- Location

- Gladstone, OR

Tenra Bansho Zero: An Essay Series by Shyft

An Introduction to the Introduction

Hi! I'm Shyft, and I have too many projects. What's one more?

Of my many loves and hobbies, game design and development is ever so near and dear to my heart. I enjoy reading systems and digesting their contents, doing post mortems of their design, art direction and mechanical implementations. I make no claim to having truly deep or insightful thoughts, but I have thoughts all the same and I want to share them.

With that in mind, I felt like now is the time to at least start something I've been putting off for years, since I really heard about it across the internet- looking in on a niche-of-a-niche publication by the name of Tenra Bansho Zero. I had heard of it in passing of course, in game-finder threads and incidental discussions, but compared to the juggernauts of Dungeons and Dragons, the Storyteller stable of game lines and so on, there wasn't a lot of signal for this particular entry.

A quick look at this forum's history showed me that the last time it had been brought up for discussion was back in 2014, the edition I am drawing from for this analysis and essay series was published back in 2000- but had been translated for western audiences back in 2012-13. This document, translated or not, is in essence over two decades old.

On that note, Tenra Bansho Zero: Heaven and Earth Edition is still for-sale on DrivethruRPG. I won't be linking it per se, but since it is still 'on sale', I won't be grabbing interior excerpts of its text or artwork even if I desperately want to. I don't know what is or isn't fair-use of those assets in this context. With that in mind, I may break and do a textual description of what I'm looking at, and cite the page numbers so that those with their own copies can examine them.

That also brings to mind that, this is going to be posted on as a forum thread, and in that regard I invite discussion! In a very real sense, the 'essays' posted to the thread are a rough draft, unreviewed and unfiltered.

With that in mind, let's dive in!

Why Heaven and Earth?

So, I have for a decade now been thoroughly enmeshed in eastern mythology, culture and genre conceits just by dint of liking games and anime. To say nothing of my public and vociferous engagement with White Wolf/Onxy Path's Exalted in its varied editions.

So the opportunity to look at a game-about-japanese-things, but written by citizens of Japan was a really neat sounding idea. The introductory note by the translation team really underlined this- in that they had to actually greatly expand the book with references and cultural cues that the original edition simply assumed the readers would know.

Its like how in western media, it's abundantly easy to rely on our cultural coding and tropes of knights, cowboys and green-garbed GIs. We see those tropes and codes invoked and reinforced so much that we don't need to explain them except to outsiders, and it is much the same here with TBZ.

As a related point, it is going to be an interesting experience seeing all the shared ancestry between the videogames, TTRPG settings and comics that I have digested in my life, taken not so much in a different direction, but rooted in a different quality of soil.

Judging a Book by its Cover

So with a quick, somewhat inconclusive search, I determined that there aren't really any obvious examples or captures of the Japanese publication of the game, or the original 2000 edition, so I don't have something to compare it to except my own experiential history.

The cover is, in a very real sense the thing that can and will hook you on something. The tone-setter, the taste-maker. The cover is either going to be relevant to the topic at hand, understated as to simply be, or try to draw the reader in with some kind of captivating image.

Why yes, I am alluding to the prevalence of sexy women on book covers, even when those women aren't in the book or are not as sexy in the book.

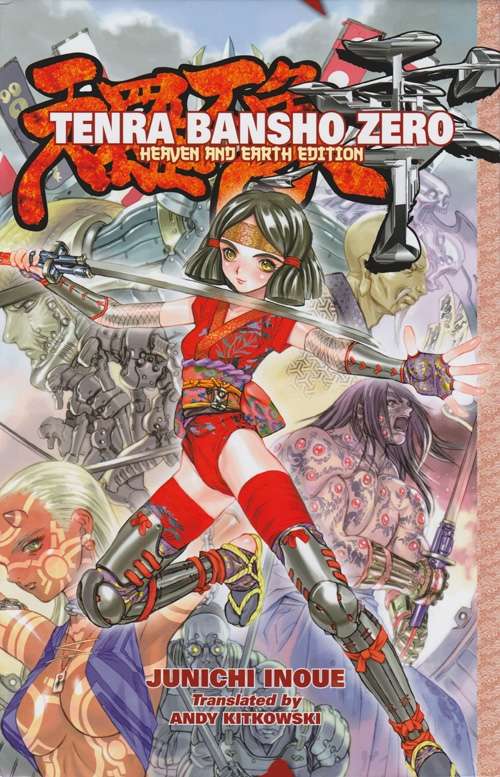

More seriously, the edition of the book I am looking at has a bright, vibrant and unmistakably anime-influenced cover. Since the cover is so readily apparent, I feel no issue in posting an embed to it under spoilers, but I will say it is mildly Not-Safe-For-Work.

Different cultures have different mores and beliefs when it comes to content- I was about to say inappropriate content, but I think that's actually a bad choice of words. The other factor is that there are different audiences for content, and TBZ is at its core, targeted at 15+ year olds, likely males, and thus borrows heavily from the Shonen and Seinin stables of fanservice.

The cover is colorful, engaging and bright. And something of important note- the lead writer or 'director' of the game, credited as Jun'ichi Inoue, is also one of the primary artists of both the cover, and interior color and monochrome illustrations.

This immediately tells me that this is a passion project, as much as anything else. TTRPGs as a broad generality, attract passionate, creative people who want to come together to make something cool. The realities and vagaries of publication, making a profit or anything like that- while not far from their minds, are often romanticized into less of a trial than one might expect.

I don't have a real picture of the publishing strategy or challenges the original developers overcame. (FEAR Co, standing for Far East Amusement Research). I can only make the broadest comparisons to how TTRPGs in the west have been developed, so I encourage anyone with insight into the industry to share their thoughts.

I don't know if the translated edition switched the family/given name order, so I'll try to be consistent when referring to development staff. Inoue in this case, being one of the primary art/visual leads and game director gives me an already strong impression of coherency, or at least hopes for such! I am still reading the book and I haven't even gotten past the credits!

Anyway- The cover, as a splash image is indicative of a lot of the stuff you can see in the game. From the logo to the buff samurai covered in eye-crystals, robot skeleton warriors, vaguely Jin-Roh -esque bottom-frame soldiers, lovely oni-woman in bottom left and wizened man in top right. It's already a melting pot of cool and sick drawing from a host of different sources, cultural conceits and media touchstones.

Of equal importance, is that nearly everything in this cover is obviously Japanese. Or at least drawing from the greater eastern cultural pool. From the design of the cyborg's woven hat, to the skull-profile faces of the robot warriors looking more like the masks samurai wear. Oni or ogres in japanese myth were of course often much more rough-looking, but cute oni is such a stable now, popularized by characters such as Urusai Yastua's Lum, that at a glance 'character with horns' immediately registers as Oni.

There is also very specific coding about those horns- compared to say the classic western demon or devil horns that are often much more explicitly based on an animal, say goat or ram. That is to say, I don't know what animal oni horns are meant to evoke if any, since they tend to be short and straight or in TBZ's case, essentially flesh-textured as opposed to bone.

I Understood That Reference!

What follows after the cover are eight lavish pages of full color comic illustrations. I took a moment to check, and the text and reading direction of the book was flipped for western audiences. I haven't actually gotten to the translator's note yet on page 33. We're still on page 3.

We've got giant robots, interlaced with an opening text crawl that wouldn't be out of place in the opening narration of a post-apocalyptic anime or film.

"Wars upon Wars, lasting for over 400 years. Even now, there is no hope, no end in sight."

"Demons and Asura rampage in a world of unending bloodshed. This land is called…"

Tenra.

In a very real sense, I am reminded of Wh40k's now immortal tagline- for in the grim dark future there is only war. (Nevermind that line is the very end of a much longer far more relevant bit of prose that people snip out for the meme).

There are robots, there are abandoned hulks of ancient war machines, we get the idea that a single Samurai somehow defeated an entire mechanized infantry unit in the span of 1-2 panels.

More pages give us brief introductions to the world of Tenra and its tone- it is dark and deadly, with hope and growth juxtaposed against sunbleached bone and a man musing on the futility of war. Of a lovely kunoichi swearing vengeance on someone who claimed they had no choice- who in turn reveals that they have pit themselves against their own daughter as they draw ofuda for a throwdown.

Interwoven in this comic section is opening credits, not unlike that of a film or anime.

A blast of fire show us a mech, vaguely skeletal in design- made more obvious in the following panel as we see it obviously modeled after a skull with four red glowing eye-lenses and sculpted teeth.

I'll take this image down if need be, but it is an excerpt of a page and is important:

Yes, yes that is exactly what you think it is- that is so on-the-nose Evangelion.

The final pages of this comic introduction is a two-page spread of a ruined battlefield, a sword sticking out of the wastes over a beautiful sunset with backlit cloud-cover- and the iconic bold aggressive brushstroke kanji we come to know as a stylistic flourish in manga and anime. I can only assume it is the title of the game, but I don't actually know!

Characterful!

The next twenty two pages are high-concept 'Character/Faction' blurbs. These are fully illustrated pages with small bubbles of text that in turn help emphasize or underline the themes and concepts. I can only imagine they'll be developed further in the book itself.

There are thus eleven playable character types in this game. I have no idea how it works yet, as I only skimmed the mechanics a few days ago.

With that in mind, I do want to go over each 'class' overview.

Yoroi

The giant robot class. The first two-page spread is a lavishly illustrated piece depicting a giant robot in samurai-esque armor, in a lot of ways reminding me of Gurren Lagann- more that Gurren Lagann had a lot of shared DNA with other robots and samurai motifs.

But more importantly, this is also the extremely on the nose Evangelion reference, even moreso than the one-off comic panel I excerpted above.

I will say that this particular page is… frustrating. I lack context for the decisions made to depict what it shows here. See- the Yoroi armors are magitech constructs that have to be piloted by individuals who have no karma- which is an in-setting term and does broadly follow one specific interpretation- I had read that section previously, so the short version is that when the game talks about karma, its talking about karmic ties and weight that keep you bound to the earthly cycle.

So 'No karma' means you're free to move on, while accumulating more karma makes you closer and closer to falling into a deleterious state that gets elaborated on later.

Yoroi are piloted by those without karmic bonds, I.E. naive, innocent children. Again, Evangelion inspiration is obvious here, but the decision of how to illustrate this is… Well the game was made 20 years ago. The art depicts what looks like a young teenager enmeshed in both a mechanical harness and a biological tentacle colony.

Did I mention this game was likely targeted at 15-ish year old males?

I'm not sure what I want to say about this. Do I condemn it? I kind of want to, but at the same time I am also an artist and I don't like the idea of censorship or over-policing content and expression. Could it have been done better, more elegantly? Sure.

But, it is what it is and it's what we got.

Setting that aside, the actual lore of the Yoroi armors is pretty cool- they're quite literally made of bound spirits that serve as muscles, and the pilots use magical mirrors to project themselves into the giants as a form of telepresence-manifestation. Hello there Tenno! Mirrors are also a pretty prevalent symbol in Japanese mythology and such- I myself and most familiar with them via the Amaterasu myth, again by way of Okami.

Something also that will become a trend, is that each 'splat' may have a faction or two. There is a lot of jargon and such, so the implication I got here is that proper Yoroi made by one faction is incredibly powerful but also very expensive, while the other faction that released its hold on technology and democratized it gained the ability to mass produce many more less potent tools and devices.

Thus the factions are Meikyo Yoroi (the expensive classic designs) versus the Kimen designs. There's an example of the latter in the two-page spread that looks much more obviously mechanical and utilitarian, not unlike a mobile suit.

Mentioned here also is that there is a Shinto Priesthood, in the setting of Tenra. They're near the end of this section I think.

Onmyouji

Compared to the Yoroi spread, the Onmyouji are… I don't have the same obvious connection. I make the obvious reference to Hino Rei/Sailor Mars and her iconic ofuda talisman tech, of course. And later still to the pirate clans of Outlaw Star.

The text of the spread itself mentions the daoist/taoist term, which I myself feel woefully under equipped to explore at this moment- but that's part of the fun of this essay!

In any case, we're given a lovely pinup shot of a beautiful woman in a fetchingly open kimono and peach-cream haori overcoat. This is very much Fantasy Japan styling, and I am here for it.

In terms of lore, I get the idea that the Onmoyuji are in a lot of ways writing gods into being in order to fulfil tasks. They aren't summoners, as other media and settings might imply- they are authors and editors of a magical field that pervades the setting, known as The Sha.

Quick prediction- I'm betting that there are going to be a bunch of things like The Sha, and they're either all going to be the same thing, implied or otherwise, or the game-setting will just plop down a bunch of metaphysical concepts and trust the players to figure it out.

This 'writing gods' conceit I think is all the more apt, because in the same page it points out that in the modern era, mechanical and electronic devices are becoming more and more prevalent among the taoist sorcerers, where automated abacuses and the like are used to draft and deploy Shikigami spirits.

One of the side text blurbs makes this even more obvious- with the old guard of paper-and-ink calling the new wave Shiki-slingers'. Hey there, script-kiddies!

Samurai

Spoiler alert- there are ninjas too in this game.

The introduction to Samurai is with the game's signature character- one we'll see a lot of in art throughout the game. He is a muscular, broad-shouldered man absolutely covered in red spheres, embedded into his flesh all over his body in a broadly symmetrical manner.

But of equal importance is that he is growing horns and chitin and his hair is becoming sharp and fiery.

The lore is that Samurai are essentially the Warrior Martial Sect, maybe not a culture per se yet- I haven't seen evidence, but a practice or path in pursuit of some goal. They are essentially magical… I hesitate to say cyborgs, but I do see parallels. The red gems I mentioned are refined Orichalcum, which is an amusingly common name for 'Fantasy material' in Japanese stories- it happened in Spriggan, for example. I wonder if it was a translation choice?

The Samurai essentially have chosen a life of war and battle, and are gradually becoming less human and more spirit as they add gems (each containing martial spirits bound in service), which in turn power their martial ki and inspire great transformation as they go into battle.

So the takeaway here is that the Samurai-class of TBZ are more akin to Guyver or other kinds of bio-punk Tokusatsu fare.

Also an important point is that in the text of the blurb, the Samurai know they're choosing to burn brightly but briefly, and that they can in fact drink too deep, go insane with power, or otherwise be reduced to little more than a rampaging murder-machine.

Monks

Unlike the previous three entries, the Monks are divided into three factions, and the text gives no real indication of how these characters play. Yoroi are big robots powered by angsty children, Omyouji sorcerers are well, sorcerers, and samurai are guyver-punk murderblenders.

Monks are explicitly Buddhist, and the game actuall goes into a lot more detail in the ending chapters that I skimmed already. The three factions the game presents are Ebon Mountain, Phoenix, and Bright Lotus. The most significantly powerful.

The Ebon Mountain Monks are the charismatic everyman- they're the ones engaged in the day to day lives of their fellows, or training in distant mountain retreats. The image of them is an almost Ryu-from-Street Fighter hunk of a man.

The Phoenix sect meanwhile is more obviously political and philosophically minded, and maintains a defensive force while it pursues humanitarian objectives and spiritual enlightenment. I actually want to give this blurb props for that distinction- though I have no idea how it actually plays out later in the book.

Bright Lotus is the most recently founded offshoot, and is kind of an upstart. They believe in direct charity and a simple message of salvation. I don't think it's going to end well for them.

Kijin

So the word 'Kijin' was familiar to me, and I wanted to make sure I wasn't mis-remembering it for Kirin, which is another staple of Japanese mythology.

The word Kijin is most commonly associated with a particular class of oni or similar spirit that has transcended its limits and is now akin to a god. In TBZ, Kijin refers to the deadly and unsettling cybnernetic warrior.

To reiterate, Tenra-the-setting is riven by conflict. I don't know if its under a world war against some foe or if everyone's just out against their neighbor or what, but fighting happens a lot. And as such, things that make you better at fighting and killing are probably in vogue.

The two-page spread here is a lovely kind of indulgent. Anyone who's familiar with 'gear porn' spreads of technical diagrams and the like would feel right at home here. We have an obvious cyborg who is clearly a quadruple amputee, to say nothing of whatever internal things have been adjusted- he's littered with scars and has a bionic eye. Options include but are not limited to roller-tread feet, gatling gun arms, a flintlock pistol in a robocop-esque thigh compartment, biological superhuge crab claw grafts, and more.

Oh and a pile bunker. Just, because.

In terms of tone, they feel a lot like the Samurai- this isn't a faction so much as a demographic in the extremely martial world of Tenra. There's no central political or cultural authority of Kijin. Instead, it summarizes itself with the most raw line that I would compare favorably to Eclipse Phase's taglines.

"Like pulling a long thread from a kimono, the flesh falls away and steel takes its place. That thread is your weakness."

"Keep pulling."

More seriously, Kijin are also the obvious response to wounded soldiers, which the introductory text itself declares as opportunities.

Kon Gohki

I admit I had a bit of trouble parsing this one at first- the way the page is formatted has the translation of the text aligned vertically, meaning I had to hunt for it on the page to realize what I was looking at.

Introduced in the Yoroi blurb is the concept of the meikyo mirror, which is used in a lot of magical and technological feats. It is in a very real sense kind of like a soul-medium or transfer vessel.

Koh Gohki are in fact, animated spirit-armors and warriors made not of science and programming, but the cleansed souls of Asura or warrior spirits. A soul is captured in the mirror, scrubbed clean of sin and memory, and implanted in a warframe for use as a kind of automaton-soldier or similar.

Except, this scrubbing isn't perfect, and a powerful soul can break it- thus they awaken not as they once were, but now in a cage of steel and science.

So the implication of course is that this is a playable class, that you can in fact be a 'bound spirit' of sorts in a suit of armor, distinct from the Kijin cybernetics aficionados.

Shinobi

Almost snuck up on you, didn't they!

The Shinobi are interesting, in that they're kind of a pervasive background element to the greater setting of Tenra. Just even looking at these short blurbs- and they get the most text so far out of any!

They share a decent amount of the 'spiritual back end' with Samurai, using the same basic soulgem techniques in a different way to achieve their ends- but unlike the Samurai, there's no guyver-esque body horror transformation (yet).

Also notably, is that the setting blurbs imply an almost Naruto-esque approach of ninja villages, feudal lords and fealty agreements while the ninjas undertake missions for their clients and patrons.

Oddly enough, as verbose as the Tenra ninja blurb is, there actually isn't much to say just yet. Maybe that'll change!

The ninja gal on the splash image though is hella cute though!

Kugutsu

This one also threw me for a loop, in terms of layout and formatting. Due to hwo the page is set up, I thought the left hand page was the introductory paragraph, which continued on the right. In fact it was an in-setting message to a client about receipt of a product.

The product was the Kugutsu doll August Moon.

As the text describes, Kugutsu means 'Mannequin', a doll or statue carved from a tree, and then animated by magic. They are essentially living art and homunculi in one, and beauty is significant component to their writeup.

I am already seeing the idea that in a multi-class game, Kugutsu PCs are the 'face' or 'social' characters.

They are apparently so beautiful and rare that whole city-states go to war over the privledge of marrying one- to say nothing of how unmistakably uncomfortable the concept is- these doll-people are products, and the text says people treat them like such.

Except, the Kugutsu are so well made, they functionally are human. They question their own existence, they lament their circumstances, they- as the text itself says, suffer.

Mushi-Tsukai

If you don't like bugs, avoid the Annelidists!

A trope in Japanese myth and fiction, is the symbolic use of centipedes and similar creatures. I'd likely seen it here and there incidentally, but my first real up-front experience with it was FromSoftware's Sekiro. Minor spoilers, but they lean on that image and symbolism heavily in its examination of immortality.

In Tenra, Annelidists are kind of entymologist-mages that travel the world looking for new and exotic spiritual bugs to collect, and host in their own bodies as part of a power-up scheme. They are avowed healers and sages… and most folks rightly find them kind of creepy because you have bugs living in your body what the hell man!?

The Annelidsts very much are a kind of 'Heroic' body horror conceit that I think has become somewhat in vogue over the past couple decades. They're icky gross powers, but the people who use them are just regular people, if not ostensibly good.

Oni

So Tenra decides to do something pretty interesting here. Not necessarily novel or stunning, but it I still find it worth mentioning. Oni in Tenra are the 'native species' of the world (planet? I'm not sure yet. Remember, we haven't actually gotten to the setting chapters yet, these are literally the first 30 pages of art and character spreads.)

The text clearly says that the Oni are characterized as violent kidnappers who eat regular folk alive. This is also a blatant lie maintained by the factions that prey upon and want to remove the Oni from the world.

Instead, the Oni are essentially the 'communal psychic race', their horns are antennae that they use to connect to each other across The Sha field. (Hey I was wrong, so far they're just sticking to one!)

But, also of horrifying note is that Oni parts are in some ways crucial to the magical technology the other factions use- Yoroi armor and Kon Ghoki warriors are powered by harvested Oni hearts contained in technological vessels. Most humans have no idea.

The Oni are at a glance depicted as humble, noble or just people, and in a funny sense I want to equate them to both the Protoss of Star Craft ,and classical elves. Also interestingly the choice of clothing is… Well one Oni is wearing almost nothing, showing off long legs and all kinds of body art- the other Oni on the character spread is wearing something that looks familiar but I can't really place what culture or region its from. It's definitely not like 'classic' Japanese though. More middle-east?

Agent

The last 'splat type' is called Agent, but what they really are, are Shinto Priests.

From prior skimming, I had some ideas of what the shinto priests are like in TBZ, but this introductory blurb focuses primarily on their role as the leading political actors in the setting. They are the hidden manipulators that guide the flow of civilization. They play all sides, offering gifts and insights to lords and kings, to achieve their own ends.

But, what the text makes abundantly clear is that the priesthood are not bloodless masterminds- the cycle of war and death that even now thirty two pages in, is most assuredly laid in great part at their feet. Is it for a good reason? I don't know, maybe the book will tell me later on.

This also as a class entry isn't telling me much of How they do things- I don't see their spells or methods. The main cultural takeaway on this page, is that as a priest achieves high rank, they wear a mask and have all records of their identity purged.

Whew. Having done all that, I think I'm going to end this Essay here for now and pick it up later!

[Before the Collapse]

[Before the Collapse]