Guderian2nd

Your (Future)Emperor

Preface

I originally wrote this essay in Korean, on a Korean online community dedicated to historical discussion. This version here is mostly a direct translation of what I originally wrote, although some corrections have been made and a few additional details added based on the feedback I received on those communities. As such, also given that I am not a native speaker of English, some of the terminology and phrasing used may be confusing or feel "off". Any feedback on that front - as well as that of grammar - is appreciated. You can read the original essay in Korean here.

To offer a bit of context on why I was spurred on to write this, essentially there was a debate primarily focused around the usage of the pike - ie. 4~6 meter long spears - as a close-combat weapon in Joseon-dynasty Korea and to a limited extent Ming China. It is a historical fact that, while in theory Joseon-dynasty Korea's armies from the 17th century and onwards were supposed to make extensive use of the pike - see this thread for another essay I wrote that covers this - in practice they did not. Both archaeological and written records of weapon depots show that the early modern Korean army's preferred close combat weapon of choice was not the pike(長槍) but ordinary polearms of <3m length and swords and shields. The main focal point there was then explaining why this was the case, in which various hypotheses were put forth, with the two main competing theories being that it had to do with the cost and variety of wood appropriate for pike making in Korea, or that it had to do with the manner in which Korean armies utilized their pikes.

As a part of this, an East-West comparison on pike tactics in the context of the early modern period on a pike and shot battlefield was brought up, more specifically on the pike in its anti-cavalry role and the spacing between pikemen in such situations, and as such I was prompted to write this article based on what I knew about the existing primary European sources of the period.

Without further ado, let's dive in.

(Original Essay Title : ) The Evolution of Spacing between Soldiers in Pike Formations throughout the 16th and 17th Centuries, focused on the Experience of the 80-Years War and the 30-Years War.

Introduction

How can we hope to examine such a broad topic? I decided that it would be the quickest to look at the primary sources, ie. the military manuals left by the veterans who actually lived and fought in the wars in question. As the primary purpose of this essay is to aide and offer information in regards to the comparative study of East-West pike tactics, I selected five sources that were readily and publicly available online, such that anyone could access and read them for themselves. I also decided to choose sources written not by those without combat experience but by actual veterans who spent at least years if not decades on the battlefields of the time. Each of the sources I present will be anywhere from ten to thirty years apart, from around the 1590s to the 1670s; select quotes from each will be commented on and analyzed, focused on the topic of "spacing between pikemen in pike formations".

Case 1 : Milicia, Discurso y Regla Militar (1586~1592)

The first source to be examined is Milicia, Discurso y Regla Militar, written by the Spaniard Captain[1] Martin de Eguiluz in 1586. While it was actually written in 1586, it was only officially published in Madrid, 1592, dedicated to Phillip II of Spain[2]. Eguiluz was a veteran of the Lowlands, having served as an officer in the Tercios of Flanders in the early period of the 80-Years War. This treatise was later republished in 1593, and 1595; the one linked above is the 1595 version. Its contents are, as can be deduced from the title, about tactics and regulations in regards to the training of the common soldiery, but more importantly the qualifications and training of the officers as well.

Page 45 of the 1595 edition (page 86 of the original 1592 edition, which is available on google books) reveals the following page:

To quote the relevant sections:

Eguiluz doesn't specify that any changes to the spacing rule are required for say, receiving a cavalry charge or for moving the formation around, which implies that he believes that this spacing suffices as a solution for most such situations. He then proceeds to explain how to calculate the frontages and depths of various formations, based on this rule, for any number of soldiers you have at your command.

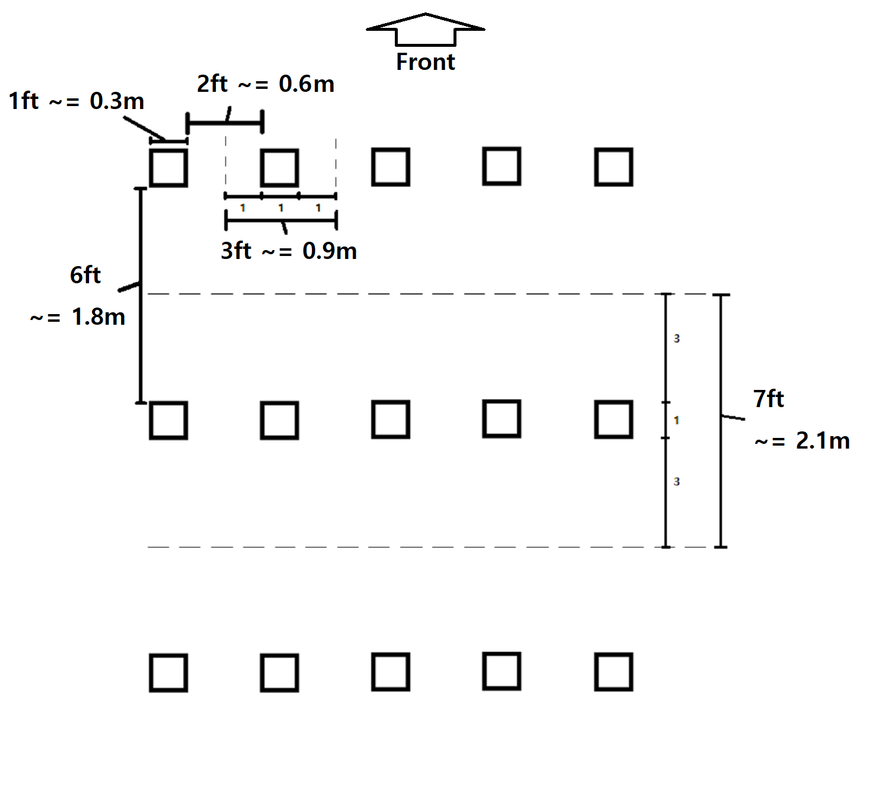

What is noticeable is that he calculates this "7 feet depth, 3 feet frontage" per man without overlapping. Therefore, we can conclude that under the "7 feet depth, 3 feet frontage" spacing as described by Eguiluz, if we assume that each soldier occupies a one feet by one feet square, means that the (right)shoulder-to-(left)shoulder distance between each column would be 2 feet, and the back-to-breast distance between each row to be 6 feet.

To visualize this, let's draw a diagram of fifteen soldiers, five men wide in frontage and three ranks deep in depth, with each soldier being represented by a square. Approximating one "feet" as 0.3 meters, the distances will be as the following:

In which the pikemen are spaced further apart depth-wise than frontage-wise.

Case 2 : The Theorike and Practike of Moderne Warres Discoursed in Dialogue Wise (1598)

The second example was published not too far apart from the treatise by Captain Eguiluz. Robert Barrett, the writer of the source linked above, also fought in the 80-Years War just like Eguiluz, although he served with not just the Spanish but also with the Italians, French, and the Dutch as well - even though of course, he himself was English[3]. This manual was the first work of literature published by Barrett after he retired, and largely covers the same topics as the work by Eguiluz. The entire early-modern text has been digitally transcribed such that it is fully searchable in the link above.

Barrett largely has the same things to say on the spacing between soldiers:

As it appears that both Barrett and Eguiluz agree on the "7 feet between ranks in depth, 3 feet between files in frontage" spacing, it would appear that said spacing was indeed the standards for the Spanish Armies of the 80-Years War, where the distance between the ranks in depth is nearly twice that of the distance between files in frontage.

How does this spacing change when we then move onto the 17th century?

Case 3 : A Discourse of Military Discipline (1634)

This treatise has a unique background behind its publication. Even though the book is written in English, it was published in Brussels, in modern day Belgium. The writer, Gerat Barry, is an Irishman, but he served in the Irish Regiments in the Army of Flanders from a young age, fighting in the Lowlands during the latter part of the 80-Years War. He held the rank of Captain by the time he wrote this book. After writing, he temporarily retired back to Ireland before becoming the supreme commander of the Irish Forces of Munster in the Irish Confederate Wars against Parlimentary England, and died of natural causes in 1646 before his revolt could be completely extinguished[4].

The book is in English despite having been published in the Lowlands because its target audience was primarily English or Irish - those Anglo-speaking soldiers who were either interested in becoming mercenaries fighting for the Spanish Crown, or were already hired arms for Spain but had only just arrived in the Lowlands and thus needed training. Like the previous manual by Barrett, this source is also 100% available online in the link above.

Being then, a treatise intended for essentially contemporary "newbies" to warfare, it is an extremely valuable source in regards to the tactics utilized by the Spanish as well as continental European armies in general at the time. Spacing between pikemen, of course, is mentioned:

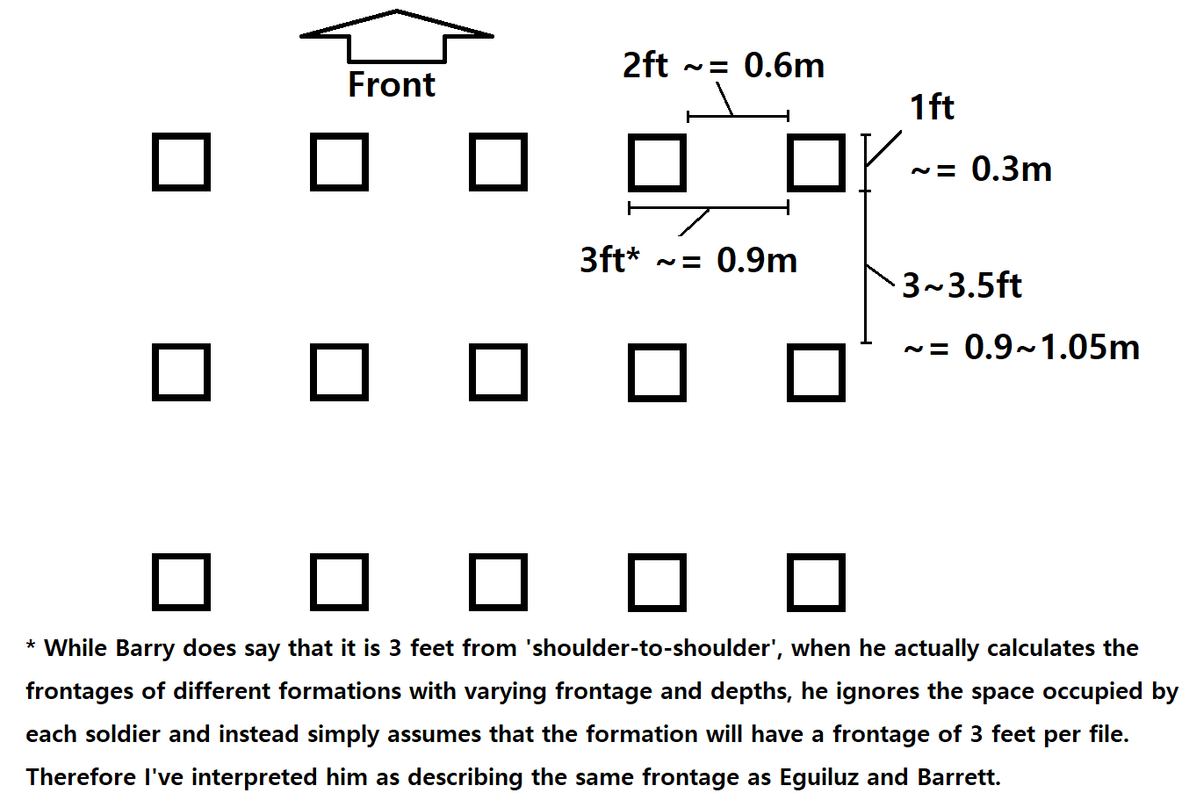

The spacing between files, ie. frontage of 3~3.5 feet per soldier as mentioned by Eguiluz or Barrett in the 1580s and 90s is seemingly kept, as well as the 7 feet spacing between rows. What is interesting, however, is that unlike Eguiluz or Barret who fought in the first phase of the 80-Years war, Barry remarks that when engaged in actual combat, the spacing between ranks (in depth) should be reduced to a mere 3~3.5 feet. To demonstrate with a diagram:

Ie. when the pikemen enter into actual combat (presumably, when approaching to contact with an enemy pike formation or when charged upon by cavalry), the spacing between rows in depth become tighter, such that the distance between each soldier in both frontage and depth become similar. We can see that broadly speaking, the formation in combat would appear to have become tighter.

Let us observe how this tendency evolves in the next source:

Case 4 : Principles of the Art Militarie (1642)

The fourth treatise is again written by an English veteran of the latter part of the 80-Years War. Henry Hexham, the writer of this treatise, served almost simultaneously with Barry. But unlike Barry, Hexham served as a mercenary for the Dutch army, not the Spanish. He reportedly was a personal friend to the famed Maurice of Naussau, Prince of Orange, having served almost entire life in the Dutch army despite being an Englishmen. Principles of the Art Militarie, which we will examine in a moment, was originally written in 1637, when Hexham held the Rank of Captain in the regiment of Lord Goring, and served as quartermaster, in the midst of the Siege of Breda. However, in 1640 he returned to England, and wrote a considerably more detailed second edition of the same treatise, publishing it in 1642, which is the edition we'll be examining. The one linked above is the second edition as well. Hexham published an English as well as a Dutch version of the same work, and as soon as he finished them he returned to the Netherlands, and continued to serve in the Dutch army until his death in 1650[5].

This particular sources goes into considerable more detail about the distances between soldiers in formation, in which we can examine how this tendency to tighten the formation in combat as described by Barry before evolved by the 1640s:

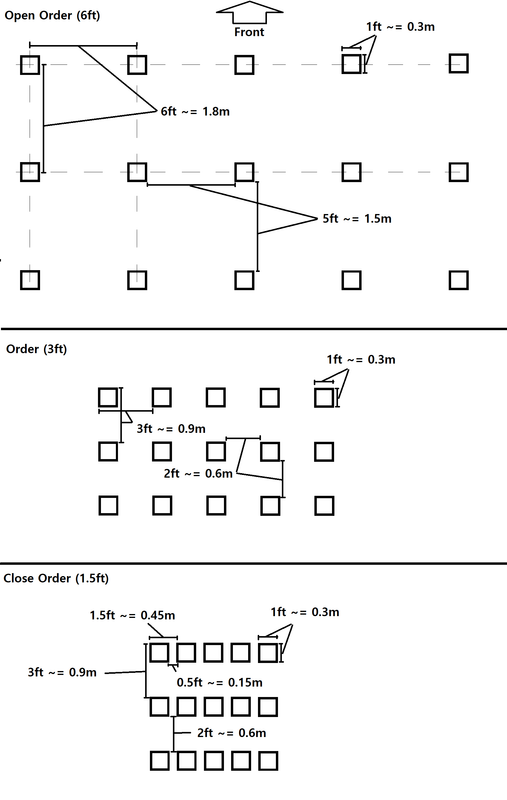

We now see that the spacing used "when occasion shall offer to fight" as described by Barry in 1634 has become a "standard" spacing of sorts, simply called "order". The spacing in which the distance between ranks is twice the distance between files - as used by Eguiluz and Barrett, and remarked upon by the former as "infallible" - has now been relegated to a formation solely used during the march.

More informatively, Hexham not only divides the various different kinds of spacing used into three but describes when these different types of spacings are used.

Open Order, in which the rank and file spacing is both 6 feet, is later described in other sections of the book as mostly being used to change the formation's overall shape or size.

Order, in which the rank and file spacing is both 3 feet, is said to be used when the formation maneuvers, or when it engages in combat, or when standing still or wheeling the pike block. As such, we can deduce that this would be the most common or "standard" spacing.

Close Order on the other hand, in which the ranks are 3 feet apart but the files are only 1.5 feet apart, is notable in that Hexham stresses in strong terms that this spacing must "never" be used except when to receive a charge, presumably a cavalry charge since you're supposed to use "Order" spacing for otherwise normal combat.

To show all three different kinds of formation spacing with a diagram:

Case 5 : Aforismi dell'Arte Bellica (1669)

The fifth and final source we'll examine are quite different from the earlier four treatises. While the writers of the previous manuals were either of common birth or that of low nobility, Aforismi dell'Arte Bellica was written by a Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, and Duke of Melfi, Raimondo Montecuccoli. Montecuccoli reportedly finished writing this treatise in 1669, but it was only published for public readers in 1704. The above google books link is a collection of Montecuccoli's works titled Opera di Raimondo Montecuccoli, published in 1852, and contains the first volume of Aforismi dell'Arte Bellica.

Having been born into a prestigious Italian noble family, Montecuccoli enlisted as a mere private soldier into an army under the command of his uncle, Count Ernesto Montecuccoli, and participated in major, era-defining battles of the 30-Years War such as Breitenfeld, Lutzen, Nordlingen, and manages to be promoted to the rank of Colonel in 1635 for his critical contribution in the retaking of Kaiserslautern. He was captured in 1639, and returns to Italy in 1642 after being released. He participated in the First War of the Castro against Pope Urban VIII, but returns to central Europe by 1643 and becomes a Lieutenant-Field Marshall[6] in the Habsburg army, gaining a seat at the Hofkriegsrat. By the end of the 30-Years War he had risen to the rank of General of the Cavalry, and was the supreme commander of the Austrian Army during the Second Northern War. He later goes on to defeat an Ottoman army nearly twice the size of his own at the Battle of Saint-Gotthard in the Fourth Austro-Turkish War, and then commanded all Imperial forces during the Franco-Dutch War, beating off the opposing army lead by French general Turenne, who was hailed at the time as being the greatest general in Europe. After retirement, he receives his HRE Princehood and the title of Duke of Melfi for his wild success, unfortunately he died due to an accident in 1680[8]. Many later military historians would go onto name Montecuccoli along with Turenne as two of the greatest generals of the mid-late 17th century in Europe.

Then what did Montecuccoli with his impeccable record say about the spacing between pikemen in formation?

We now see that there is no longer any mention of a formation like that of Eguiluz or Barrett, where the distance between ranks in depth is twice that of the spacing between files in frontage, at least when it comes to formations used by pike blocks in combat - Montecuccoli does mention a spacing like that when it comes to marching elsewhere in the book, like Hexham, but it seems like the standard spacing for Montecuccoli is a square rather than a rectangle.

Not only that, he also appears to have simplified the distances used between soldiers from the three types as described by Hexham to just two, Open Order and Close Order. In Montecuccoli's Open Order, the rank/file distance is four to five feet, with this being flexible according to need. In contrast in his Close Order, he instructs the reader to put the men close enough such that their arms do not remain free to handle. More interestingly though, despite this distinction of spacing into only two types, he later goes on elsewhere in the book to remark that on average, infantry when restricted to combat occupies an approximately 1.5 pace sized square, which would appear to be a formation spacing matching the simple "Order" spacing as given by Hexham earlier. Of course, it must be remarked that a "feet" here as used by Montecuccoli are larger than ordinary feets, as Montecuccoli notes - if a standard feet is 30cm, then one of Montecuccoli's "large geometrical feet" as he uses them would be 36cm.

This means that Montecuccoli's "1.5 paces", or 3 feet spacing for average infantry spacing is around 1.08 meters. It's a bit wider than the standard 3 feet spacing as described in earlier manuals (3 feet ~= 0.9 meters), but given that distances weren't really that standardized in the early modern era, it seems rather safe to ignore a mere 18 cm or difference and treat both as practically being the same spacing.

To show Montecuccoli's frontage and depths per man in diagram form as before:

We see that even though the formations here have gotten a lot more tighter than the formations described by Eguiluz, Barrett or Barry, the 3 feet spacing for most ordinary situations outside of being charged by cavalry is still maintained.

Analysis and Personal Thoughts

So far, we've examined how the spacing between pikemen in European pike formations changed throughout nearly a 80 year period, from the late 1580s to the late 1660s. While there can be concerns of an Anglo-centric bias, due to three of the five sources being English sources, as all of them were written by veterans who's primary background was fighting in the wars on the continent like the 80-Years War, we can probably take them to be reasonably representative of the broader continental European thought on our topic of interest.

We see that the spacing rule of "7 feet between ranks in depth, 3 feet between files in frontage" rule used by the Spanish and treated as ironclad in the 1590s become much more flexible and loose by the 1630s. In actual combat, the spacing between ranks are halved, and by the 1640s said spacing rule seems to have been transformed into a measure only used on the march. Broadly, there is a tendency for the rank/row spacing between pikes in depth to tighten as we move on from the late 16th century to the mid 17th century.

Also observed is the explicit mention of a "Close Order" used to repel cavalry in the 1640s, where we are told to make the distance between each soldier less than 1.5 feet, or 45cm. Given that the average shoulder width of adult men is around 41cm[8], this is practically telling us that the pikemen should touch shoulder-to-shoulder. An interesting fact is that we are also told by Hexham that this spacing is never to be used except to receive a charge, and the mention of the average distance between infantry soldiers engaged in combat being 1.5 paces, ie. 3 feet, by Montecuccoli. Despite the tightening of rows in pike formations mentioned earlier, the frontage of each pikemen in most combat situations is kept at this relative constant of 3 feet - around a meter, give or take 10 cm - and we rarely see this frontage decreased below this except in those situations that require repelling cavalry. This indicates to us that at least when pike blocks were trying to face enemy infantry, ie. enemy pike blocks, there likely existed a significant gap between each pikemen of a few feet which was likely required for the pike block to function effectively against infantry. Since the characteristic of the "Close Order" spacing as described by Hexham and Montecuccoli was that the arms apparently did not remain free to handle, we can go even further to posit that the purpose of this spacing between pikemen when in assuming an anti-infantry instead of anti-cavalry role was to allow the free usage and movement of the arms to actually wield the pike effectively. This is a sharp contrast to the popular image of pike blocks during the push of the pike, where pikemen stand shoulder-to-shoulder and back-to-chest even though they are facing enemy infantry, not cavalry.

We can then try to guess at the reason why the row spacing of pike formations became tighter as the 17th century progressed. The most intuitive hypothesis would be that it was simply tactically beneficial for pike formations to be tighter in spacing. This seems correct at first glance - if the spacing between each row of pikes was 6 or 7 feet, only the first three rows would be able to use their pikes against enemy infantry formations, but as Montecuccoli notes, with a row-spacing of 3 feet the density of points aimed at the enemy doubles. However, we know that this hypothesis is incomplete due to reasons already examined above - tightening the file spacing would also achieve higher point densities, but the frontages of each pikemen remain at a relative constant of a meter or so except in those cases where there is a need to repel cavalry. Therefore it is probably more accurate to posit that "the most efficient spacing against infantry is 3 feet, the most efficient spacing against cavalry is 1.5 feet or shoulder-to-shoulder".

But this then raises another question : was the spacing between pikemen even greater than the "7 feet between rows in depth, 3 feet between files in frontage" utilized by the Spanish and described by Eguiluz before the 1590s? To check this, we'd have to check upon military manuals written in the early or mid 16th century, but unfortunately doing so was beyond my personal capability and time capacity at this time.

Another question that may be raised could be about how, if the most efficient spacing to ward of cavalry was 1.5 feet between each pikemen, how did they repel cavalry when the "7 feet between rows, 3 feet between files" spacing was standard? After all, even the 3 feet by 3 feet "Order" spacing described the Hexham already appears quite loose and open to modern eyes - if the row spacing is doubled from here, it seems reasonable to question whether or not this spacing of pikemen could actually receive and repel a charge by heavy cavalry. What is certain is that Spanish Tercios and their pike blocks on the field absolutely did receive and repel plenty of cavalry charges during the 1590s or even before the 1590s. This would seem to present to us three possibilities:

1. "7 feet between rows, 3 feet between files" spacing of pikemen is more than sufficient to reliably resist cavalry charges.

2. "7 feet between rows, 3 feet between files" spacing cannot resist cavalry charges. This spacing rule was a general description by the relevant writers, rather than an ironclad rule, and actual soldiers on the field likely did contract their spacing naturally in response to enemy cavalry - likely due to psychological reasons - long before these practices were put to writing in the 1630s or 40s.

3. A combination of these two hypothesese. "7 feet between rows, 3 feet between files" probably did offer some resistance against some forms of cavalry, after all long pointy sticks are still long pointy sticks, but given that writers of military manuals eventually describe a tight, shoulder-to-shoulder formation as being most appropriate for receiving cavalry most soldiers on the field probably did contract spacing or fill it up in some way in the matter described in hypothesis 2 as above.

I personally favor hypothesis 3. I can't deny that it does seem questionable that such a loose formation could reliably deter a charge by heavily armed and armored cavalry, even if pikes are pikes, and most of the anti-cavalry effects of pike blocks come from the fact that horses in general don't like pointy sharp sticks. On the other hand, a characteristic of military manuals of this period is that they are rarely prescriptive, where some tactical genius lays out formations and tactics ex nihilo; rather, they are mostly descriptive, only describing the formations and tactics already in practical use by soldiers on the field. Ie. theory follows practice, not the other way around. As such, it is probably reasonable to assert that the 1.5 file spacing as described by Hexham or the "7 feet between rows, 3 feet between files is for marching, for combat its 3 feet for both rows and files" as described by Barry were probably already widespread practice well-known by common soldiery and officers alike, long before those writers put said practices into printed literature. Essentially, I think seeming tightening of spacing between pikemen throughout the ages as apparently shown in the military literature is illusory - armies probably dynamically adjusted spacing to be appropriate to the situation these pikemen found themselves in, as the changing situations on the battlefield demanded.

Several other factors, of course, can also be considered. It's possible that there really was a shrinking of pike blocks and their spacing from 1590 to 1660, since this is also the period in which heavy cavalry wielding sabres and lances came back into vogue; 1550~1580 was a period in which cavalry on the battlefields of Europe experimented with less shock-centered tactics like caracole or mounted arquebusiers. Perhaps the pike formations described by Eguiluz or Barrett really did maintain "7 feet between rows, 3 feet between files" all the time because there simply was no significant heavy shock cavalry threat on the field, and with its re-emergence, also came the reintroduction of true "Close Order". In essence, maybe it was the change in cavalry that caused the apparent change in row-spacing of pikemen, not any effectiveness of the pikes themselves.

Of course, in order to determine the truth, we'd need not only a deeper look into the written sources, but a geographical/archaeological study as well, relying not just on literary descriptions but the remains of "real" pike formations on real battlefields. Still, these are all interesting points to consider.

Closing Remarks

Thus we have finished our examination of the spacing between soldiers in European combat pike formations, through five select sources, from 1586~1592, 1598, 1634, 1642, and 1669 respectively, and analyzed the various facts and interesting perspectives on some aspects of how said spacing evolved and seemingly changed throughout said period.

I hope that this info dump/analysis is of interest to those interested in the topic of Early-Modern warfare and Pike-and-Shot tactics.

Special thanks to @Kyte and @Abyssien for helping with the translations for early-modern Spanish and Italian, respectively.

I originally wrote this essay in Korean, on a Korean online community dedicated to historical discussion. This version here is mostly a direct translation of what I originally wrote, although some corrections have been made and a few additional details added based on the feedback I received on those communities. As such, also given that I am not a native speaker of English, some of the terminology and phrasing used may be confusing or feel "off". Any feedback on that front - as well as that of grammar - is appreciated. You can read the original essay in Korean here.

To offer a bit of context on why I was spurred on to write this, essentially there was a debate primarily focused around the usage of the pike - ie. 4~6 meter long spears - as a close-combat weapon in Joseon-dynasty Korea and to a limited extent Ming China. It is a historical fact that, while in theory Joseon-dynasty Korea's armies from the 17th century and onwards were supposed to make extensive use of the pike - see this thread for another essay I wrote that covers this - in practice they did not. Both archaeological and written records of weapon depots show that the early modern Korean army's preferred close combat weapon of choice was not the pike(長槍) but ordinary polearms of <3m length and swords and shields. The main focal point there was then explaining why this was the case, in which various hypotheses were put forth, with the two main competing theories being that it had to do with the cost and variety of wood appropriate for pike making in Korea, or that it had to do with the manner in which Korean armies utilized their pikes.

As a part of this, an East-West comparison on pike tactics in the context of the early modern period on a pike and shot battlefield was brought up, more specifically on the pike in its anti-cavalry role and the spacing between pikemen in such situations, and as such I was prompted to write this article based on what I knew about the existing primary European sources of the period.

Without further ado, let's dive in.

(Original Essay Title : ) The Evolution of Spacing between Soldiers in Pike Formations throughout the 16th and 17th Centuries, focused on the Experience of the 80-Years War and the 30-Years War.

Introduction

How can we hope to examine such a broad topic? I decided that it would be the quickest to look at the primary sources, ie. the military manuals left by the veterans who actually lived and fought in the wars in question. As the primary purpose of this essay is to aide and offer information in regards to the comparative study of East-West pike tactics, I selected five sources that were readily and publicly available online, such that anyone could access and read them for themselves. I also decided to choose sources written not by those without combat experience but by actual veterans who spent at least years if not decades on the battlefields of the time. Each of the sources I present will be anywhere from ten to thirty years apart, from around the 1590s to the 1670s; select quotes from each will be commented on and analyzed, focused on the topic of "spacing between pikemen in pike formations".

Case 1 : Milicia, Discurso y Regla Militar (1586~1592)

The first source to be examined is Milicia, Discurso y Regla Militar, written by the Spaniard Captain[1] Martin de Eguiluz in 1586. While it was actually written in 1586, it was only officially published in Madrid, 1592, dedicated to Phillip II of Spain[2]. Eguiluz was a veteran of the Lowlands, having served as an officer in the Tercios of Flanders in the early period of the 80-Years War. This treatise was later republished in 1593, and 1595; the one linked above is the 1595 version. Its contents are, as can be deduced from the title, about tactics and regulations in regards to the training of the common soldiery, but more importantly the qualifications and training of the officers as well.

Page 45 of the 1595 edition (page 86 of the original 1592 edition, which is available on google books) reveals the following page:

To quote the relevant sections:

Eguiluz said:Esta es la medida de medio pie geometrico cuba, con que ſe deue medir todo terreno, y dos deſte que aqui ſe figura es vn pie, y ha de tener doze onças todo el, de la medida y ſuerte que aqui esta. y para la orden de pelear ocupara tres pies cada ſoldado de coſtado, poniendoſe el en medio que ocupe vno con ſu perſona, y los otros dos, vno para cada lado, y de pecho a eſpalda ha de ocupar ſiete pies, los tres dellos de vazio entre la filera que eſta delante, y el con ſu perſona vno, y los otros tres entre el y la filera que eſta detras que es la tercera: y con eſta orden ſera todo el eſquadron perfeto para pelear. que es regla infalible.

[Translation:

This is the measure of the geometric cubic half-foot, with which all terrain must be measured, and two of these pictured is a foot, and must have twelve ounces[inches] throughout. and for the order of battle must occupy three feet each soldier on the side, placing himself in the middle foot, and leaving one foot on each side, and from front to back must occupy seven feet, three feet of spacing with the row ahead, one foot for oneself and the other three feet for spacing with the row behind. With this order you will have the perfect combat squadron. It is the infallible rule.]

- de Eguiluz, Alfereze Martin. Milicia, Discurso y Regla Militar. 1st ed. Madrid: Luis Sanchel, 1592. p. 86.

Eguiluz doesn't specify that any changes to the spacing rule are required for say, receiving a cavalry charge or for moving the formation around, which implies that he believes that this spacing suffices as a solution for most such situations. He then proceeds to explain how to calculate the frontages and depths of various formations, based on this rule, for any number of soldiers you have at your command.

What is noticeable is that he calculates this "7 feet depth, 3 feet frontage" per man without overlapping. Therefore, we can conclude that under the "7 feet depth, 3 feet frontage" spacing as described by Eguiluz, if we assume that each soldier occupies a one feet by one feet square, means that the (right)shoulder-to-(left)shoulder distance between each column would be 2 feet, and the back-to-breast distance between each row to be 6 feet.

To visualize this, let's draw a diagram of fifteen soldiers, five men wide in frontage and three ranks deep in depth, with each soldier being represented by a square. Approximating one "feet" as 0.3 meters, the distances will be as the following:

In which the pikemen are spaced further apart depth-wise than frontage-wise.

Case 2 : The Theorike and Practike of Moderne Warres Discoursed in Dialogue Wise (1598)

The second example was published not too far apart from the treatise by Captain Eguiluz. Robert Barrett, the writer of the source linked above, also fought in the 80-Years War just like Eguiluz, although he served with not just the Spanish but also with the Italians, French, and the Dutch as well - even though of course, he himself was English[3]. This manual was the first work of literature published by Barrett after he retired, and largely covers the same topics as the work by Eguiluz. The entire early-modern text has been digitally transcribed such that it is fully searchable in the link above.

Barrett largely has the same things to say on the spacing between soldiers:

Barrett said:The table drawne aforesayd for the proportion of equality, that is, that the battell do containe so many men in breadth as in length, shall serue also to shew the order which is to bee obserued in the battels that are to be be made of more men in front then in flanke, that is, in proportion of inequality, as hereafter I will shew you, giuing you to vnderstand that all the figures shall haue their scala de∣uided into pases,* and euery geometricall pase into 5 foote, of the which measure of feete I haue here vnder set downe the fourth part, which is three inches, for that euery foote is deuided into 12 inches, to the end you may conceiue what quantity of ground euery battell of pikes would require, allowing for euery mans station set in aray to fight, 3 foote in front, that is, from pouldron to pouldron, and 7 foote in flanke, that is 3 foote before, and 3 foote behind, for the vse of his weapon, and one foote for his owne station.

- Barrett, Robert. The Theorike and Practike of Moderne Warres Discoursed in Dialogue Wise. London: John Crosley, 1598; Ann Arbor: Text Creation Partnership, 2011. The theorike and practike of moderne vvarres discoursed in dialogue vvise. VVherein is declared the neglect of martiall discipline: the inconuenience thereof: the imperfections of manie training captaines: a redresse by due regard had: the fittest weapons for our moderne vvarre: the vse of the same: the parts of a perfect souldier in generall and in particular: the officers in degrees, with their seuerall duties: the imbattailing of men in formes now most in vse: with figures and tables to the same: with sundrie other martiall points. VVritten by Robert Barret. Comprehended in sixe bookes.. p.51-52.

As it appears that both Barrett and Eguiluz agree on the "7 feet between ranks in depth, 3 feet between files in frontage" spacing, it would appear that said spacing was indeed the standards for the Spanish Armies of the 80-Years War, where the distance between the ranks in depth is nearly twice that of the distance between files in frontage.

How does this spacing change when we then move onto the 17th century?

Case 3 : A Discourse of Military Discipline (1634)

This treatise has a unique background behind its publication. Even though the book is written in English, it was published in Brussels, in modern day Belgium. The writer, Gerat Barry, is an Irishman, but he served in the Irish Regiments in the Army of Flanders from a young age, fighting in the Lowlands during the latter part of the 80-Years War. He held the rank of Captain by the time he wrote this book. After writing, he temporarily retired back to Ireland before becoming the supreme commander of the Irish Forces of Munster in the Irish Confederate Wars against Parlimentary England, and died of natural causes in 1646 before his revolt could be completely extinguished[4].

The book is in English despite having been published in the Lowlands because its target audience was primarily English or Irish - those Anglo-speaking soldiers who were either interested in becoming mercenaries fighting for the Spanish Crown, or were already hired arms for Spain but had only just arrived in the Lowlands and thus needed training. Like the previous manual by Barrett, this source is also 100% available online in the link above.

Being then, a treatise intended for essentially contemporary "newbies" to warfare, it is an extremely valuable source in regards to the tactics utilized by the Spanish as well as continental European armies in general at the time. Spacing between pikemen, of course, is mentioned:

Barry said:It is to be understoode that the rule whiche is observed in setinge in order or array Souldieres, is that from the shoulder of the one to the shoulder of the other, is required 3. foote or at the moste three and haulf, and from ranke to ranke 7. foote, meaninge from the breaste of the one to the backe of the other. But when occasion shall offer to fighte 3. foote or 3 ½. is i noghe from ranke to ranke meaninge frō the breste of the owne to the backe of the other, and one for his one statiō, soe that he ocupies before and behinde, and for his person 7. foote.

- Barry, Gerat. A Discourse of Military Discipline. Brussels: Widow of Jhon Mommart, 1634; Ann Arbor: Text Creation Partnership, 2011. A discourse of military discipline devided into three boockes, declaringe the partes and sufficiencie ordained in a private souldier, and in each officer; servinge in the infantery, till the election and office of the captaine generall; and the laste booke treatinge of fire-wourckes of rare executiones by sea and lande, as alsoe of firtifasions [sic]. Composed by Captaine Gerat Barry Irish.. p. 68-69.

The spacing between files, ie. frontage of 3~3.5 feet per soldier as mentioned by Eguiluz or Barrett in the 1580s and 90s is seemingly kept, as well as the 7 feet spacing between rows. What is interesting, however, is that unlike Eguiluz or Barret who fought in the first phase of the 80-Years war, Barry remarks that when engaged in actual combat, the spacing between ranks (in depth) should be reduced to a mere 3~3.5 feet. To demonstrate with a diagram:

Ie. when the pikemen enter into actual combat (presumably, when approaching to contact with an enemy pike formation or when charged upon by cavalry), the spacing between rows in depth become tighter, such that the distance between each soldier in both frontage and depth become similar. We can see that broadly speaking, the formation in combat would appear to have become tighter.

Let us observe how this tendency evolves in the next source:

Case 4 : Principles of the Art Militarie (1642)

The fourth treatise is again written by an English veteran of the latter part of the 80-Years War. Henry Hexham, the writer of this treatise, served almost simultaneously with Barry. But unlike Barry, Hexham served as a mercenary for the Dutch army, not the Spanish. He reportedly was a personal friend to the famed Maurice of Naussau, Prince of Orange, having served almost entire life in the Dutch army despite being an Englishmen. Principles of the Art Militarie, which we will examine in a moment, was originally written in 1637, when Hexham held the Rank of Captain in the regiment of Lord Goring, and served as quartermaster, in the midst of the Siege of Breda. However, in 1640 he returned to England, and wrote a considerably more detailed second edition of the same treatise, publishing it in 1642, which is the edition we'll be examining. The one linked above is the second edition as well. Hexham published an English as well as a Dutch version of the same work, and as soon as he finished them he returned to the Netherlands, and continued to serve in the Dutch army until his death in 1650[5].

This particular sources goes into considerable more detail about the distances between soldiers in formation, in which we can examine how this tendency to tighten the formation in combat as described by Barry before evolved by the 1640s:

Hexham said:Thirdly, to vnderstand well the three distances, namely, Open order, order & close order.

The Definition

Open order then, or the first distance is, when the souldiers both in Ranke, and File, stand sixe foot removed one from an other, as the scale, and this figure following shewe.

Observations

Because the measure of these distances cannot be taken so exactly by the eye, we take the di∣stance of sixe foote between File and File, by commanding the souldiers, as they stand, to stretch foorth their armes, and stand so remoued one from an other that their hands may meete.

And for the Rankes, we make account we take the same distance of sixe foot, when the butt end of the pikes doe almost reach their heeles, that march before them.

The second distance, or your Order is, when your men stand three foot remoued one from an other both in Ranke and File, and this order is to be vsed when they are embattailled, or march in the face of an Enne∣my, or when they come to stand, or when you will wheele, as this next figure represents.

Observations

VVee take the second order, or distance betweene File and File, by bidding the souldiers sett their armes a Kenbowe, and put themselves so closse; that their elbowes maye meete. And wee reckon wee take the same distance betweene the Rankes, when they come vp almust to the swords point.

Note, that when you march throw any countrie, you most observe three foote onely from File to File, and sixe from Ranke to Ranke.

The third distance, or your close order is commanded by this word Close which is, when there is one foote and a halfe from File to File, and three from Ranke to Ranke, as this Figure demonstrates.

Observe that though this figure stands but at a foote and a halfe distance: yet this is for the pikes onely, and must never be used, but when you will stand firme to receive the charge of an Ennemy. The mus∣kettiers must never be closer, then the second distance of three foote in square, because they are to have a free vse of their Armes.

- Hexham, Henry. Principles of the Art Militarie. Vol. 1. Delf: Henry Hexham, 1642; Ann Arbor: Text Creation Partnership, 2011. The first part of the principles of the art military practiced in the warres of the United Netherlands, vnder the command of His Highnesse the Prince of Orange our Captaine Generall, for as much as concernes the duties of a souldier, and the officers of a companie of foote, as also of a troupe of horse, and the excerising of them through their severall motions : represented by figure, the word of commaund and demonstration / composed by Captaine Henry Hexham, Quartermaster to the Honourable Colonell Goring.. p. 18-19.

We now see that the spacing used "when occasion shall offer to fight" as described by Barry in 1634 has become a "standard" spacing of sorts, simply called "order". The spacing in which the distance between ranks is twice the distance between files - as used by Eguiluz and Barrett, and remarked upon by the former as "infallible" - has now been relegated to a formation solely used during the march.

More informatively, Hexham not only divides the various different kinds of spacing used into three but describes when these different types of spacings are used.

Open Order, in which the rank and file spacing is both 6 feet, is later described in other sections of the book as mostly being used to change the formation's overall shape or size.

Order, in which the rank and file spacing is both 3 feet, is said to be used when the formation maneuvers, or when it engages in combat, or when standing still or wheeling the pike block. As such, we can deduce that this would be the most common or "standard" spacing.

Close Order on the other hand, in which the ranks are 3 feet apart but the files are only 1.5 feet apart, is notable in that Hexham stresses in strong terms that this spacing must "never" be used except when to receive a charge, presumably a cavalry charge since you're supposed to use "Order" spacing for otherwise normal combat.

To show all three different kinds of formation spacing with a diagram:

Case 5 : Aforismi dell'Arte Bellica (1669)

The fifth and final source we'll examine are quite different from the earlier four treatises. While the writers of the previous manuals were either of common birth or that of low nobility, Aforismi dell'Arte Bellica was written by a Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, and Duke of Melfi, Raimondo Montecuccoli. Montecuccoli reportedly finished writing this treatise in 1669, but it was only published for public readers in 1704. The above google books link is a collection of Montecuccoli's works titled Opera di Raimondo Montecuccoli, published in 1852, and contains the first volume of Aforismi dell'Arte Bellica.

Having been born into a prestigious Italian noble family, Montecuccoli enlisted as a mere private soldier into an army under the command of his uncle, Count Ernesto Montecuccoli, and participated in major, era-defining battles of the 30-Years War such as Breitenfeld, Lutzen, Nordlingen, and manages to be promoted to the rank of Colonel in 1635 for his critical contribution in the retaking of Kaiserslautern. He was captured in 1639, and returns to Italy in 1642 after being released. He participated in the First War of the Castro against Pope Urban VIII, but returns to central Europe by 1643 and becomes a Lieutenant-Field Marshall[6] in the Habsburg army, gaining a seat at the Hofkriegsrat. By the end of the 30-Years War he had risen to the rank of General of the Cavalry, and was the supreme commander of the Austrian Army during the Second Northern War. He later goes on to defeat an Ottoman army nearly twice the size of his own at the Battle of Saint-Gotthard in the Fourth Austro-Turkish War, and then commanded all Imperial forces during the Franco-Dutch War, beating off the opposing army lead by French general Turenne, who was hailed at the time as being the greatest general in Europe. After retirement, he receives his HRE Princehood and the title of Duke of Melfi for his wild success, unfortunately he died due to an accident in 1680[8]. Many later military historians would go onto name Montecuccoli along with Turenne as two of the greatest generals of the mid-late 17th century in Europe.

Then what did Montecuccoli with his impeccable record say about the spacing between pikemen in formation?

Montecuccoli said:XXII. Vi ha due sorta d'intervalli e di distanze fra i soldati, cioè a file aperte e file serrate. A file più o meno aperte, contansi quattro o cinque piedi d'intervallo, cioè quello spazio che è fra una persona e l'altra, fra un cavallo e l'altro, di fronte o di fondo. Egli varia conforme al disegno che si ha o di far l'esercizio, o di non impedirsi l'un l'altro con le armi, o di far la contromarcia, o di dar via e passaggio a qualche truppa o pezzo d'artiglieria che fosse stato un tempo dietro in appiatto, come in agguato, o dare luogo tra fila e fila di picche alle file de'moschettieri le quali sparano e si ritirano fino a tanto che si venga vicino alle prese, o di aprir maggior voto ed uscite ai tiri del cannone inimico cui si sta esposto.

A file serrate, quanto più i soldati sono insieme rin stretti, salvo che le braccia rimangano libere a maneggiarsi, tanto meglio è; e dee altresi la cavalleria, salvo che i cavalli non si calpestino, nè si facciano soprapposte, strettissimamente serrarsi. Tra fanti e cavalli, trá uno squadrone e l'altro, tra i moschettieri e i picchieri, deonsi lasciare strade di fronte e di fondo, più o meno larghe, conforme al bisogno.

Si ragguaglia un passo andante a due piedi grandi geometrici, e per conseguenza cinque passi a dieci piedi che fanno dieci verghe di Rilandia: onde trecento passi andanti vagliono sessanta verghe, tiro ordinario del moschetto. Notisi che la verga di Rilandia contiene propriamente piedi dodici; ma per la comodità del calcolo viene in dieci divisa, onde questi piedi sono più lunghi degli altri, restando la verga la stessa.

XXIII. Si lunghe sono le picche, che quelle della sesta fila possono con le lor punte giungere alla prima, e quando un baltaglione fosse composto di cento file di picche, non può adoperarsene se non quattro o cinque, perchè, poniamo esser quella diciotto piedi lunga, tre di essi circa sono occupati dalle mani, onde alla prima picca restano liberi 15 piedi. La seconda fila, oltre a quello che ella v'impiega, ne consuma tre nello spazio tra l'una fila e l'altra infrapposto, di modo che egli non resta di picca se non dodici piedi. Alla terza fila ne restano nove, alla quarta sei, alla quinta ne restano tre.

[Translation:

XXII. There are two kinds of intervals and distances between soldiers, that is, in open lines and in closed lines. With open lines, count four or five feet of interval, that is, the space between one person and another, between one horse and another, from the extremities. This varies according to the battle plan, when one has to maneuver, or not to hinder each other with weapons, or to reverse the direction, or to give away and pass some troop or piece of artillery had once been right behind, as if in an ambush, or to give place between the rows and rows of pikes to the rows of musketeers who shoot and retreat until they come close to grappling, or to leave the greatest opening and exit to the shots from the enemy cannon to which you are exposed.

In tight rows, how much more the soldiers are together, except that the arms remain free to handle, the better; and the cavalry is likewise required, except that the horses trample, nor overlap each other, tightly tightened. Between infantry and cavalry, between one squadron and the other, between musketeers and pikemen, it is necessary to leave roads from the extremities, more or less wide, according to need.

(1) * A pace is recorded at two large geometric feet, and consequently five paces at ten feet that make ten rods of Rilandia: hence three hundred paces are worth sixty rods, which is ordinary musket shooting. Notice that the rod of Rilandia properly contains twelve feet; but for the convenience of the calculation it is divided into ten, so these feet are longer than the others, the rod remaining the same.

XXIII. So long are the pikes, that those of the sixth row can reach the first with their points, and when a battalion was made up of a hundred rows of pikes, it cannot use but four or five, because, let's say that [the pikes are] eighteen feet long, about three of them are occupied by the hands, so that the first pike remains 15 feet free. The second row, in addition to the one employed by you, consumes three in the space between one row and the other interposed, so that it does not remain pike if not twelve feet. In the third row there are nine, in the fourth six, in the fifth there are three. ]

- Montecuccoli, Raimondo. Opera Di Raimondo Montecuccoli . Edited by Giuseppe Grassi and Ugo Foscolo. 1. Vol. 1. Torino: Tipografia Economica, 1852. p. 100-101.

Montecuccoli said:Si calcola che un fantaccino quando egli è ben ristretto per combattere occupi tanto di fianco quanto di i tergo un passo e mezzo, e un cavaliere due di fianco e tre da tergo;

[Translation:

It is estimated that a foot soldier, when he is well restricted to combat, occupies one pace and a half from the side as well as from the rear, and a rider two from the side and three from the rear; ]

- Montecuccoli, Raimondo. Opera Di Raimondo Montecuccoli . Edited by Giuseppe Grassi and Ugo Foscolo. 1. Vol. 1. Torino: Tipografia Economica, 1852. p. 233.

We now see that there is no longer any mention of a formation like that of Eguiluz or Barrett, where the distance between ranks in depth is twice that of the spacing between files in frontage, at least when it comes to formations used by pike blocks in combat - Montecuccoli does mention a spacing like that when it comes to marching elsewhere in the book, like Hexham, but it seems like the standard spacing for Montecuccoli is a square rather than a rectangle.

Not only that, he also appears to have simplified the distances used between soldiers from the three types as described by Hexham to just two, Open Order and Close Order. In Montecuccoli's Open Order, the rank/file distance is four to five feet, with this being flexible according to need. In contrast in his Close Order, he instructs the reader to put the men close enough such that their arms do not remain free to handle. More interestingly though, despite this distinction of spacing into only two types, he later goes on elsewhere in the book to remark that on average, infantry when restricted to combat occupies an approximately 1.5 pace sized square, which would appear to be a formation spacing matching the simple "Order" spacing as given by Hexham earlier. Of course, it must be remarked that a "feet" here as used by Montecuccoli are larger than ordinary feets, as Montecuccoli notes - if a standard feet is 30cm, then one of Montecuccoli's "large geometrical feet" as he uses them would be 36cm.

This means that Montecuccoli's "1.5 paces", or 3 feet spacing for average infantry spacing is around 1.08 meters. It's a bit wider than the standard 3 feet spacing as described in earlier manuals (3 feet ~= 0.9 meters), but given that distances weren't really that standardized in the early modern era, it seems rather safe to ignore a mere 18 cm or difference and treat both as practically being the same spacing.

To show Montecuccoli's frontage and depths per man in diagram form as before:

We see that even though the formations here have gotten a lot more tighter than the formations described by Eguiluz, Barrett or Barry, the 3 feet spacing for most ordinary situations outside of being charged by cavalry is still maintained.

Analysis and Personal Thoughts

So far, we've examined how the spacing between pikemen in European pike formations changed throughout nearly a 80 year period, from the late 1580s to the late 1660s. While there can be concerns of an Anglo-centric bias, due to three of the five sources being English sources, as all of them were written by veterans who's primary background was fighting in the wars on the continent like the 80-Years War, we can probably take them to be reasonably representative of the broader continental European thought on our topic of interest.

We see that the spacing rule of "7 feet between ranks in depth, 3 feet between files in frontage" rule used by the Spanish and treated as ironclad in the 1590s become much more flexible and loose by the 1630s. In actual combat, the spacing between ranks are halved, and by the 1640s said spacing rule seems to have been transformed into a measure only used on the march. Broadly, there is a tendency for the rank/row spacing between pikes in depth to tighten as we move on from the late 16th century to the mid 17th century.

Also observed is the explicit mention of a "Close Order" used to repel cavalry in the 1640s, where we are told to make the distance between each soldier less than 1.5 feet, or 45cm. Given that the average shoulder width of adult men is around 41cm[8], this is practically telling us that the pikemen should touch shoulder-to-shoulder. An interesting fact is that we are also told by Hexham that this spacing is never to be used except to receive a charge, and the mention of the average distance between infantry soldiers engaged in combat being 1.5 paces, ie. 3 feet, by Montecuccoli. Despite the tightening of rows in pike formations mentioned earlier, the frontage of each pikemen in most combat situations is kept at this relative constant of 3 feet - around a meter, give or take 10 cm - and we rarely see this frontage decreased below this except in those situations that require repelling cavalry. This indicates to us that at least when pike blocks were trying to face enemy infantry, ie. enemy pike blocks, there likely existed a significant gap between each pikemen of a few feet which was likely required for the pike block to function effectively against infantry. Since the characteristic of the "Close Order" spacing as described by Hexham and Montecuccoli was that the arms apparently did not remain free to handle, we can go even further to posit that the purpose of this spacing between pikemen when in assuming an anti-infantry instead of anti-cavalry role was to allow the free usage and movement of the arms to actually wield the pike effectively. This is a sharp contrast to the popular image of pike blocks during the push of the pike, where pikemen stand shoulder-to-shoulder and back-to-chest even though they are facing enemy infantry, not cavalry.

We can then try to guess at the reason why the row spacing of pike formations became tighter as the 17th century progressed. The most intuitive hypothesis would be that it was simply tactically beneficial for pike formations to be tighter in spacing. This seems correct at first glance - if the spacing between each row of pikes was 6 or 7 feet, only the first three rows would be able to use their pikes against enemy infantry formations, but as Montecuccoli notes, with a row-spacing of 3 feet the density of points aimed at the enemy doubles. However, we know that this hypothesis is incomplete due to reasons already examined above - tightening the file spacing would also achieve higher point densities, but the frontages of each pikemen remain at a relative constant of a meter or so except in those cases where there is a need to repel cavalry. Therefore it is probably more accurate to posit that "the most efficient spacing against infantry is 3 feet, the most efficient spacing against cavalry is 1.5 feet or shoulder-to-shoulder".

But this then raises another question : was the spacing between pikemen even greater than the "7 feet between rows in depth, 3 feet between files in frontage" utilized by the Spanish and described by Eguiluz before the 1590s? To check this, we'd have to check upon military manuals written in the early or mid 16th century, but unfortunately doing so was beyond my personal capability and time capacity at this time.

Another question that may be raised could be about how, if the most efficient spacing to ward of cavalry was 1.5 feet between each pikemen, how did they repel cavalry when the "7 feet between rows, 3 feet between files" spacing was standard? After all, even the 3 feet by 3 feet "Order" spacing described the Hexham already appears quite loose and open to modern eyes - if the row spacing is doubled from here, it seems reasonable to question whether or not this spacing of pikemen could actually receive and repel a charge by heavy cavalry. What is certain is that Spanish Tercios and their pike blocks on the field absolutely did receive and repel plenty of cavalry charges during the 1590s or even before the 1590s. This would seem to present to us three possibilities:

1. "7 feet between rows, 3 feet between files" spacing of pikemen is more than sufficient to reliably resist cavalry charges.

2. "7 feet between rows, 3 feet between files" spacing cannot resist cavalry charges. This spacing rule was a general description by the relevant writers, rather than an ironclad rule, and actual soldiers on the field likely did contract their spacing naturally in response to enemy cavalry - likely due to psychological reasons - long before these practices were put to writing in the 1630s or 40s.

3. A combination of these two hypothesese. "7 feet between rows, 3 feet between files" probably did offer some resistance against some forms of cavalry, after all long pointy sticks are still long pointy sticks, but given that writers of military manuals eventually describe a tight, shoulder-to-shoulder formation as being most appropriate for receiving cavalry most soldiers on the field probably did contract spacing or fill it up in some way in the matter described in hypothesis 2 as above.

I personally favor hypothesis 3. I can't deny that it does seem questionable that such a loose formation could reliably deter a charge by heavily armed and armored cavalry, even if pikes are pikes, and most of the anti-cavalry effects of pike blocks come from the fact that horses in general don't like pointy sharp sticks. On the other hand, a characteristic of military manuals of this period is that they are rarely prescriptive, where some tactical genius lays out formations and tactics ex nihilo; rather, they are mostly descriptive, only describing the formations and tactics already in practical use by soldiers on the field. Ie. theory follows practice, not the other way around. As such, it is probably reasonable to assert that the 1.5 file spacing as described by Hexham or the "7 feet between rows, 3 feet between files is for marching, for combat its 3 feet for both rows and files" as described by Barry were probably already widespread practice well-known by common soldiery and officers alike, long before those writers put said practices into printed literature. Essentially, I think seeming tightening of spacing between pikemen throughout the ages as apparently shown in the military literature is illusory - armies probably dynamically adjusted spacing to be appropriate to the situation these pikemen found themselves in, as the changing situations on the battlefield demanded.

Several other factors, of course, can also be considered. It's possible that there really was a shrinking of pike blocks and their spacing from 1590 to 1660, since this is also the period in which heavy cavalry wielding sabres and lances came back into vogue; 1550~1580 was a period in which cavalry on the battlefields of Europe experimented with less shock-centered tactics like caracole or mounted arquebusiers. Perhaps the pike formations described by Eguiluz or Barrett really did maintain "7 feet between rows, 3 feet between files" all the time because there simply was no significant heavy shock cavalry threat on the field, and with its re-emergence, also came the reintroduction of true "Close Order". In essence, maybe it was the change in cavalry that caused the apparent change in row-spacing of pikemen, not any effectiveness of the pikes themselves.

Of course, in order to determine the truth, we'd need not only a deeper look into the written sources, but a geographical/archaeological study as well, relying not just on literary descriptions but the remains of "real" pike formations on real battlefields. Still, these are all interesting points to consider.

Closing Remarks

Thus we have finished our examination of the spacing between soldiers in European combat pike formations, through five select sources, from 1586~1592, 1598, 1634, 1642, and 1669 respectively, and analyzed the various facts and interesting perspectives on some aspects of how said spacing evolved and seemingly changed throughout said period.

I hope that this info dump/analysis is of interest to those interested in the topic of Early-Modern warfare and Pike-and-Shot tactics.

Special thanks to @Kyte and @Abyssien for helping with the translations for early-modern Spanish and Italian, respectively.

Footnotes

[1] Capitan.

[2] de Leon, Fernando Gonzalez. "'Doctors of the Military Discipline': Technical Expertise and the Paradigm of the Spanish Soldier in the Early Modern Period." The Sixteenth Century Journal 27, no. 1 (1996): 61–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/2544269. p. 73.

[3] Stephen, Leslie. "Barret, Robert." Article. In Dictionary of National Biography 3, 3:279–80. New York: Macmillan, 1885.

[4] Matthew, Henry Colin Gray, and Brian Harrison, eds. "Barry, Gerat." Article. In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 4, 4:130–31. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2004.

[5] Pollard, Albert Frederick. "Henry, Hexham." Article. In Dictionary of National Biography, Supplement 2, edited by Sidney Lee, 2:418–19. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1901.

[6] Feldmarschall-Lieutenant

[7] Chisholm, Hugh, eds. "Montecuccoli, Raimondo, Count Of." Article. In Encyclopædia Britannica 18, 11th ed., 18:279–80. Cambridge University Press, 1911.

[8] Watson, Kathryn. "Average Shoulder Width and How to Measure Yours." Healthline. Healthline Media, October 27, 2018. Average Shoulder Width and How to Measure Yours.

[1] Capitan.

[2] de Leon, Fernando Gonzalez. "'Doctors of the Military Discipline': Technical Expertise and the Paradigm of the Spanish Soldier in the Early Modern Period." The Sixteenth Century Journal 27, no. 1 (1996): 61–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/2544269. p. 73.

[3] Stephen, Leslie. "Barret, Robert." Article. In Dictionary of National Biography 3, 3:279–80. New York: Macmillan, 1885.

[4] Matthew, Henry Colin Gray, and Brian Harrison, eds. "Barry, Gerat." Article. In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 4, 4:130–31. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2004.

[5] Pollard, Albert Frederick. "Henry, Hexham." Article. In Dictionary of National Biography, Supplement 2, edited by Sidney Lee, 2:418–19. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1901.

[6] Feldmarschall-Lieutenant

[7] Chisholm, Hugh, eds. "Montecuccoli, Raimondo, Count Of." Article. In Encyclopædia Britannica 18, 11th ed., 18:279–80. Cambridge University Press, 1911.

[8] Watson, Kathryn. "Average Shoulder Width and How to Measure Yours." Healthline. Healthline Media, October 27, 2018. Average Shoulder Width and How to Measure Yours.

Barrett, Robert. The Theorike and Practike of Moderne Warres Discoursed in Dialogue Wise. London: John Crosley, 1598; Ann Arbor: Text Creation Partnership, 2011. The theorike and practike of moderne vvarres discoursed in dialogue vvise. VVherein is declared the neglect of martiall discipline: the inconuenience thereof: the imperfections of manie training captaines: a redresse by due regard had: the fittest weapons for our moderne vvarre: the vse of the same: the parts of a perfect souldier in generall and in particular: the officers in degrees, with their seuerall duties: the imbattailing of men in formes now most in vse: with figures and tables to the same: with sundrie other martiall points. VVritten by Robert Barret. Comprehended in sixe bookes..

Barry, Gerat. A Discourse of Military Discipline. Brussels: Widow of Jhon Mommart, 1634; Ann Arbor: Text Creation Partnership, 2011. A discourse of military discipline devided into three boockes, declaringe the partes and sufficiencie ordained in a private souldier, and in each officer; servinge in the infantery, till the election and office of the captaine generall; and the laste booke treatinge of fire-wourckes of rare executiones by sea and lande, as alsoe of firtifasions [sic]. Composed by Captaine Gerat Barry Irish..

Chisholm, Hugh, eds. "Montecuccoli, Raimondo, Count Of." Article. In Encyclopædia Britannica 18, 11th ed., 18:279–80. Cambridge University Press, 1911.

de Eguiluz, Alfereze Martin. Milicia, Discurso y Regla Militar. 1st ed. Madrid: Luis Sanchel, 1592.

Hexham, Henry. Principles of the Art Militarie. Vol. 1. Delf: Henry Hexham, 1642; Ann Arbor: Text Creation Partnership, 2011. The first part of the principles of the art military practiced in the warres of the United Netherlands, vnder the command of His Highnesse the Prince of Orange our Captaine Generall, for as much as concernes the duties of a souldier, and the officers of a companie of foote, as also of a troupe of horse, and the excerising of them through their severall motions : represented by figure, the word of commaund and demonstration / composed by Captaine Henry Hexham, Quartermaster to the Honourable Colonell Goring..

de Leon, Fernando Gonzalez. "'Doctors of the Military Discipline': Technical Expertise and the Paradigm of the Spanish Soldier in the Early Modern Period." The Sixteenth Century Journal 27, no. 1 (1996): 61–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/2544269.

Matthew, Henry Colin Gray, and Brian Harrison, eds. "Barry, Gerat." Article. In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 4, 4:130–31. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2004.

Montecuccoli, Raimondo. Opera Di Raimondo Montecuccoli . Edited by Giuseppe Grassi and Ugo Foscolo. 1. Vol. 1. Torino: TIpografia Economica, 1852.

Pollard, Albert Frederick. "Henry, Hexham." Article. In Dictionary of National Biography, Supplement 2, edited by Sidney Lee, 2:418–19. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1901.

Stephen, Leslie. "Barret, Robert." Article. In Dictionary of National Biography 3, 3:279–80. New York: Macmillan, 1885.

Watson, Kathryn. "Average Shoulder Width and How to Measure Yours." Healthline. Healthline Media, October 27, 2018. Average Shoulder Width and How to Measure Yours.

Barry, Gerat. A Discourse of Military Discipline. Brussels: Widow of Jhon Mommart, 1634; Ann Arbor: Text Creation Partnership, 2011. A discourse of military discipline devided into three boockes, declaringe the partes and sufficiencie ordained in a private souldier, and in each officer; servinge in the infantery, till the election and office of the captaine generall; and the laste booke treatinge of fire-wourckes of rare executiones by sea and lande, as alsoe of firtifasions [sic]. Composed by Captaine Gerat Barry Irish..

Chisholm, Hugh, eds. "Montecuccoli, Raimondo, Count Of." Article. In Encyclopædia Britannica 18, 11th ed., 18:279–80. Cambridge University Press, 1911.

de Eguiluz, Alfereze Martin. Milicia, Discurso y Regla Militar. 1st ed. Madrid: Luis Sanchel, 1592.

Hexham, Henry. Principles of the Art Militarie. Vol. 1. Delf: Henry Hexham, 1642; Ann Arbor: Text Creation Partnership, 2011. The first part of the principles of the art military practiced in the warres of the United Netherlands, vnder the command of His Highnesse the Prince of Orange our Captaine Generall, for as much as concernes the duties of a souldier, and the officers of a companie of foote, as also of a troupe of horse, and the excerising of them through their severall motions : represented by figure, the word of commaund and demonstration / composed by Captaine Henry Hexham, Quartermaster to the Honourable Colonell Goring..

de Leon, Fernando Gonzalez. "'Doctors of the Military Discipline': Technical Expertise and the Paradigm of the Spanish Soldier in the Early Modern Period." The Sixteenth Century Journal 27, no. 1 (1996): 61–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/2544269.

Matthew, Henry Colin Gray, and Brian Harrison, eds. "Barry, Gerat." Article. In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 4, 4:130–31. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2004.

Montecuccoli, Raimondo. Opera Di Raimondo Montecuccoli . Edited by Giuseppe Grassi and Ugo Foscolo. 1. Vol. 1. Torino: TIpografia Economica, 1852.

Pollard, Albert Frederick. "Henry, Hexham." Article. In Dictionary of National Biography, Supplement 2, edited by Sidney Lee, 2:418–19. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1901.

Stephen, Leslie. "Barret, Robert." Article. In Dictionary of National Biography 3, 3:279–80. New York: Macmillan, 1885.

Watson, Kathryn. "Average Shoulder Width and How to Measure Yours." Healthline. Healthline Media, October 27, 2018. Average Shoulder Width and How to Measure Yours.

Last edited: