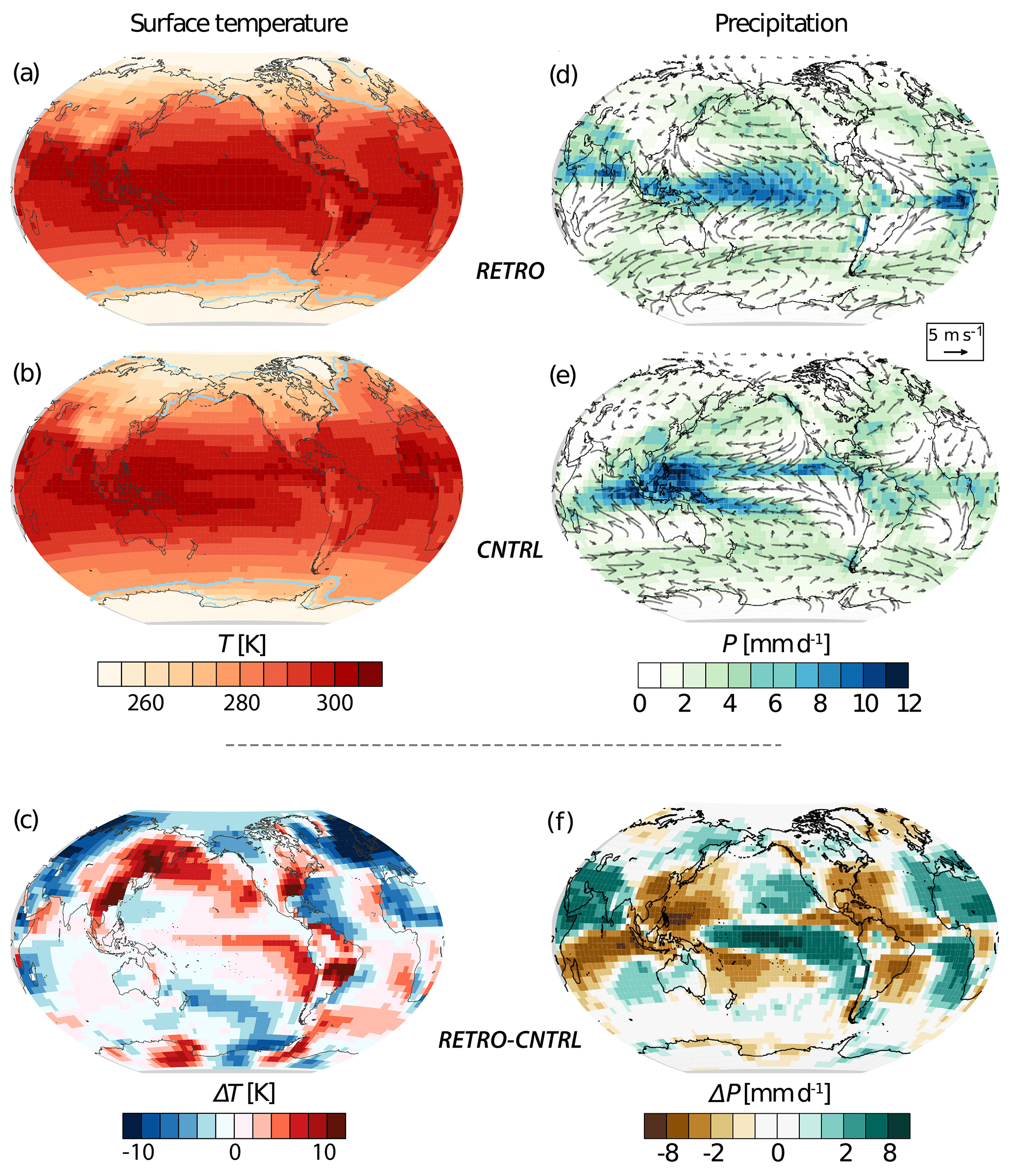

Average annual Temperature and humidity relative to otl due to reversed currents. Overall, this world likely has somewhat lower sea levels than our own due to Scandinavia being partly frozen over.

https://av.tib.eu/media/36560 (see link)

Seasonal variation in temperatures bimonthly, with otl on left and ttl on right.

Variation in temperatures throughout the day, with otl on left and ttl on right.

Denitrification in otl on the left and ttl on the right. Note a large Cyanobacteria presence off southern India's coastline.

Bimonthly precipitation with otl on left and ttl on right.

Daily precipitation with otl on left and ttl on right.

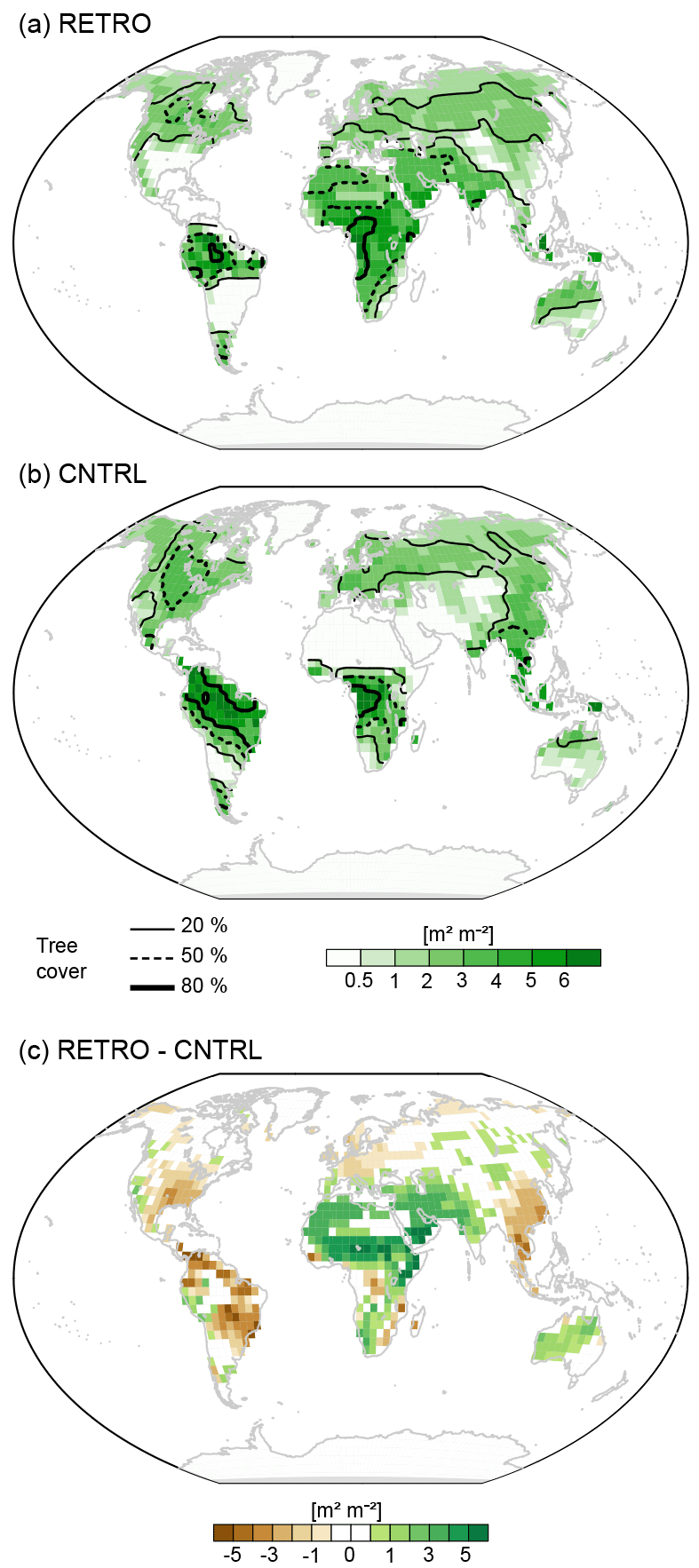

Annual leaf index with otl on left and ttl on right.

Oxygen dissolving with otl on left and ttl on right.

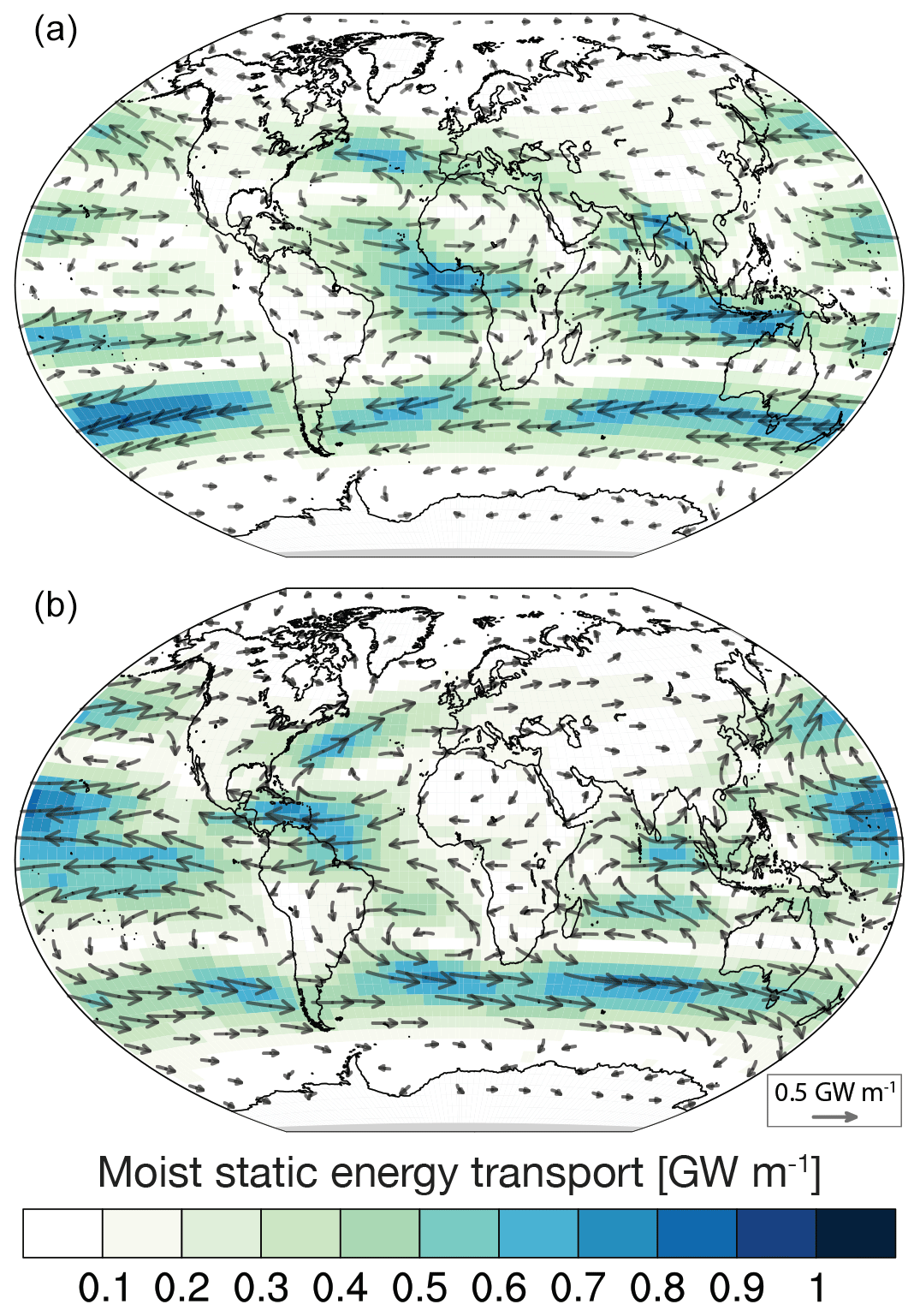

Wind strength with otl on left and ttl on right; overall, a retrograde earth has slightly stronger storms.

Polar ice. Otl on left and ttl on right. Larger ice caps likely mean lower sea levels, by about 15-20m I would reckon.

Rainfall patterns relative to otl.

Forest cover relative to otl.

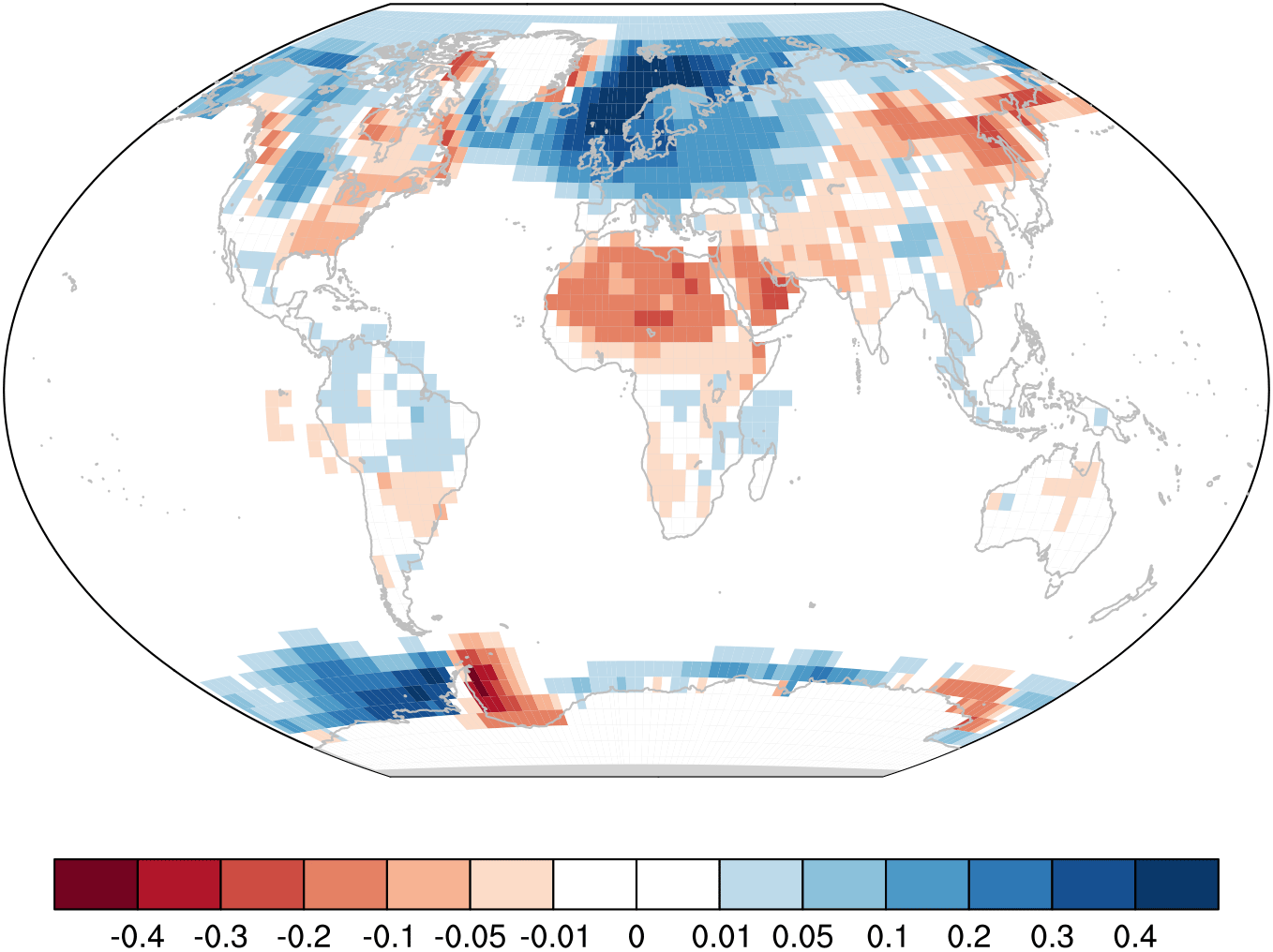

surface albedo relative to otl.

Global temperature differences. Overall, Retro is slightly cooler and wetter than our own.

Compared to otl, Retro has 10.6 million square kilometres less desert, including 5 million more for woody vegetation like woodlands and bushes and 5.6 million more for herbaceous vegetation like grasslands.

"Over the continents, the shifting isotherms mean that the eastern continental margins warm and the western lands cool in RETRO as compared to CNTRL. In the midlatitudes, these changes are skewed (reflecting the changing inclination of Humboldt's isotherms) so that the cooling in the western lands is amplified poleward, and the warming is strengthened toward the Equator. Strong warming, for instance, is evident in the southeast of Brazil (Rio de Janeiro), over the southeastern states (Atlanta) of the US, and over southeastern China (Guangzhou and the Pearl River Delta region). The strongest cooling is over the ocean, in association with winter sea ice, particularly over the North and Baltic seas, although west Africa, which is very warm in CNTRL, also cools substantially, as does British Columbia in present-day Canada. The magnitude of these changes have the effect that – from a temperature perspective – the African–European landmasses cool, and the Americas warm. Over the ocean, the cold upwelling waters evident in the present-day east equatorial Pacific largely vanish, rather than shift, in RETRO. Figure 2shows only a hint of a cold tongue stretching eastward from east Africa in the equatorial Indian Ocean."

The Changes;

General ones;

As noted in the study, eastern coasts are generally warmer and drier with milder winters at temperate latitudes and harsher summers at subtropical ones, while west coasts are the reverse. At least for the mainlands. For islands, however, eastern coast islands are often cooler and drier than our own; with notable examples including the Caribbean, Madagascar, the Mauritius, New Zealand, the Philippines and even southern Honshu, though the Falklands are a notable exception. Meanwhile western coast islands are often warmer and wetter, such as the Azores, Canaries, Verde, Aleutians, Californian Channel Islands, Galapagos and even Hawaii, though Vancouver is a notable exception.

With less desert and more greenery, this world likely has a higher carrying capacity for both biomass and human population than our own timeline. Thus despite the temporary shifts of species and ecological damage done by rapid climate change, the world ultimately may see a growth in biomass. On the flip side, should industrial civilisation still arise, this world would have (even) more to lose than our own.

Europe;

Conditions in Europe, depending on where you are at, can be pretty dramatic. Without the midatlantic bringing warm dry air upwards, the lands of Northern Europe are cooler and with much harsher winters than they were before the Reversal. Even in summer, the British isles, Scandinavia and Baltic are significantly cooler and drier, being a far cry from the home of the world's largest empire. Scandinavia and European Russia now experience Eurasia's harshest winters, comparable to our own Yakutia and Arctic Circle. These harsh taiga's and tundras make the land very hard to live in bar for herds or caribou and other such specialists. Norway has a full on glacier covering much of its coastline all year round, resulting in lower global sea levels, and during the winters, seasonal ice can reach as far south as the bay of Biscay, with the English Channel freezing over in January and thawing in April. Northern Europe as a whole is roughly comparable to our own Canada or Siberia, formidable in natural resources, but a harsh land and wilderness, home to only the hardiest of peoples.

Around the Mediterranean is a different story. While noticeably cooler in both summer and winter for the most part, [barring Portugal, Sicily and southern Spain which have similar winters but milder summers] the region is much wetter than before, along with stormier weather, making the Mediterranean almost freshwater. Now instead of hot dry summers and cool wet winters, warm wet summers and cool dry or wet winters are the norm in southern Europe as well as neighbouring Anatolia. With cooler, less salty and more oxygenated water the norm here, fishing stocks have grown quite significantly, and the Mediterranean teams with life. Species that previously thrived in western and Central Europe flew to this refuge, and during glacial periods when even this wasn't possible, they'd move to west Asia and North Africa as a refuge. A fertile land to dwell in, southern Europe in contrast to its northern counterpart still had plenty of opportunity for biomass and significant human development. With continental Europe as harsh as it is, elaborate societies north of the Alps would need to wait to a sufficient technological level to arise. Italy has a continental north and a more temperate south, leaning toward subtropical in the southern fringes, like our Korea or Japan.

Eastern Europe is even more harsh and hostile than before. Some of the coldest winters in the northern hemisphere occupy northern Russia, Karelia and Finland, and even the more moderate conditions in southern Russia and Ukraine are not what they were before the Reversal, with cooler summers and winters than before. The northern balkans have only somewhat cooler summers but much stronger winters. Only the southern balkans like Greece, Albania and Bulgaria remain relatively mild, only a bit cooler and much wetter than before, having some of the best climate in Europe for elaborate societies. The islands of the Mediterranean continued to do very well; larger with milder summers, more rain and less salty water around them, they only had to deal with storms more often, bringing new creatures and beings to the islands, becoming full of unique flora and fauna. Thus this sea was still a hub of complexity, and in the human era, trade, commerce, competition and innovation, especially with its next door neighbours.

Saharan Africa;

On the other side of the Mediterranean, another great change has taken place. Without the hot dry air coming from the Caribbean and with minerals drifting eastward from the desertifying Dixie (more in that later), the Sahara and Maghreb went through dramatic changes in weather. Cooler and much wetter than before, with monsoons coming in from Arabia, the climate of this vast area became one of the world's great hotspots.

In Africa and Australia, the environments became much greener and more fertile, to an extent not seen since the Miocene, and unlike the cyclic humid periods before, these were long term stable periods. As the Amazon shrank, the Central African rainforests and especially the surrounding subtropical forests mushroomed up. The west coast became wet and stormy like the old Florida or vietnam, and even the Maghreb came to resemble the southeastern USA in its interglacial periods, with the Atlas Mountains having iced caps that drained into rivers, creating great lakes larger than those of America in the Western Sahara. With east Africa also becoming much wetter, rainforests expanded once more into the Horn and beyond, recreating the forested conditions that humanity's ancestors came from. Had this reverse occurred at the start of the Pliocene, it would likely have prevented the separation of human and chimp ancestors, with even Sudan and Egypt having cooler Savannah's, open forests and subtropical grasslands forming. Egypt was still mainly prairie and grass rather than desert, but the open plains dwelling humans merely moved northward into the Saharan paradise away from the expanding rainforests, and then into Asia.

The Maghreb saw much milder summers and similar winters along with increased humidity, and this had very notable results. The Atlas Mountains around Morocco and Algeria were snow-capped and meltwater flowed southward to fill in rivers and lakes across inland Algeria, Mauritania and western Libya. Tunisia, due to its position, wasn't greatly wetter than before even if it did have milder summers, though it would certainly be of economic importance in the future. One of the most extreme changes in climate was in what we call Western Sahara, ironically now the most humid part of the Maghreb along with the Canaries off the coast, as well as slightly warmer in its coasts but cooler inland. The climate of this region is now comparable in both temperature and humidity to our own Florida and Bahamas respectively. Further south still, a somewhat cooler and noticeably wetter Senegal, Mauritania and Gambia lie, with thriving forests and wetlands developing along with various African fauna. Once human societies began to develop, the west African coast was a big hub of trade extending from the Mediterranean. In broad terms, the northwestern Sahara could be compared to our own southern China, southern Brazil or southeast United States in climate, though with more longitude to work with and access to the extensive Mediterranean trade networks.

The northeastern Sahara was different. While notably cooler in summer, it wasn't to the same extent as the west, and it actually had somewhat warmer winters. Instead of being year round, the increased humidity was seasonal as part of the Arabian monsoon, resulting in a strongly seasonal climate comparable roughly to our northern India. The Nile flows through from the marginally wetter Great Lakes and far wetter Horn upwards through the Sudanese savannahs and woodlands to the delta of Egypt [known as Khemros ittl], a mix of grasslands and open monsoonal woodlands. No pyramids are being built around those delta though. Coastal Egypt and Cyrenaica weren't that much wetter than before, being more grass and shrubs outside the river deltas, though more humid conditions existed further south and in Tripolitania. Lions, African tigers and some of the last Eurasian machairodonts partitioned niches and prowled for plentiful herds of fauna, including multiple varieties of elephantid and innumerable ungulates, easily able to travel through the Sahara to the south, or eastwards across Southern Asia or even the Balkans. This vast array of longitude to work with boded very well for fauna and for human development.

The far wetter southern Sudan, Chad and the northern CAR form a nearly unrecognisable environment. With the Sahel as a whole being considerably milder and wetter than before the Reversal, the cyclic lakes of the region, forming and drying with the Sahara's cycles became more permanent, as did the surrounding rivers and streams. As a result, the preciously transitional region between desert and savannah became a huge savannah itself, more than twice as large of all sub Saharan ones combined and even extending into parts of the Sahara itself. The Chadian lake became a sea as impressive as the Caspian, forming a meeting of biomes between the subtropical open woodlands and grasslands to the north, and the denser tropical savannahs to the south. Chad became a bountiful paradise of unique fish in its waters, while around it formed rich deltas and valleys full of African life all around. With such a great increase in biomass, biodiversity was bound to increase as well, as did early human numbers, as now Africa had twice as much habitable land as before. While other lands dried out and their fauna and flora struggled, those of Africa, especially the north, made good use of these new lands. Species that may otherwise have outcompeted could more easily migrate to other lands and partition niches, groups that may have gone extinct due to aridification during glacial periods experienced a resurgence as the Sahara bloomed.

The Horn also saw a dramatic change in climate. Now home to some of Africa's densest and most humid rainforests, a slightly warmer (at lest for the actual tip) Somalia and a much cooler Djibouti and Eritia were once again green and thriving, and even the latter were part of the Sahelian savannah complex. Kenya to the south also became considerably wetter and slightly cooler than before, with plenty of open and not so open woodlands replacing the grasslands, something that may have prevented the extinction of the last Deinotheres, who in our timeline became extinct there 1 million years ago, or half a million after the PoD due to their preference for humid open forests. The highlands of Ethiopia remained subtropical and mountainous, just as they had during the late Miocene and Pliocene, before the changes bought about by the Rift Valley. It is possible that had the Reversal occurred at an earlier time, humanity would never have arisen.

Sub Saharan Africa;

Apart from the Horn, the changes in sub Saharan Africa were generally more subtle, but even here, changes nonetheless occurred. The coast south of the Sahel underwent some changes; Liberia became significantly drier, leading to plains and even coastal deserts; some of the only ones in Africa now. Slightly warmer and wetter conditions exist in Dahomey, Benin and the Ivory Coast, while a slightly warmer and drier southern Nigerian coast is present. Cameroon, Gabon and the coastal Congo are greener and the same respectively, though the inland Congo has dried out into open woodlands and savannah, with the river delta being primed for human settlement. The area with the largest amount of annual precipitation in the world is located near Ascension Island in the southern tropical Atlantic, which takes on a climate more like our Palau. Further south, a wetter and greener Angola and much greener Namibia exists, with the latter and western Cape being more than enough to make up for the drying of Mozambique and the eastern Cape. Now the southwest is home to some of the only temperate habitats in Sub-Saharan Africa, a good place for settlers from within or out of Africa to call home.

A significant loser in biodiversity and habitation potential is unfortunately the islands of Madagascar and Mauritius, significantly cooler and drier than before, with much of the islands being deserts or plains. Only the southern coast is home to some smaller and cooler forests now. When the Reversal happened, a lot of Madagascar's native flora and fauna, large or small, faced the consequences. The same is true for the Dodos of Mauritius. Despite these losses, some smaller aepyornids, aardvarks, tenracs, lemurs and fossa adapted to the arid conditions and continue to make a living here even today. As human ingenuity grew, some of these desert lemurs even began to find themselves in new lands.

West Asia;

Just as with the Mediterranean, Western Asia experienced a strong degree of change in humidity and weather patterns, as Anatolia, the Fertile Cresent and Arabia became milder and much more humid. One of the most stark transformations, perhaps even more so than North Africa, was the Arabian peninsula. Turning from mostly barren desert with some oases in the west into a lusher land of subtropical woodlands in the north like northern India, mountainous forests in the west and Yemen, hot savannahs in the empty quarter akin to Africa and even south Indian-style tropical monsoon forests around Oman, Yemen and Dubai, Arabia became a biological meeting spot between Africa and India, and in future times would be a centre point for major human development. Great herds of elephants moved in of multiple species, such as Palaeoloxodon from the northwest, Loxadonta from Africa, Elephas from India and even warmer adapted species of Mammuthus from the north, partitioning niches. Desert loving camels were replaced by deer, antelope and buffaloes. This was also a great transitional territory for another branch of the hominin tree, the Paranthropus, who with a much more forested Africa and North Africa, migrated into the new Savannah's and cooler woodlands of the Middle East. With cooler, wetter conditions and an abundance of grasses, bulbs and tough vegetation to feed upon, they started to become larger and hairier, a reverse of the trend of Homo's increased hairlessness and tendency towards more intelligence. This Arabia is if anything even greener than our own India, with its wet season lasting 4 months instead of two and being more spread out. This world's Arabia would be a rich land long before the discovery of oil.

Further northeast, Persia is very humid and relatively mild, like an even more mountainous southern China, though lacking the suitable terrain for substantial rice cultivation, unlike the rest of the Middle East or North Africa. Still, the region would be prosperous and defensible, just as in our own timeline. Now ice capped and rainy, the rocky terrains of Persia and Afghanistan spawned great rivers, drifting north and filling the Caspian and Aral Seas, causing them to merge into one. In later times, these and a wetter Mediterranean would cause the two to link through rivers into a single complex of inland seas. Central Asia and Persia became a breeding ground for these Paranthropus avoiding competition from other humanoids, at least for some time. At times Arabia or Ind were weaker, the Persian residents would certainly be able to make good use of this. Persian pandas, tigers and mountain dwelling creatures did well in the highlands, while the lowlands could be used to cultivate crops by any sentient beings quite easily.

To the north, a slightly cooler and wetter Azerbaijan stood well defended from the steppes of Central Asia. While somewhat wetter than our own, the Kazakh steppes also had stronger winters and similar summers, with the clashing air creating good environment for tornadoes, while the east around lake Bhalkash [future home of a grear nomad empire] was slightly warmer and wetter than before, allowing steppe to do well there. Western Turkestan [ie the other Stans] has milder summers and is significantly wetter, just like Persia, and these mountainous subtropical forests provide good living space for beasts and men alike. Eastern Turkestan or Xinjiang is slightly warmer than our own but otherwise very similar, the distance from the ocean and surrounding mountains making it remain a desert regardless. The Tibetan Plateau, somewhat closer to the coasts was slightly warmer in summer and with milder winters was not quite as alien compared to the surrounding realm as our own, but nevertheless the plateau and its surroundings still provided a gateway between the west and the far east, being an important trade route.

Further north, western Siberia was even harsher and colder than our own, just as with European Russia. Thick taiga forests were present here, along with a cold land of mystery and intrigue to peoples from further south. While humans existed in some form in sparse forms there for nearly a million years before present, it would be only when technology and logistics reached a certain point that more substantial habitation took place.

South Asia;

Just as with the Middle East and Horn, the increased humidity began to apply to the Indian subcontinent, a not particularly dry place even before the Reversal. The deserts of the Indus and Thar valleys disappeared in favour of subtropical woodlands like those across the rear of northern India, who changed in a more subtle way; while only very slightly wetter annually than before, the humidity was spread throughout the year more evenly, making the northern half of the subcontinent along with western Burma more climatically uniform. There was also a notable increase in humidity along the western coast, where the arid plains of the Deccan Plateau found themselves replaced with expanded savannahs and even coastal rainforests. Southern India and Ceylon, now connected to the mainland due to larger ice caps, experienced some of the most radical changes in humidity, with intense year round humidity comparable to our own Philippines or Borneo taking place here. The substantially lush climate, suitable ocean currents and the Cyanobacteria deposits off the coast make this region well suited for water travel across the Indian Ocean, quite similar though not identical to the conditions of Southeast Asia in our own timeline, a region that spawned Indonesian, austronesian and Polynesian explorers and traders. Connected to the lands around them by these seas and islands, the North Indian Ocean would almost certainly be a hub of activity between Arabia and India.

Fauna wise, forest dwelling fauna like monkeys, crocodiles, pythons, lizards, apes, pigeons, water buffalo, tigers, hippos [yes, hippos historically lived in india until pretty recently] Elephas and Stegodon grew in numbers while open fauna like rhinos, lions, ostriches, antelope and even the huge asiatic Palaeoloxodon declined or moved elsewhere to more suitable lands.

The Seychelles off the coast, while a bit larger and more frequent, were more humid in the north and less so in the south than before, and offered a gateway from the subcontinent down to the rest of the Indian Ocean, such as Madagascar and beyond…

Indochina and Southeast Asia, in contrast were significantly drier as well as warmer than before. While still wet, the rainforests of Indonesia grew less dense and became split apart by savannahs in places such as the now mainland Sumatra and eastern Borneo. Even New Guinea is somewhat drier and more open than our own, though that shall be explored later. More significant differences emerged in a warmer and drier Thailand and Myanmar, where warmer and substantially less dense forests gave way to savannahs not indifferent to those of subsaharan Africa before the Reversal. This proved a good refuge for some of the warm loving lions, antelopes and straight tusked elephants preferring such habitats, especially during glacial periods where they could expand into western Indonesia. Indochina was almost unrecognisable compared to before, now having a Sahelian climate transitioning between Thailand's savannahs and the Nanman desert to the north. Some of the most extreme change occurred in the Philippines, which while only slightly different in temperature, evolved from some of the wettest land on earth into a mix of desert and grassy islands.

Above this line, southern China is also no longer like our own. Much hotter and drier, now it holds one of the world's largest deserts, with summer temperatures in the southeast regularly approaching 50C, with even the mouth of the Yangtze [Shanghai region] usually having July-August temperatures surpassing 40C. The rivers like the Yangtze, Pearl and others form refuge from the blistering heat here like veins in the body, as well as oases that rival those of our Sahara. Perhaps around one or more of these southern rivers, there will be pyramids or something like them being built.

East Asia;

As we go up the coastlines of China northward, northern China around the Yellow Sea and River is also considerably warmer and notably drier than our own, with hotter summers and milder winters and less greenery. Thus, the Yellow River and Shandong compare roughly to our Fertile Cresent, Maghreb or Anatolia in climate, albeit on a larger scale. Perhaps a similar kind of societies could be evolving here?

Further inland, outer Mongolia and the region northward around lake Baikal are somewhat wetter than our own, while having similar and slightly warmer summers respectively [Inner Mongolia is also warmer in summer] and significantly milder winters. Thus this region remains a continental climate of sorts, but more forested and with temperatures more like our European Russia or even a drier Ukraine in Inner Mongolia, with Baikal being a centre point for potential settlement, having similar temperature and humidity to otl Muscovy in addition to a Great Lake.

The Yellow Sea's northern coastline is also noticeably warmer in summers than our own, though the difference in humidity isn't as extreme as other places, with much milder winters in North Korea and Liaoning being present. Southern Korea has similar winters but warmer summers, at least on its west coast. Korea as a whole is significantly drier than our own, as is to a lesser extent Liaoning, akin to Greece, Cyprus or Sicily. Even Primorsky, while only a degree Celsius warmer than ours in July, has much milder winters making it akin to our Croatia in climate. Grapes, wheat, barley and other such crops grow well here where rice would have in another timeline. The same is true for another landmass to the east.

The islands of Japan [called Ymosh in this timeline] are interesting in how divergent they are. More uniform in temperatures than our own, Honshu is significantly drier than our own, and has a slightly cooler southern tip, as do the Rikyus to the west. Northern Honshu, however, as well as Hokkaido and Sakhalin [now a peninsula] to a greater extent, are warmer year round than our own, with milder winters and (except for Sakhalin's wetter northern tip) slightly drier climate. In fact, Sakhalin's warming is some of the most extreme in this timeline outside of the tropics, remaining above 0C all year round most years, with the southern tip of Yuhzno-Salinsk being comparable in climate and temperature to Portland; Oregon, while the wetter northern tip compares very well to our Aomori [the northern tip of Honshu]. Overall, the islands are more uniform in temperature than our own, almost like if one had rolled Italy and Britain into one. The significantly warmer Kurils to the north also allow easily island hopping to and from Hokkaido toward further northward lands.

Further north than this, the lands of Manchuria and the Russian Far East are quite notable in their changes too. Similar summers but much milder winters and somewhat more rainfall make them a much easier place to live than our own. Inner and outer Manchuria for the most part now have a temperate maritime climate, with only a wetter Amuria remaining continental, and in a milder form at that. Yakutia is no longer the coldest place in Eurasia, with the taigas here being denser and wetter than those further west, a reversal of our timeline's trends. The Okhost Sea north of outer Manchuria is warmer and significantly wetter too; Even Okhost, hundreds of miles north of the Stanavoys has temperatures and climate comparable to our own Estonia or Saint Petersburg; harsh but certainly a big improvement over before, while the lands between it and Kamchatka compare to our Bjarmaland, Finland or Karelia.

Kamchatka itself is an island of green, with streams full of salmon and bears growing fat on them, and even snakes and other creatures can dwell here without too much issue. It is the only place north of Sakhalin with a maritime climate, having a climate pretty close to that of our own Scandinavia or Cascadia, and in a prime position for exploration. It is also nearby to a number of important locations including larger and much warmer Kurils, milder, larger and slightly wetter Aleutians, and a slightly smaller Bering Strait. During glacial periods, this region would be partly frozen over due to the increased humidity in the north, with only the slightly drier southern tip being ice free, but with the southern edge of Beringia being warmer and, at least in the eastern part, a little wetter than in our timeline, there are significant implications for the migrations of flora, fauna and of course, humans.

Oceania;

With regard to the lands behind Indonesia, Australia has changed too. While not exactly "China as an island" as Chris Wayan predicted, it has definitely become more fertile overall than our own, comparable to how it was during the late Miocene and Pliocene. Connected to a somewhat drier New Guinea by lower sea levels by a thin land bridge, northern Australia is dominated by a mix of savannahs and coastal rainforests, while the western coast is an expanse of subtropical conditions not without comparison to the southeastern USA before the Reversal, with the lakes of the region remaining full of water. Even the outback is grassland instead of desert, feeding vast herds of marsupials and birds. Animal groups that were going into decline before the Reversal, such as Genyornids, Thylacines, Mekonid turtles and Quinkana underwent a revival of diversity and size not seen in millions of years. The east coast is a bit warmer and drier than our own, but not hugely so, though Palorchestid marsupials during the Pleistocene did become stranded in the southeast. A larger and less remote Tasmania wouldn't struggle with isolationism like it did in our own timeline.

New Zealand wasn't hugely different to before the Reversal, but it did noticeably cooler than before and a little drier in the north, though the south remained humid. The fauna of these islands adapted without too much issue, and the endemic fauna of the isles continued until certain sentient entities arrived.

The various smaller islands of Polynesia were of mixed changes. Larger and more frequent due to sea level changes, the islands' extreme monsoon shifted southeastward, resulting in a larger and less dense monsoonal trend. Those near Australia like the Solomon Islands and New Caledonia became significantly drier, however, while those directly east of Indonesia and the Philippines grew more humid. Even the Hawaiian islands are significantly wetter than in our timeline, as well as 2-4C warmer throughput the year, giving them tropical paradise status indeed.

North America;

While Africa, South Asia, Australia and Siberia benefited from the Reversal in biodiversity, there were other losers than Europe and China. North America experienced considerable change as a result of the Reversal on both coasts.

Labrador, Ontario and the northeast Quebec and generally became milder in winter and somewhat wetter than our own, just as with the Far East but to a lesser extent. Ironically, New England and the Mid-Atlantic now had roughly California and Oregon like climates from before the Reversal, while Nova Scotia and Newfoundland respectively have similar or slightly warmer summers and noticeably (especially in the latter's case) milder winters, making them inviting for inhabitation for fauna from south. The mid-Atlantic's hot and semi-arid climate was a big contrast to the time before and so open dwelling fauna such as horses, camelids and pronghorns did better in such territory, along with other "Mediterranean" type creatures. A variety of creatures and plants from the former New England and mid-atlantic regions began to migrate northward there as well as Quebec and even Labrador [both 2-4C warmer year round and slightly wetter], where the sea ice during winters was still present but was much briefer in interglacials. Even during the ice ages, the eastern ice cap was not quite as large as before, and the resulting Great Lakes that emerged from them were differently shaped as a result. Thus the coast of Labrador and the surrounding region could in spite of its situation sustain decent numbers of indigenous people, though not as much as the lands to the southeast for understandable reasons. The interior was significantly drier, and the midatlantic and Chicago region is a hot and very seasonal plain, with summers regularly reaching over 30C and winters 0C, comparable to our own Central Asia. These Greater Plains [as they surpass and connect with the otl Great Plains] team with great quantities of plain dwelling creature who also do well in open woodland.

Biologically, the desertification of the Carribean coastline and formation of the Dixie Desert had major consequences for local fauna and flora that previously thrived in the humid subtropical climate. They now either had to move west to a wetter and more fertile pacific, northward up into the drier east coast, adapt to new conditions or face extinction. While going through occasional cycles of greener periods (just as the Sahara did in our own timeline), the Dixie region remained mostly an ecological dead zone barring around the great river Mississippi. As a result, this concentration of greenery around a wet river basin would concentrate fauna and in time human concentrations into a relatively small space. Camels, pronghorn antelopes and even smaller and bigger eared mammoths did better in this region, as did predators such as wolves, cheetah and jackals.

The midwestern regions didn't change too much compared to our world, but the west coast is another matter. Vancouver and British Columbia as a whole had warmer summers but considerably stronger winters than before as well as drier, comparable to our own Sakhalin and Russian far east respectively. Alaska is even colder than ours, with the south being more comparable to our north or central Alaska and Yukon, aside from greater humidity. The Aleutians off the coast, however are actually warmer with milder winters than our own [about 2-4C for summer and 4-8C for winter, or 0-2C warmer in summer and 2-6C in winter than they were during the Eemian interglacial] and a little wetter too, making them more favourable for settlement by flora, fauna and humans here. Washington and Oregon are more seasonal than our own world, resembling a milder Mongolia or Manchuria respectively. Further south, California, the Great Basin and northwestern Mexico are all wetter and greener than in our timeline, with the lakes of Nevada and Utah having never dried up, while Southern California and Baja are positively Floridian in climate. If Baja is the Florida equivalent, than the warmer and wetter Channel Islands are the Bahamas equivalent. While limited by longitude by the Appalachian mountains, the west coast isn't ecologically balkanised like in our timeline, but is more synchronised with itself, thus having much greater ecological carrying capacity, as well as human capacity. To the southeast, Mexico is generally somewhat warmer and drier than ours, with central Mexico having a solid Mediterranean climate, with a relatively similar south, while the Yucatan peninsula in the southeast is much drier; coastal desert near plains and savannahs.

Central America became significantly drier than previously, with rainforests shrinking, opening into savannahs and grasslands, even some coastal deserts in places. While still a barrier of sorts, migrations between the continents did become easier for many species to another landmass.

South America;

Like the north, South America has lost a good deal of greenery. A smaller and less dense Amazon exists in northern Brazil, surrounded by savannahs, but around them is a coastal desert around Venezuela's Caribbean coast, created by a Humbolt-like cold current in the southern Caribbean, and the world's largest desert to the south, akin to our outback. Between lies plentiful savannahs, relatively unchanged from those of the Pleistocene apart from being warmer, home to many strange game with migrated from the arid south. The Parana desert is not a total dead zone, however, as Mesopotamia like conditions exist around the Rio de La Plata basin and its tributaries, not that much warmer or drier than otl. Further south, while southern Chile is much drier than our own, southern Argentina is wetter and greener, as are the Falklands off the coast.

A dramatic shift in potential in the South American continent is the Andean coast. Without the Humbolt current, it is warmer and much wetter in places than in our timeline, with coastal rainforests existing across most of Peru and what we would call the Atacama, a true irony indeed. The highlands of Peru and western Bolivia are also slightly wetter than our own; this all makes the land have a much higher carrying capacity than in our timeline, and the thin Andean rainforest is surely a treasure trove of strange life forms; various xenarthrans adapted to the cold, some of the last notungulate mammals and even some of the last gomphotheres live here. The Galapagos off the coast are much warmer and wetter than our own, more like our Mauritius.

Antarctica;

At first looking very similar, even Antarctica has some differences here and there to our own. The West Antarctic ice sheet was larger and extended our further than our own, whereas the eastern one was a little smaller. Interestingly, the "claw" of West Antarctica, while even cooler on its western side, was noticeably warmer on the claw facing side, with the islands off the coast and even the very tip of the mainland itself [a very small area mind you] remaining ice free even in winter. While this was too late to save the last of Antarctica's native fauna, the small ice free bits of land serve as a sort of extension of Patagonia here, possibly meaning exploration of the southern most continent may start earlier than in our own timeline.

A very major departure from our own world, the Retrograde Earth and its history and present shall be explored in detail.

There are many circumstances and unexplained phenomena that can be offered a plausible and physically possible situation. What happened 1.5 million years before the present day in this alternate timeline was not among them.

The world of the early Pleistocene was a time of interesting changes. In the early part of the infamous ice ages, the world was about to slip from a brief interglacial into a frigid glacial period, along with all the faunal upheavals that would cause. It was also a major part of human evolution, as Homo erectus was widespread across Africa and was beginning to make fire. Some humanoids had even migrated into southern Asia, with some erectus populations reaching as Far East as Java. This complicated time was about to get even more so.

The reversal of Earth's spin was not instantaneous, as such an event would cause untold devastation, but occurred over a period of just a year. After eighteen months, it seemed as if the day would stop spinning altogether. Animals and early humans experienced great shock and terror in these early times, and there was confusion among migration patterns and sleep patterns. But after six months, the earth started spinning again. But this time, the sun rose in the west and fell in the east. At first, this seemed an insignificant change in the long term, but one doesn't have to be a geological expert to review the great changes the world would go through. Within millennia, climates around the world were rendered nearly unrecognisable in some places.

With the Earth's motion going differently, the winds and ocean currents also began to alter their shapes, and reverse in many cases. Already in the midst of the Pleistocene ice ages, turmoil around the world created an even more unstable environment. The Coriolis effect went into reverse as well. Some places began to become hotter and drier, with forests being replaced by grasslands and then deserts, while in others the reverse happened. The former occurred mainly on the western shores of oceans, such as the east coast of America and east Asia, while the latter occurred on the eastern shores. In some places, due to more complicated procedures, neither extreme happened, with a few places being colder and drier or warmer and wetter. Those places furthest from the sea such as Central Asia and central Africa were the least affected, but in time they too saw other changes from the surrounding lands.

1,400,000 years BCE

With greater rainfall across Northern Africa and the Middle East, streams and dry beds filled into rivers, expanding new ones as well and filling in lake beds that would otherwise be empty saltpans. In Europe, the Gulf Stream, already weakened during glacial periods, disappeared altogether. Even during the interglacials, northern Europe's temperature dropped by more than ten degrees Celsius in a few places like Britain and Scandinavia, meaning much of Lapland remained under an ice cap even in the hot interglacials, and Southern Europe and Anatolia became 2-6 degrees cooler on average, as well as becoming much rainier, like the east coast of America had been. Fish stocks bloomed in a cooler and more oxygenated Mediterranean, now nearly freshwater, and fish eating animals thrived as well, otters, seals, dolphins, bears and many others. As a result, the following glacial period had a truly frigid Europe, though very dry due to weather patterns limiting snowfall, while more snow fell at the opposite end of northern Eurasia. Both during glacial and interglacial periods, sea levels tended to be between ten and fifteen metres lower than they would have been with normal rotation. More and larger islands, smaller seas and larger land bridges meant more islands to settle for the strange types of animals living in Mediterranean islands. Dwarf varieties of sheep, deer, hippo and even elephant started to evolve in these island habitats, as did giant varieties of smaller creatures. Even the two legged varieties started to make their way there in later times.

Of course, with a much colder and more hostile Europe came a hotter east Asia, with Kamchatka, Manchuria and southern China warming by as much 10 degrees Celsius, or even more in the latter's case, with more moderate warming in Siberia, northern China and Japan. The harsh winters that defined the land before disappeared and more moderate conditions appeared in the northeast, while the southeast developed harsher and drier summers. "Mediterranean" (as in comparable to OTL's Mediterranean) conditions could now be found as far north as Jilin and Primorsky, with even the Sakhalin peninsula looking positively English, promoting fauna from further south to move inward, especially with the conditions in China deteriorating. With the Far East being a much milder place both in glacial and interglacial times, the history of migration would change forever.

Within a mere few millennia of the event, storm patterns swapped in many places, and as this turned into tens, it stabilised on a worldwide basis. The wet and stormy Florida and dry and calm California swapped in many ways, with the lakes of western America filling instead of draining, forming wetlands and mountain forests. The east coast became hotter and drier, with even New England developing a more Mediterranean climate, while the southern part of the continent became increasingly like its counterpart on the other side of the Atlantic had been. The Caribbean coastlines as a whole became substantially hotter and drier, and one of the world's largest deserts formed, with only the Mississippi as a refuge in the centre. Various unique flora and fauna in the region were forced to adapt, migrate to the north and west, or perish. The Laurentia ice sheet was reduced due to an African current bringing warmer drier air to the region, helping some of the warmer species such as mastodons and stag moose have a place to live as southern habitat dried up. The Great Plains, enlarged eastward and hotter than before, came to resemble their African counterpart more, especially with Savannah and open woodland to the west. Mammoths and local mastodons grew larger ears and less hair in convergence to Africa's Loxodonta. Hawaii was one of the only places that became both wetter and warmer than before, and along with sea levels dropping a little, exposing more land, they became even more of a biodiversity hotspot, with its own strange flora and fauna. With a fertile west coast, a great ecological island developed in Pacifica, wetter and more seasonal than before, with lakes feeding great herds of deer, beavers, ground sloths and mastodons. With a cooler and more open north-west, and a warmer, slightly larger and longer lasting Beringia, the gateway between old world and new world was an easier one to cross…

In Australia, the desertification that slowly drained the continent reversed to something that it had been like in the past, with great herds of kangaroos, dromorniths and diprotodonts feeding off the growing greenery, fed upon by Thylacines, marsupial lions, crocodiles and monitor lizards, which all flourished. Returning bit by bit to its Miocene counterpart, Australia's anthropological status as the most dangerous continent in the world was taking on another meaning.

The desertification of south-east Asia, in contrast, cut off a particular set of erectus from the rest of their kin in India, beginning another divergence in the human line. The Yangtze River now formed another great oasis piercing through a mighty desert, like the Mississippi in America and the Nile in previous times. Indonesia and the Philippines, while significantly drier and somewhat hotter than when the planet span prograde, was still home to one of the worlds largest rainforests, even if it was more fragmented by Savannah's and open woodland than before. Life would go on as usual for the most part here.

Overall, the first hundred thousand years after the Reversal were some of the most crucial of this timeline, with fundamental habitat shifting, populations moving, extinctions here and there, and human evolution beginning to change in some ways, but not others, for the conditions leading toward greater intelligence and ingenuity were shifting elsewhere, not disappearing. Although the effects of global can definitely alter the shape of evolution and anthropology, there are also dampening effects in reality that prevent such changes from being completely unregulated, as well as the undeniable process of convergence that can create scenarios that are not so different to what would otherwise have been. As with the weather, changes do not simply spiral on infinitely, but are still subject to dampening effects in nature.

Human development was not a single linear process as was previously thought, but came in multiple waves. The first wave of early members of the genus homo coming out of Africa started about 2.1 million years ago, a while before the reversal of the earth's rotation. By the time of the Great Reversal, humans of some form or another were already present from the Caucasus to Indonesia, especially Homo erectus, and some form likely existed in Europe like Homo antecessor. Even a dwarf variety of the habilis line existed on the island of Flores. As Arabia and the Sinai peninsula became cooler and wetter, and therefore less of a barrier to cross, human migration outward and even backward became easier as a result, resulting in new genetic diversity in the region.

Of course, most migrations of humans continued to be in Africa and Southern Asia, though north Africa's greater habitability offered a great deal. With Europe considerably colder even in interglacial periods than before the Reversal, migrations into the region would be smaller and more gradual than in other regions, focussed in Iberia, Italy and the Balkans as new developments occurred in human anatomy to cope with this cold and a need to migrate into Central Asia to escape hostile conditions. During interglacial periods, populations of erectus and later humans would migrate into the Mediterranean basin, providing a temperate refuge from the cold of the north, migrating out of west Asia and the Maghreb alongside various megafauna. As cold periods became longer, however, the European landscape became ever more difficult to stay in long time, while west Asia became more prevalent. With increased human migration into Asia as a result, speciation went in this direction too. As millennia went by, differences became more noticeable.

Not affected as badly by glacial periods as Europe, east Asia still remained relatively balmy even in the worst of it, though the Nanman Desert certainly was an imposing barrier from north or south. During glacial periods of course, the wetter northeast did attract the formation of glaciers that cancelled out the reduced glaciation in a drier Europe, reaching across Yakutia and Okhost all the way to northern Manchuria. Northern China, however, especially during interglacials, proved to be an idyllic area for fauna and flora to settle from the south, and therefore for tribes of basal Homo to enter. The Yellow River, warm, fairly wet and with predictable flooding, became of great use for settlers, and would in time give rise to some of the world's first civilizations. From here, Korea and Manchuria, among other areas around the seas of Japan and Okhotsk became prime breeding grounds for hunter-gatherers to expand into. Even island hopping to Kamchatka brings some early humans there, before Homo novus had even arisen.

With interbreeding being so common between different human races, classifying exact species or subspecies wasn't and still isn't east, but the era leading to a million years before the present showed how far humans can get even in subpar conditions.

Further south in south east Asia and around the Yangtze River, cut off from other humans by a great yellow desert, the rival clans of erectus developed in relative isolation from their western counterparts. Spreading across Indonesia and into the greener parts of Indochina, especially during lower sea levels, they proliferated in small tribes, fighting off formidable creatures like mighty apes, ferocious tigers and enormous Stegodons and elephants. Here, they eventually encountered another variant of human that had arrived in the region before them. A dwarf form of habilis living on this small island, known as hobbits. Only a metre tall, and using simpler sticks, they did not have much on the tall and lanky eastern erectus, but their small size allowed them to hide effectively from the newcomers. The prey that the hobbits depended on, however was another story. Similarly in islands like Mindahou and Luzon, other erectus arrived and went down a similar path to the hobbits of insular dwarfism. More traditional erectus prospered in Indochina and Sundaland during glacials. As a result, erectus themselves became refugees in this land away from the new waves of human migration as time came on.

In the deserts of Vietnam and Nanman, they took on a more meagre existence, redeveloping the darker skin and longer strides they had in Africa, adapted to the new terrain in other ways. They also shrank in stature to accommodate for less resources and for easier loss of heat, along other adaptions for desert life. Thus came the birth of Homo cantonus, a new branch of the human tree.

Yet another branch survived the other waves of human immigration from Africa and Arabia by going in another direction. With northern China and the Far East proving inviting places to settle for Hunter gatherers, with plentiful game to hunt and small scale fire to keep themselves warm, worked their way up the coast of Okhost, beyond the comfortable borders of Manchuria. With Even Kamchatka remaining somewhat habitable during glacials, due to t way geography affects east Asia compared to Europe, a population of surviving erectus began to expand in another direction besides east. At some point between 700,000 and 800,000 years before the common era, a population of Homo erectus, believed to have numbered just in the double figures, managed the impossible and crossed the Bering Land bridge, perhaps trying to find their way back and going east instead of west, into the bounties of the Americas. This was clearly a fluke, as no other long term migrations there likely occurred until the arrival of Homo novus many millennia later, but this indeed changed the fates of the Americas and its fauna. Some would die out, and others would adapt to these newcomers, and to those after them.

As the ice ages went on, the bounties of North Africa and the Middle East, greater than they ever were in the old Pleistocene or even Pliocene, provided early humans with a great array of foods and lands to pick from, but it was not without struggle. With harsh European glacials nearly closing the straits of Gibraltar, migrations still occurred and sometimes species went extinct from pressure. The European panther was certainly one of these casualties, limited to ever smaller parts of Europe, like Greece or Anatolia. Mammoth herds grew in a much colder Europe downward into the Middle East through the Caucasus in glacial periods, displacing straight Tusked elephants in their place as they went into a cooler Arabia. With Europe harsh and hostile, Greece, Anatolia and Mesopotamia were suitable territory for the next group of human expansion into colder climates, namely heidelbergensis, which did well in these mountains and on the fringes of Europe. As interglacials went on, they would go up into the steppes and humid forests of Europe and Central Asia as well, splitting into new subspecies as they went along.

On the opposite end of the Middle East, the Arabian Savannahs and open woodlands provided an excellent refuge for a later Paranthropus species, P.epimos, by providing them with a grassy habitat with no baboons to compete with and allowing them to further the development of bosei, its ancestor. Larger and with even more pronounced jaws than its ancestors, this species grew to a similar height to the largest Homo erectus, but had a much more robust build to support a gut to consume grass and its head. Males were easily the larger, standing 1.75metres tall and weighing at least 110kg, whereas females were only 60% of the size. Instead of being an evolutionary dead-end, the greening of Africa and the Middle East provided a great path for the line of Paranthropus from their old homeland into the south Asian coasts, as would the Indian subcontinent as the Persian gulf's south coast provided land for them to transition and speciate into even more varieties going as Far East as Siam or even beyond.

Genetic admixture between the various waves of Homo emerging out of Africa created a very diverse gene pool across Eurasia, one with different branches emerging locally adapted to the terrains of the swamps and lakes of west Africa, the warm woodlands of the north, the frigidness of Europe, the varied terrains of the Middle East, the jungles of India and even the islands of south-east Asia. When Homo novus finally emerged in the open woodlands of Niger, they had a variety of other species to compete or interbreed with, taking on new traits in their new environments. By this time, many of the other human races, the Neanderthals of Europe, the Nadeli of South Africa, the Magrey of the north-west, the Denisovans of Siberia, the "Jheiniz" of north China, the Cantons of the south, and others had all entrenched themselves significantly, while lacking the sapiens' complexity of tools. The fauna of Africa and Asia, therefore while certainly having losses due to more efficient tool use, had effectively been inoculated well before H.novus arrived, giving them greater resistance. As novus spread rapidly across the various pathways of land, across the rivers and on the shores of lakes, they warred with the other species and one another, but also found common ground. The higher intuition, the desire to change the lands to their own desires, and spirituality of some form. Alliances, debates and even breeding happened between the different species and subspecies across Eurasia and Africa. The Eemian interglacial time, a time even warmer than the present, provided a particularly quick spread of humans in Eurasia, leading to the extinction of a few less adaptable megafauna and specialised human species, though the next ice age certainly delayed the further spread, at least slowing it down.

Still, by 100,000 years before the common era, the world spinning in reverse had humans of some form or another from the Naleds of the Cape Verde to the southernmost Amazonians of Cape Horn, and the impact they had on the world was already profound, wiping out specialised fauna, forcing others to change their behaviours and lifestyles, and even changing the landscapes in some ways, like clearing forests with controlled fires or changing the food chain. None, however, would have quite the impact of Homo novus, as its spread around the world became truly global.

The Study that inspired;

While partly inspired by Chris Wayan's Planetocopia series, the big up for this was a 2018 study by Mikolajewicz et al with the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, available in full here. Covering many factors, though not all of the possible variables due to limits of technology, it is nevertheless a fairly comprehensive study, if still a bit overgeneralising in places that Chris Wayan's more speculative maps were not.

Present below are some maps comparing a backward earth relative to otl under preindustrial conditions;

Average annual Temperature and humidity relative to otl due to reversed currents. Overall, this world likely has somewhat lower sea levels than our own due to Scandinavia being partly frozen over.

https://av.tib.eu/media/36560 (see link)

Seasonal variation in temperatures bimonthly, with otl on left and ttl on right.

Variation in temperatures throughout the day, with otl on left and ttl on right.

Denitrification in otl on the left and ttl on the right. Note a large Cyanobacteria presence off southern India's coastline.

Bimonthly precipitation with otl on left and ttl on right.

Daily precipitation with otl on left and ttl on right.

Annual leaf index with otl on left and ttl on right.

Oxygen dissolving with otl on left and ttl on right.

Wind strength with otl on left and ttl on right; overall, a retrograde earth has slightly stronger storms.

Polar ice. Otl on left and ttl on right. Larger ice caps likely mean lower sea levels, by about 15-20m I would reckon.

Rainfall patterns relative to otl.

Forest cover relative to otl.

surface albedo relative to otl.

Global temperature differences. Overall, Retro is slightly cooler and wetter than our own.

Compared to otl, Retro has 10.6 million square kilometres less desert, including 5 million more for woody vegetation like woodlands and bushes and 5.6 million more for herbaceous vegetation like grasslands.