The Murder of John Sassamon and the Trial of Tobias, Wampapaquan, and Mattashunnamo

- Location

- USA

- Pronouns

- He/Him

The Murder of John Sassamon and the Trial of Tobias, Wampapaquan, and Mattashunnamo

This upbringing made Sassamon a true believer in Eliot's message and the gospel. Eventually, he quit teaching in Natick to proselytize among unconverted tribes like the Wampanoag. Most Indians strongly rejected Sassamon's message, but Metacom saw a potential edge in his knowledge of the English and took him on as an advisor. For a while, the two were quite close as Metacom learned all he could from the man, but Sassamon's continued attempts to convert the Sachem soured the relationship. In January 1675, Sassamon fled the Wampanoag Confederacy and headed straight to Plymouth. There, he warned Governor Josiah Winslow that Metacom was planning a war. Winslow had little reason to like Metacom, but he dismissed Sassamon's warning. Winslow rarely trusted an Indian at their word.

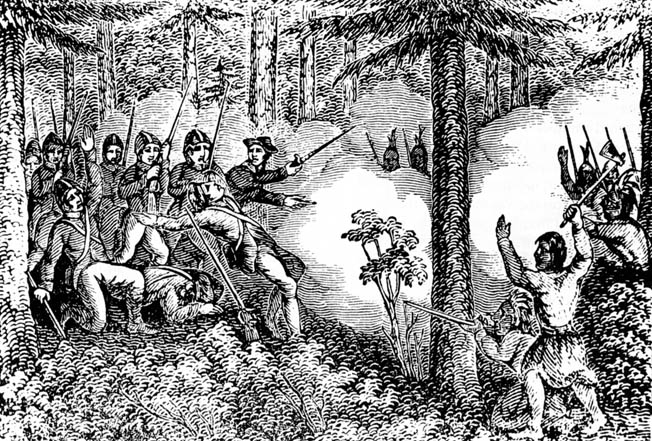

A few days passed and then Sassamon went missing. He was found at the end of January, his neck snapped, trapped under the ice of Assawompset Pond just east of Swansea. Conspiracies swirled at first, but eventually, a Praying Indian named Patuckson came forward as an eyewitness. He testified that three Wampanoag men committed the murder. The men he pointed to were important to Metacom. The most important was an advisor named Tobias, who had served as Metacom's right hand for many years. The Plymouth militia arrested him alongside his son, Wampapaquan, and another man named Mattashunnamo.

The English convened a jury of twelve colonists and six friendly Indian elders to judge the men. In June, a trial was held and all three were found guilty and executed by firing squad. Indian trust in the English court system was already low. Throughout the 1650s and 60s, the courts regularly inflicted punitive punishment on Native Americans, effectively creating a two-tier justice system in true American fashion. Common punishments for Native Americans included whippings, indentured servitude, and enslavement in Barbados. This contributed to the hatred of the English and the executions of Tobias, Wampapaquan, and Mattashunnamo have proven themselves the spark to light a powder keg. The warriors of the Wampanoag demand retribution. It is now Metacom's decision to decide not if but how this will be done.

@Dadarian, @Theaxofwar, @Greater Ale Perm

Welcome all! This post marks the start of the game. To start the first turn, I request orders from Metacom and Weetamoo about how they intend to get their revenge for Tobias, Wampapaquan, and Mattashunnamo. Once I have that, I'll write up another mini-update and likely release an order deadline for all of you. Thanks for your patience, I'm excited to get this thing underway.

Last edited: